BERLIN — Tareq Alaows had been on the run for two months and had just arrived at Dortmund’s central train station when he felt, for the first time in his journey, intense, unmistakable hunger.

He had traveled from Damascus to Vienna, some of the way on foot, some of the way on rickety dinghies, before finally boarding a train to Dortmund. That entire time, he had forced himself to eat and drink merely to stay alive. Eating had been a task; refueling. But as he got off the train in Dortmund, he suddenly realized he was hungry. He was struck by a craving for something delicious, hot—a desire that went beyond mere necessity and instead called out for pleasure. He found the only place at the station still open: a KFC.

"That was the first time that I felt hungry,” Alaows remembers, “and it was a signal to me that I was safe."

It's been almost seven years since Alaows stepped off the train in Germany, ate his fried chicken, and then found a police officer to declare he was seeking asylum. A lot has happened since then. The 31-year-old has settled nicely into Berlin life. When we meet outdoors at a bar overlooking the busy Kottbusser Tor junction in Kreuzberg, he seems to be a familiar presence in the neighborhood. During our conversation, a stranger comes up to us and begins speaking to Alaows in Arabic. Later, he tells me that the man had asked him for help, saying that he had been kicked out of his temporary shelter and needed a place to go. Alaows had given him his contact information and promised to help him out. I ask him if this happens often. “All the time," he says.

Helping out others has always been non-negotiable for Alaows. Before leaving his home, he worked with the Red Crescent, the sister organization of the Red Cross, while documenting human rights abuses in Syria.

"I grew up in a politically active family. My father was a political journalist, and we spoke about a lot of political topics, and about the regime," he says, referring to the al-Assad governments that have ruled Syria for 51 years. "Obviously none of this was officially allowed, and my parents always made it clear that we could only speak of these things in private."

Alaows studied law in Aleppo, with a focus on human rights. The irony was not lost on him. "It was crazy. I could envision human rights in theory, but in practice you couldn't even say the words 'human rights' on the streets," he says. "It really made me not want to continue my studies at some point, because I couldn't see a purpose.”

He appears to have found that purpose in helping others reach safety. He's become an active member of the Green Party, running for the Bundestag before withdrawing amid racist threats, and he’s worked with organizations such as the Flüchtlingsrat Berlin (Refugee Council Berlin) and Leave No One Behind, a movement dedicated to raising awareness of discriminatory, anti-refugee actions at the EU's borders. Right now, his time is spent trying to help non-white refugees from Ukraine find safe passage while calling attention to the unequal character of the EU's policies toward non-white refugees from other conflicts.

"I saw the images from Ukraine,” Alaows says, “and the first thing that went through my head was ‘Syria.’ It was the same pattern, and the same Russian claims that they were only attacking military structures. But the reality is that they were attacking civilians in apartment buildings, in the cities. That's what they're doing in Ukraine now."

Syrians and Ukrainians don't simply share a universal experience of displacement; both of their countries have been laid waste to by Vladimir Putin's bombs, entire cities razed to the ground by Russian artillery. The Syrian civil war started in 2011, but it was Russia’s 2015 escalation that ignited a mass exodus, mostly into neighboring countries, but also to Europe. According to data from the European Union, 362,800 Syrians applied for asylum in EU member states in 2015, with about 158,700 of those in Germany.

While about 6.6 million Syrians have been forcefully displaced from their country since the start of the civil war, the situation in Ukraine is escalating at a much quicker pace. As of April 10, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that more than 4.5 million people have fled the war in Ukraine. In just a matter of weeks, over 300,000 Ukrainian refugees have arrived in Germany. When the Russian army invaded its neighbor on February 24, it ignited Europe's largest movement of refugees since World War II.

In response to the flood of humanity, the European Union took a rather unusual step: It quickly decided on a joint refugee policy which would give refugees from Ukraine, including those of other nationalities who were residing in Ukraine, a special protection status. What this means in practice is that refugees from Ukraine have the right to seek refuge in any EU member state and stay there for a year, with the possibility to extend that stay up to three years. The long-winded asylum application process which is usually the standard for refugees coming to the EU has been waived in favor of a quick, uncomplicated process in which arrivals receive immediate work permits and can move freely to stay with friends or family in the country, if they choose.

