Welcome to Margin of Error, a politics column from Tom Scocca, editor of the Indignity newsletter, examining the apocalyptic politics and coverage of Campaign 2024.

On Thursday, the New York Times and Siena College released their first new presidential poll since Kamala Harris replaced Joe Biden as the presumptive Democratic nominee. After days of exuberant coconut-tree memes and a flood of fundraising, Harris was narrowly trailing Donald Trump among likely voters, 48 percent to 47 percent, within the margin of error. One way of describing it was to say that Harris had erased most of Biden's accumulated deficit; another way was to say that the race had returned to more or less where it was before the crisis began.

So far, the campaign polling has been the least exciting part of the story of the 2024 election. Tomorrow, it will have been a full month since the Biden–Trump debate—a month of the highest possible narrative drama, culminating in Biden's unprecedented decision to drop out. But the polling was persistently less feverish than the news. While professional political observers were convinced within the first five minutes of the debate that Biden was ruined, the poll-answering public reacted more slowly. The campaign crisis manifested itself not as a sudden collapse but as a slow deflation of Biden's standing from week to week. As panicked commenters and Democrats warned of a coming Trump landslide, what seemed to be developing instead was an ever greater number of ways that Trump might collect a modest victory.

Meanwhile, on the Trump side, a weekend of shouting about how the attempt on his life had made him a certain winner—how the public couldn't resist the image of him clambering to his feet, bloodied, waving his fist—led to no discernable polling surge. Nor did his Republican National Convention generate a convention bounce. Trump is Trump, and everyone already has a settled opinion about him.

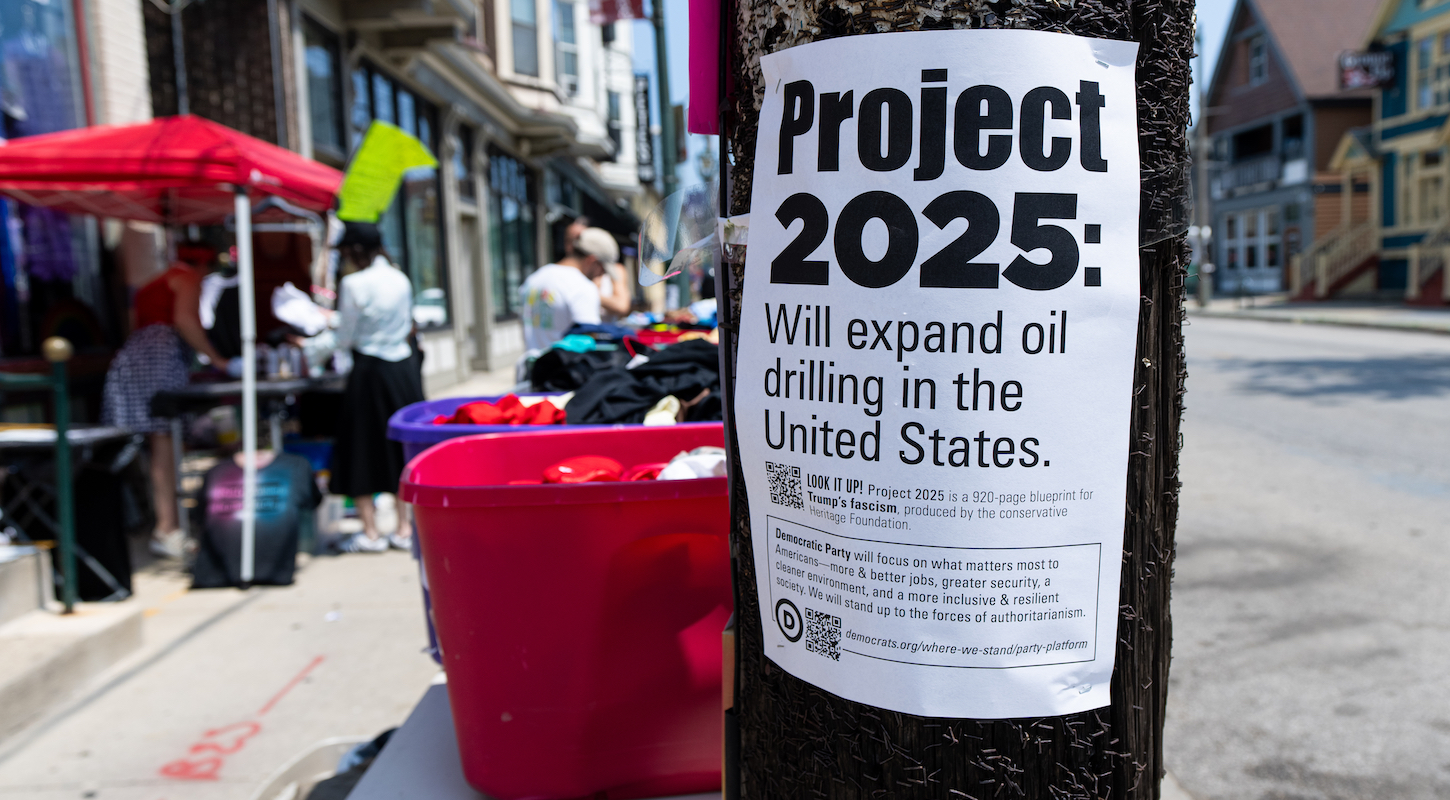

But another set of polls was considerably more dynamic. While the candidates were slogging along, the Democratic message-crafting group Navigator Research was asking how people felt about Project 2025, the 922-page strategic guide for a new presidency assembled through the Heritage Foundation by Trump's advisors and allies. In its June survey on the subject, Navigator reported that 71 percent of respondents said they didn't have an opinion about Project 2025; its most recent survey found that the no-opinion share had fallen to 46 percent—and that nearly all the newly developed opinions about it were negative.

