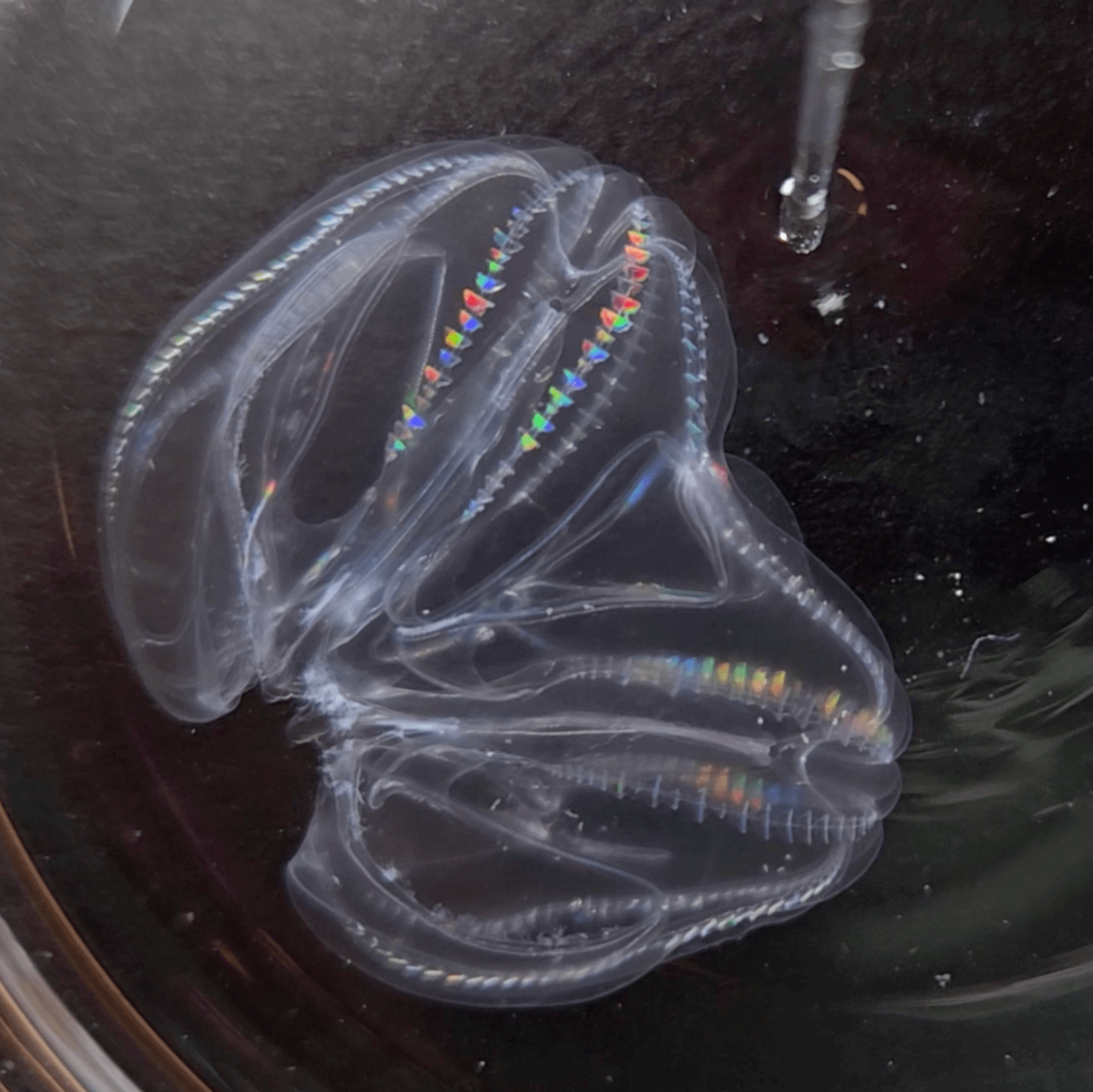

One morning, Kei Jokura was inspecting his tankful of ctenophores—gelatinous, shimmering sea creatures approximately the size of apricots—when he noticed one had, seemingly overnight, gained a second rear end. As such, he was overcome with excitement. "I have to show everyone," he remembers thinking.

At a glance, the bodies of ctenophores, which are also called comb jellies, are shaped simply, like ovals. They have a mouth at one end and a concentrated sensory system called an apical organ at their rear. The small region of the apical organ contains "a photoreceptor or gravity receptor and some pressure receptor or chemical receptor," said Jokura, who is a ctenophore biologist at the National Institutes of Natural Sciences in Okazaki, Japan.

But this particular comb jelly had two mouths, two back ends, and two of these sensory apical organs. It was not born this way, but rather was the result of two different comb jellies fusing, seamlessly, into one individual. Jokura and colleagues describe this discovery in a new paper published today in Cell Biology.

Joan J. Soto-Angel, a marine biologist at the University of Bergen in Norway who was not involved with the research, has observed some M. leidyi individuals with two apical organs in his own research. "My first thought was an aberrant regeneration," he wrote in an email. "But the author’s findings show that it could actually be derived from two animals fused, which I find fascinating."