"We're currently seeing a 180-degree turn in Europe's refugee policy in a way that was unimaginable over a month ago," says Wiebke Judith, a legal policy advisor at ProAsyl, a German advocacy organization for refugee rights. The liberties granted by the special protection status, she notes, “make it possible to integrate much faster, and it makes it possible to be much more independent."

Under the previously standard practice, asylum applicants had to live with other refugees in so-called “initial reception facilities” while their application was processed, regardless of whether or not they have family they could stay with instead. When Alaows arrived, he was placed in one of these, located in the middle of nowhere.

"I was in a facility in the middle of a forest. In order to buy tobacco, I had to walk 10 kilometers just to find the closest supermarket," he remembers. "This was the strategy of the former government, to just completely isolate people. So even if these people had the right to work, how were they supposed to get to their place of employment if they're in the middle of the forest?"

Alaows began learning German and using Google Translate to study German asylum law, in order to advocate for better conditions for himself and for his fellow refugees, going so far as to camp out with other asylum applicants in front of the mayor's office in the city of Bochum for 17 days after the city tried to permanently house applicants in an indoor gymnasium. There were, he remembers, few opportunities for Syrian refugees to speak for themselves and advocate for their own interests. There was a lot of talk about refugees, but no one was actually letting them have a say in their future.

The war in Ukraine has galvanized a mass volunteer movement, and many former Syrian refugees who are settled in Germany have undergone a role-reversal of sorts, with them providing the support and aid that they themselves received—while witnessing the sort of policy changes they had sought years ago.

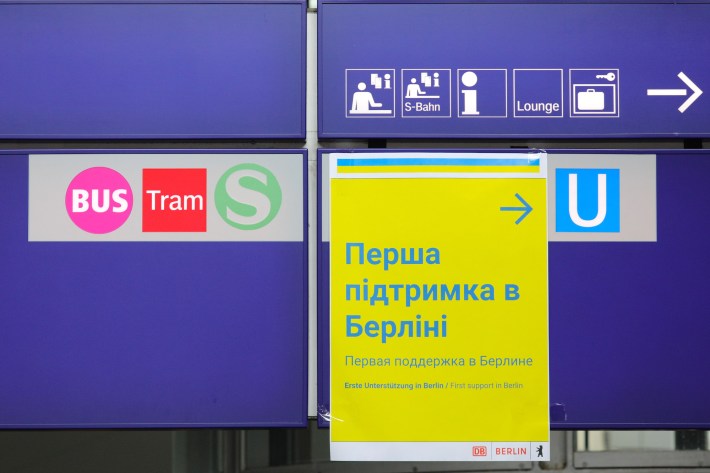

Refugees from Ukraine arriving in Berlin have a couple of options: If they're arriving by train at the city's central station, they have the option to travel on to other destinations in Germany, free of charge. For those who perhaps don't have friends or family members, buses are available to take them to shelters across the country. According to a survey conducted by the Federal Ministry of the Interior, 42 percent of refugees from Ukraine entering Germany are choosing to stay in large cities, with the majority settling in Berlin. For those who wish to stay in Berlin and claim asylum here, their first destination may be the arrival center for asylum seekers in Reinickendorf, north of Berlin. This is where Ibrahim Youssef has been spending a lot of his free time as a volunteer.

Youssef wears a highlighter-yellow vest to indicate he's a volunteer. A piece of tape is stuck on his chest, displaying his name and the languages he speaks (English, German, Arabic). He points to other volunteers wearing bright orange vests. "Those are the ones who can speak Russian or Ukrainian,” he tells me.

Youssef is 30 years old and has a bright smile with which he greets fellow volunteers and arrivals alike, because he’s been both. He arrived in 2018 and has been studying for his master’s degree in molecular biology at Potsdam University. He’s originally from Qamishli, in northeastern Syria, and is part of the country's Kurdish minority. He had to travel across Iraq, Turkey, and Greece, mostly on foot, before he finally reached Germany.