American political campaigning and reporting has been built for generations on the premise that the voting public is hopelessly superficial. People here are expected to vote for the would-be president with the persona that impresses them, the person they think they would want to have a beer with, the one who seems most potently presidential. Sometimes they get mad about the price of gas and want to change things, but the assumption is that the nation holds a big popularity contest, where a genial actor or a charming rogue or an inspiring orator or a pugnacious showman wins a mandate against whatever cold fish or policy nerd the other side comes up with.

Yet here in 2024, in the maelstrom of personality politics, the public is attending to a whole big book of issues. Some of the forces driving that interest are non-wonky—Taraji P. Henson warned the audience about Project 2025 while hosting the BET Awards, making the subject take off on social media; Trump and his campaign clumsily tried to deny their involvement with it, giving the political press license to treat it as a scandal and a cover-up—but also it's a big, long document full of alarming and demented ideas, ideal for people to dig into and find their own points to warn other people about. It is an unsoftened product of the deepest right-wing ghoulosphere. To pick a topic more or less at random, it goes on for six pages about the importance of stopping the Department of Agriculture from feeding too many people, including urging a new Trump administration to "reject efforts to create universal free school meals" and abolish summertime school-meal programs for kids who aren't enrolled in summer school.

That people care about things like this is a genuine breakthrough. A longstanding problem for Democratic campaigns has been that voters don't like to believe Republicans could possibly support the policies Republicans support. In 2012, when Mitt Romney was running against Barack Obama, the New York Times reported in a profile of the Democrat-promoting Priorities USA Action PAC that "when Priorities informed a focus group that Romney supported the [Paul] Ryan budget plan—and thus championed 'ending Medicare as we know it'—while also advocating tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans, the respondents simply refused to believe any politician would do such a thing." In 2020, Data for Progress found that 45 percent of likely voters, and 81 percent of Republican ones, believed Republicans wanted to protect health coverage for preexisting conditions, rather than removing it; only 32 percent of likely voters, and 11 percent of Republican ones, understood that the party was in favor of dumping mining waste into streams.

This numbness was reinforced by the political media, which has long treated as unprofessional reporting on bad policy proposals if one party or the other hasn't already successfully turned them into lines of attack. Earlier this week, the Times' star newsletter writer David Leonhardt told his readers that Harris needs to sell herself to the public as a moderate (meaning, for Leonhardt, selling out trans rights), because "moderation works."

Leonhardt wrote:

Democrats often describe Donald Trump and other Republicans as radical. And today’s Republican Party is indeed radical in important ways. Many Republicans still claim that Trump won the 2020 election. Their party favors unpopular abortion restrictions and deep tax cuts for the rich.

But, he went on, "the average American considers the Democratic Party to be further from the political mainstream than the Republican Party." Gallup, he wrote, found that when it asked voters which candidate agreed with them most “on the issues that matter most to you,” Trump had led Biden 49 percent to 37 percent.

Nowhere in this account did Leonhardt raise the possibility that a person writing for a newsletter sent out to millions of people each day might have some responsibility to educate the public about where the parties actually stood on the issues, so that its members could hold better-informed opinions. In a similarly hapless vein, the Times' chief political analyst, Nate Cohn, wrote that Harris may have trouble trying "to advance a clear agenda for the future": "The party has held power for almost 12 of the last 16 years, and it has exhausted much of its agenda; there aren’t many popular, liberal policies left in the cupboard."

Cohn is an electoral polls expert, so apparently his model of political power and agenda-setting didn't include the Republican-dominated Supreme Court, which has put any number of popular policies back in play: the right to abortion, for instance, or keeping rapid-fire guns off the market, or the entire ability of the federal government to write and enforce regulations. But the public, especially on abortion, has caught on to the fact that these things are very much up for grabs. And now there's a lengthy guide to exactly what Republicans want to do if they grab them.

That people are paying attention to this may be Donald Trump's great contribution to national politics. Despite his total lack of interest in policy details, Trump successfully convinced the public that he's capable of doing anything. Once you've seen a mob smashing its way into the Capitol on Trump's behalf, it's easier to believe he would privatize the National Weather Service. Once you've heard Trump claiming that the mob was not his fault and no big deal, it's easier to ignore his disavowals of Project 2025, too. Trump has made America believe that old rules don't apply. That includes the rule that no major political party could have an agenda as unappealing as the one his party is working toward.