This week, The New York Times is publishing a big list of the top 100 books of the 21st century. It is a little strange to do this in 2024 instead of 2025 at a nice even quarter century, but that's fine, maybe Trump will make reading anything but The Art of the Deal illegal next year anyways. The list is being released a little at a time, to build up excitement. Twenty more books are revealed each day this week. By Friday, all top 100 books will be published. As of publication, only 60 of the books have been announced. The books were chosen based on top 10 lists submitted by "503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review." Five hundred and three seems like too many to me, but what do I know?

There are plenty of problems with the list, as there are with every list ever made. It is very Anglo. So far, only a handful of books in translation appear, and of those, two are by Elena Ferrante: Days of Abandonment and The Story of the Lost Child. I like Elena Ferrante fine, but it seems very unlikely to me that any author would have written two of the top 100 books of the century. There is almost no genre fiction included yet, and no poetry. But in reading the list, there was something else that irked me, that itched just under the surface.

It is not a new or controversial take to dislike a ranked list of culture made by a news organization. Every list is fake. Book lists—like their cousin, album lists—are built to stir up engagement. People will click on the list. People will talk about the list. People will write blogs like this about this list. If Jonathan Franzen's Freedom is crowned the best book of the 21st century, women in dresses they will excitedly tell you "have pockets!" like it's novel will storm the Times building. This is the kind of response the paper wants. Engagement, after all, is money.

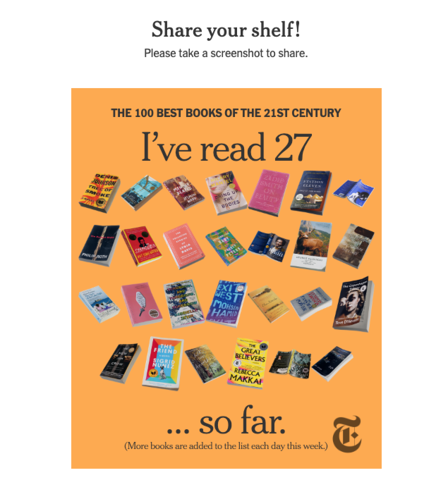

What is kind of new is how blatantly The New York Times is making a play for that kind of engagement. The list features two checkbox options beneath each book: "I've read it" or "I want to read it." These are the only options, as you must want to read these universally beloved books! Once you've checked all your truths, the end of the list presents you with a beautiful shareable graphic that using some algorithm adds the covers of the books you've read.

Here's what mine looked like on Tuesday:

It's no secret that the revenue engine of the Times is Cooking and Games, and it seems the Books section has, either wisely or crassly, taken a lesson from the success of Wordle: people like to brag about their score. Increasingly, on GoodReads and TikTok and elsewhere, reading is understood as a quantifiable endeavor. The more books, the better! Consumption is the only thing that matters.

Plus, in many ways, this is The New York Times ranking New York Times bestsellers that have been reviewed in The New York Times. The one interesting exception that sort of proves the rule is Torrey Peters's Detransition, Baby, a book I really liked. While I was happy to see it on this list, there's something almost revisionist about its inclusion.

"I’m really grateful to all the readers over the past few years for making this happen. [Detransition, Baby] came out when Pamela Paul was head of NYTimes books—and D,B wasn’t even initially reviewed there(later got capsule review when it was nominated for women’s prize). It’s heartening to see that a major corporation/institution can come to recognize a work of art—due to readership and care—even despite that institutions own initial disinterest," Peters wrote on Instagram.

Detransition, Baby was a highly celebrated book. It sold well. It was nominated for awards. Of course it would be added to this list. It's good, in my opinion. But the thing these lists completely erase is the reality that art can only be good subjectively. There is no objective good.

And yet, book culture wants there to be. Book culture in America right now, such as it exists, wants everyone reading the same books, talking about the same books, agreeing that these books are uniformly and undeniably good. And what it leads us to is an abundance of lists and recommendations that are all identical and not interested at all in the goals of literature. It reminds me of this tweet I saw last week that I found very funny:

ohhhh my god you’re an independent bookstore? and your staff recommendations are ocean vuong and elif batuman? should we throw a party? should we invite otessa moshfegh?

— elizabeth handgun (@OneFeIISwoop) June 24, 2024

The list shows a similar problem to the book recommendation cards: all the recommendations now are the same. There is not one book on the Top 100 list so far that I have not seen on dozens of lists before. So then, who is the audience for this list if not people who read a lot? What is its goal? Because it certainly feels like the goal isn't to sell books or to even endorse great books, but to codify a kind of public opinion that already feels fully solidified already.