"When I got to Germany, there were people here waiting for me, helping me, like we are doing now for the Ukrainian people," Youssef explains. "So I thought it was my duty to do something, to give what I got to the other people to help them.”

It's lunchtime at the arrival center in Reinickendorf, and the weather is unusually warm for Germany in March, so people are sitting outside at picnic tables, with plastic bottles of water and slices of pizza on paper plates. Everyone who isn't wearing a volunteer vest looks exhausted. Youssef says he tries to keep things upbeat while interacting with newcomers. The people who come here are traumatized and many still have family members in the war zones, he explains. The focus is on talking about next steps, not looking back.

"We are trying to tell them everything is fine," Youssef says. "I tell them, ‘I am also a refugee here. And I am working, I am learning German, I am volunteering, I am studying. It will be fine for you too.’ I hope it helps a bit."

Majd Kurabi has also been helping out at the arrival center since the start of the Russian invasion. "What the Russians did in Aleppo was a disaster,” he says. "So when we heard that Russia is preparing [to attack] Ukraine, my heart started beating so hard. I know the terror that would come, I know the horror that they would see."

The 29-year-old Aleppo native, who I spoke to by phone, told me he’s been struggling to find the right words to say to new arrivals. Like Youssef, he tries to keep things positive. "I tell them, ‘Don't worry. Everything would be OK. I was exactly like you six years ago. It will get better. Right now, you are in the worst point, but it will get better.’

"But I cannot comfort them in the way that they need,” Kurabi admits. “Because when I'm speaking with them, I feel that they're afraid. They are thinking about Ukraine and that it will become another Syria, a war for 10 years, 11 years. And the people will have to run away to build their life from zero. I try to comfort them with my story. But in the end I feel the sadness.”

Volunteers and administrators are preparing to move Ukrainian refugees to a newly established shelter in Berlin’s former main airport in Tegel. But for many refugees, the arrival center in Reinickendorf is still an important source of help and information. Svetlana, from Zhytomyr Oblast, arrived at one in the morning with her two children (ages 8 and 4), her mother-in-law, her sister-in-law, and two female cousins. They were here to get registered, get warm, rest, and then keep moving.

"We have no relatives or friends here where we could stay, so we will continue our journey," she says through an interpreter, as her youngest child pulls at her sleeve. People in situations like Svetlana’s—those who have nowhere to go—will be housed in shelters all across Germany.

Close by, Lyudmila is sitting in the sun with her 9-year-old daughter and her 18-year old niece, Anastasia. They came from Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. "The journey was very difficult. We traveled for two days," Lyudmila says, before looking away. "I don't really want to think about it."

Although they're safe here, the trauma of the past weeks is hard to shake. "I still feel like I'm there," says Anastasia, who was in the midst of her apprenticeship as a pastry chef in the city of Kryvyi Rih when she fled. "Sometimes I'll hear a sound and think it's an air raid siren, and that something is about to happen."

Three of Lyudmila's four children are still in Ukraine. Her oldest son is fighting against the Russian army; she doesn’t know where he is right now. Her two other children are university students in Kyiv.

Lyudmila hopes to stay in Germany. "My daughter's future is not in Ukraine anymore," she says, absentmindedly putting her hand on her youngest child’s shoulder. "Because even if the war ends, no one knows how things are going to continue. Perhaps Ukraine will not even exist at the end of all this."

According to the Ukrainian government, the country hosted just under 80,000 international students at its universities in 2020. Murat and Gulchat, who I met at Reinickendorf, are both from Turkmenistan, and were studying in Kyiv to become teachers when they decided to leave the country.

"It's war, anything can happen," Murat says. "There is war, the train was stopping a lot and people were scared. We were on the road for 18 hours until we arrived to Poland.” Despite the dire situation on the ground, both he and Gulchat say that they want to return to Ukraine and continue their studies as soon as possible.

