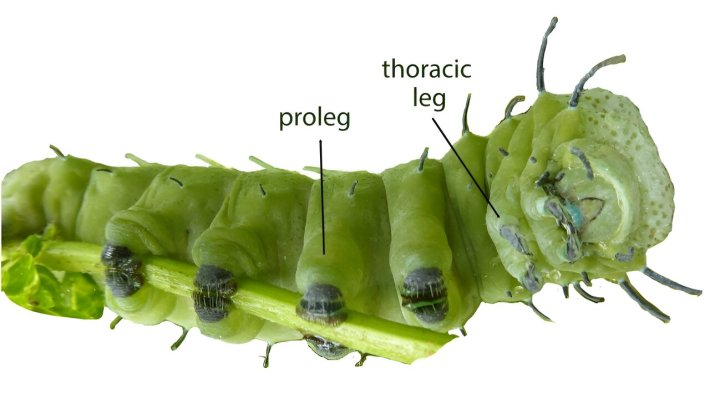

Earlier this month, a paper came out in the journal Science Advances explaining how caterpillars acquired their "chubby legs," a description that, on first glance, felt rather judgy. A caterpillar's entire purpose is to eat all it can as fast as it can and grow as big as possible. Of course the many legs sprouting from its chubby body will also be chubby! But as I read more about the paper, I realized a key distinction. The chubby, stump-like legs that help a caterpillar inch along leaves and stems are not actually legs at all. They are fake legs also known as "prolegs"—stumpy nubs of flesh that allow the caterpillar to move around.

A caterpillar's real legs, the ones that will morph into its final adult legs as a moth or butterfly, aren't even used for walking. These three pairs of legs, called the thoracic legs, are all clustered by the caterpillar's face. In fact, a caterpillar is fully able to inch around with ease even if all six of its "real" legs have been removed or immobilized, raising the perennial philosophical question: Should a leg be defined by anatomy or function? Is a fake leg capable of walking, lifting, and gripping any less "real" than the so-called "true" legs used for none of those things? What is realness for a leg?

If you already knew about the great caterpillar leg scam, I applaud your wisdom and knowledge. In hindsight, perhaps I should not have been so surprised. Adult insects generally have three pairs of legs, so it would seem strange for a juvenile insect to have, say, 20-plus legs and then simply discard most of them as they grow up. And the caterpillar on the cover of the seminal text by which many of us are introduced to this larva, Eric Carle's The Very Hungry Caterpillar, is scientifically accurate in that it has six legs (two are located at the back of the caterpillar's body, which is less accurate; these are called anal prolegs and are also fraudulent).

This leg-based revelation is also unsurprising in the grand scheme of arthropods, a phylum named for their jointed legs. If there's one thing I can expect from an arthropod, it's a surprising evolutionary repurposing of a leg. The insects known as water boatmen turned their legs into paddles; dung beetles turned their legs into scythes and spurs to slice dung into balls and roll the balls back home; the venom-injecting fangs of house centipedes are actually highly modified legs, and their back legs are long enough to rival their actual antennae. But the caterpillars' leg scheme, representing not the modification of an anatomical leg but the evolution of a fleshy appendage that looks like a leg, walks like a leg, and in polite society would pass easily as an ordinary, run-of-the-mill leg, was very surprising to me.

So how does a caterpillar get its fake legs? (I will not be using "proleg" because it is too close to "prolapse.") Scientists were unsure if the fake legs were actually just another kind of modified real leg, if they were modified lobes of real legs, or something entirely new. The new paper proposes the fake legs are not at all related to real legs. Instead, some of the genes expressed in the caterpillar's chubby fake legs were actually responsible for the legs of crustaceans.

Unlike us bony humans, caterpillars can't move their fake legs independently to stride forward. Instead, they use their fake legs like anchors to clutch to whatever surface they're inching along. To move forward, the caterpillars detach their fake legs from back to front and hold them aloft as they contract their muscles, lurch their body forward, and then lower their fake legs to anchor them once again. The tip of every caterpillar's fake leg is a little barbed pad called a crochet, which works like velcro to fasten the crochets to a leaf, a twig, and any other substrate a caterpillar deigns to walk upon. Who needs feet when you've got sticky stubs!

Perhaps realness, at least genetically speaking, is of no import to legs of this kind. Legs, philosophically speaking, do not need to be permanent. Just look at frogs! Some appendages are evanescent, appearing in flashes of youth to help hungry hungry caterpillars find their next meal. So the next time you encounter a caterpillar, revel in the fact that you are seeing the most fleeting kind of legs, stubby stompers that will soon exist only in the realm of memory, so treasure them while you can.