Originally, Jokura was investigating how Mnemiopsis leidyi ctenophores, which are also called warty comb jellies, respond to gravity. He collected comb jellies in the summer off the piers of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass. The creatures are too fragile to be caught with a net, so the researchers affixed a plastic scoop to the end of a long stick and ladled the invertebrates out of the water and into an orange Home Depot bucket.

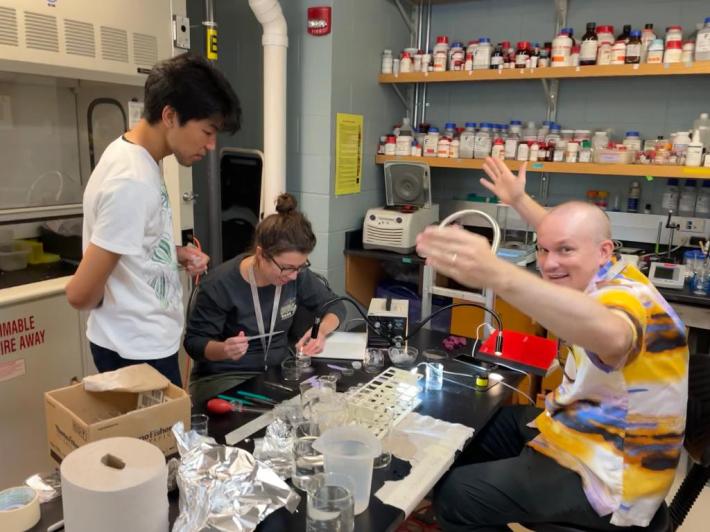

When Jokura showed the strange, double-ended comb jelly to his colleagues, some were confused. "At first I was surprised because I thought that they were just two comb jellies that had gotten entangled," said Mariana Rodriguez-Santiago, a neurobiologist at Colorado State University and an author on the paper. But when Rodriguez-Santiago poked at one end of the comb jelly with a syringe, the entire body reacted, revealing the comb jelly was responding as one organism. "It didn't take long for me to realize that took two comb jellies had fused," Jokura said.

Jokura had never encountered or even heard of a fused comb jelly before. But he came across a paper from 1937, in which a scientist named B. R. Coonfield had conducted a series of grafting experiments on the ctenophore. "He focused more on orientation" and the effects grafting had on different parts of the body, Jokura said.

The authors of the new paper put their heads together on experiments with several different cutting locations to see if they could fuse more comb jellies together. "We found that if you cut them in full half, they just die," Rodriguez-Santiago said. "But if you just cut a subsection of the lobe, then they can fuse." The researchers would pin the two cut comb jellies together on a dissection dish overnight, and nine out of 10 of these experiments resulted in a fused comb jelly with no visible scar.

In the first hour of fusion, the newly joined lobes would relax and contract spontaneously. But within two hours, 95 percent of the comb jelly's movements were completely synchronized. And all of the fused comb jellies reacted the same way to poking; a jab at one side of their body resulted in a full-body startle response, suggesting the two animals had managed to merge their nervous systems. "How fast it happened, for me is the most surprising thing," Rodriguez-Santiago said.

But the fused comb jellies remained individuals in one crucial way. When ctenophores eat, tiny hairs called cilia in their digestive canal help waft their food through the gut and toward their anus. But M. leidyi comb jellies have what's known as a transient anus, a pore that appears when needed and vanishing soon after. "Oh, let's go to poop. Oh, let's close," Jokura explained. The fused comb jelly's two anuses were fittingly fickle, excreting not in sync but rather on their own unique schedules. So theoretically, at any given moment, a fused comb jelly might have had two anuses, one anus, or no anuses at all.

But after the researchers ran feeding experiments on three fused comb jellies, they noticed something even stranger: The side that ate the food was not the side responsible for expelling what remained. "One half ate it, and the other half pooped it," Rodriguez-Santiago said, adding that she has no idea why this happens.

The comb jelly's ability to fuse nearly entirely with another of its species suggests the species may lack a tool for allorecognition, meaning it is unable to distinguish between itself and others. Some colonial animals, such as hydrozoans in the genus Ectopleura, can fuse one colony into another, creating a viable colony of multiple genetically different individuals, Soto-Angel said. But "Mnemiopsis leidyi is even more surprising, given that there is a component of movement and coordination involved," he added.

But the fact that comb jellies are free-living and not bound to a colony means they do not spend time in very close contact with others of their species. As such, accidentally merging into a neighbor is not an everyday occurrence. The researchers suggest that the ability to distinguish between one's self and others only emerged later in animal evolution. These comb jelly have neurons that can connect without synapses, and Jokura hopes to conduct follow-up experiments using fluorescent dye to track "how they coordinate their neuronal activity," he said.

The researchers kept all their fused comb jellies alive and healthy in the lab for three weeks. But comb jellies can live for about a year, so they released their double-ended experiments back into the waters off the pier, where they nobly lived out their lives, eating and eating and pooping and pooping.