While Murat and Gulchat were able to leave Kyiv without major incident, thousands of students from African, Asian, and Middle Eastern countries have faced considerably harsher treatment. Many have found themselves stuck at borders, turned away from evacuation trains, and illegally placed in detention facilities. They face this treatment despite the fact that the EU has issued a visa-free travel permit for anyone who had legal residency in Ukraine, regardless of nationality.

"This is an unlawful action from the EU," Alaows says. "This is once again a racist division of people that is being carried out. They are actively denying these people their legal rights."

In Berlin, organizations such as Each One Teach One, the Tubman Network, and Leave No One Behind have been advocating for non-white refugees coming from Ukraine, but everyone still hears the horror stories.

Majd Kurabi tells me of his friend Samar, who has Syrian ancestry but lives in Kharkiv and has a Ukrainian passport. According to Kurabi, Samar was trying to cross into Poland from Lviv and was told by border guards that she couldn't pass into the country. "Imagine that. She is a Christian girl, but her name is a Muslim Arab name. They told her, ‘Sorry, you cannot enter.’ She said, ‘How I cannot enter? I'm running from bombings!’"

According to Kurabi, Samar had to find an alternate route to safety and ended up in Slovakia, where she's still located, before—she hopes—moving on to Germany. "All of this, just because of the name. So this is racism, yes, definitely. This is racism."

"Certainly various factors play a role in this,” says Wiebke Judith, “but of course one part is the racist structures of our refugee and visa policy, which means that [people from] certain countries more easily receive visas or can travel without one, while people from countries where there is a greater threat of persecution or war often have less access. This means that these people are forced into irregular escape routes."

It is worth detailing what one of these "irregular escape routes" looks like. Here is Kurabi’s story: He and his younger brother made the decision to leave after fighting intensified in both their university town of Idlib and hometown of Aleppo. But his parents couldn't join them. Their jobs—his father is a doctor at a hospital and his mother is a professor in a civil engineering facility—meant the regime wouldn’t renew their passports in order to stop them from legally leaving the country. The plan was that the brothers would leave while Kurabi's brother was still under age 18, so that it would be easier to justify evacuating his parents later, once they had found asylum. But things didn't work out as planned.

The brothers crossed into Lebanon, and boarded a plane to Izmir, Turkey. From there they considered a smuggler's car, but the price of passage was too expensive. The cheapest option ended up being a boat that would take them across the Aegean Sea to Greece. The boat capsized. People drowned.

"I couldn't help people," Kurabi says. "I was helping my brother. You know, swimming in the sea is very hard. You assume that, you know, you know how to swim. That it's not that far. But the waves kill you."

They survived, and got back on another boat, and made it to Greece. Like all Syrian refugees at the time, they were entitled to free passage across Greece. But local authorities on the island of Mykonos, where Kurabi landed, were overwhelmed, and gave him papers explaining how he could obtain his passage permit, instead of giving him the actual permit. The papers were in Greek. Kurabi had no idea what to do.

Kurabi managed to get his brother on a plane, but got spooked when there seemed to be a problem with his passport and ran away from the airport. Two days later, he tried to get on another plane. Two Afghan girls in the check-in queue in front of him had fake Chinese passports. They were arrested, and Kurabi was taken with them under suspicion of being an Albanian smuggler. “They wouldn’t even look at my papers,” he says. “I gave them my Syrian passport, and they said, ‘Where is your Albanian passport?’”

The border authorities eventually accepted his passport as legitimate, but fingerprinted and detained him anyway. Kurabi remembers the majority of detainees being refugees from Albania who had been incarcerated for months. “People were telling me, ‘We have been here for three months, we have been here for six months,’ and I started to panic.”

Eleven days later, he was released. “They told me, you are the luckiest person ever in the Earth, to only get 11 days.”

Eventually, he made it to Berlin. He says he is one of the lucky ones.

"What you're hearing right now is the story of a tourist,” he tells me. “Not even a refugee. I didn't tell you about the people who went walking. I didn't tell you about the people who froze to death in the forest, because the smugglers took their money, their clothes, everything, and left them to die. So I'm telling you, all this horror you heard from my story, as a refugee, still, I was a tourist."

While the invasion of Ukraine has prompted an outpouring of solidarity and support from the EU, it has also brought to the fore an ugly contradiction: that even something as morally simple as providing aid to people fleeing a war is still situated within a system of racial hierarchy.

Kurabi and Youssef were keen to point out that the worst incidents of discrimination they’d heard of were from along the borders of Eastern Europe. Poland's policy of welcoming Ukrainian refugees with rather open arms—the country has received more than 2 million Ukrainian refugees so far—feels particularly unsettling when contrasted with the situation at the Polish-Belarusian border. At the same moment the Polish state is welcoming in white Ukrainian refugees at one of its borders, brown people are, at this very moment, dying from cold and hunger at another.

Polish human rights activist Aleksandra Chrzanowska was quoted by the Polish radio station TOK FM on the unequal treatment between Ukrainian and non-Ukrainian refugees: "Unfortunately, the situation on the Polish-Belarusian border looks completely different from a few hundred kilometers away," she told the station. "Refugees are not welcome here; on the contrary, they are caught by border guards and the army and pushed back. Even if they're in poor health, they are forced back to Belarus, where they face torture."

Even those who have successfully settled in Germany say the welcome mat rolled out for Ukrainians can make them feel unwanted. In early March, refugees from countries such as Syria and Afghanistan were suddenly ordered to leave their temporary homes in Reinickendorf and move to ones further away—Ukrainians were going to need their spots. Entire families who had been living in Reinickendorf for months or even years, with their children enrolled in nearby kindergartens, had to pack up and leave in a matter of days.

On the German talk show Hart aber Fair (Hard but Fair), guests spoke of Ukrainian refugees being "from our cultural circle," while others pointed out that a majority of Ukrainian refugees consist of women and children, while many who came and continue to come from Syria and other non-European countries are men. In the same episode, there was a reference to "cowardly men of eligible fighting age," suggesting that Syrian men were running away instead of defending their country. Never mind that men above the age of 18 currently cannot leave Ukraine.

These kinds of comparisons obfuscate the uniqueness of the situation in Ukraine. "It has to be said that the escape route [for Ukrainians] is thankfully less dangerous than the kinds of escape routes we usually see," says Wiebke Judith, referring to the notorious "Balkan route" and dangerous boat rides on the Aegean that many refugees, including Alaows, Kurabi, and Youssef have had to endure. "So far, there have been no report of deaths at the borders. And that's really good.

"Unfortunately, that's not the usual situation. Since many of these people don't have a way to legally enter, they have to embark on really dangerous escape routes. They're going across the Mediterranean, across the Aegean, across borders where they are beaten back. So that is actually still the reality at most external European borders. This means that we have a situation where families decide that perhaps the husband or brother will set off on this dangerous journey in the hope of later being able to bring the mother and children [more safely]. Or because Syrian men, for example, do not want to participate in the war crimes committed by Assad's army."

Nonetheless, politicians continue to draw comparisons between the different groups of refugees. Franziska Giffey, Berlin's mayor and the former government's Minister for Family Affairs, was criticized for implying that Ukrainian refugees were more willing to work than other refugees. "We hear from the Ukrainian community that many who arrive here don't first ask: Where can I apply for benefits?" she said. Although she has since walked back her statement, the original implication left a mark.

For people like Alaows, this kind of comparison is a slap in the face. "The situation for Ukrainians is completely different,” he says. “A legal framework was created for them so that they could work immediately. I've been advising people for years. You have no idea how many people aren't allowed to work, and how many people haven't received work permits for years. There are people who have never been allowed to legally work in Germany."

It’s not that Ukrainian refugees should not receive these liberties, refugee advocates are quick to make clear, but that all refugees could and should have been treated the way they are. No one should have to risk drowning, human trafficking, or being turned around at the border just to escape violence. Nobody should be forced into an “irregular escape route.”

"The situation in Ukraine has shown that a different kind of asylum and migration policy is possible," Alaows says. "I see how the fortress that is Europe has opened a door. My hope is that, through this wave of solidarity, we can open many more doors.”