You couldn’t have missed it. In the trailers for the upcoming movie Creed III, the ninth installment in the Rocky Balboa Extended Universe, Michael B. Jordan’s Adonis Creed, son of Rocky’s foe-turned-friend, matches fists with Kang in the Quantum Realm … wait, sorry, wrong Jonathan Majors movie.

Anyway, Creed and Damian Anderson, played by Majors, are set to fight in Los Angeles’s Dodger Stadium. Now that would be a spectacle.

Given its location and iconic status, Dodger Stadium is a natural venue for movies and television shows. The climactic baseball game in The Naked Gun was played there (even if it involved the Angels and Mariners). Mr. Ed hit a home run off Sandy Koufax there. Fleetwood Mac filmed the video for “Tusk” there, and Elton John performed epic concerts there in 1975, recreated in the movie Rocketman.

But as a boxing venue, despite being more than 60 years old, Dodger Stadium’s history is limited. And that can be traced back to a fateful night in March 1963 when the ballpark, still gleaming new and symbolic of Los Angeles’s rise as an American metropolis, hosted the one and to date only boxing card in its history.

It was a tragedy.

When Dodger Stadium opened in 1962, it was heralded as the finest in baseball. The stadium contained luxuries now taken for granted. There was an exclusive Stadium Club and dugout-level box seats. Press box accommodations were the most sumptuous in the major leagues, and included showers and a dining area. There were no bleachers; instead what was called “pavilion seating”—general admission seats under the zigzag roof in the outfield. And of course, befitting the city of the car, there were acres of parking, enough for 16,000 vehicles.

The opening of the stadium was also hoped to bring a peaceful end to what had become known as the Battle of Chavez Ravine. The site of the ballpark was named for Julian Chavez, a 19th century Los Angeles supervisor who’d originally bought the land. By the 20th century, it had become a vibrant Mexican-American community.

Following World War II, much of the land was purchased through eminent domain by the city of Los Angeles, with the idea of building public housing. Families were cleared from their homes—sometimes by force. Ultimately, public housing plans were discarded, thanks to a concerted effort by local real estate interests, the right-leaning Los Angeles Times, and numerous others who called the idea of public housing socialism.

The anti-public housing forces marshaled together to get a man named Norris Poulson elected mayor in 1953. Poulson was an unspectacular legislator in Sacramento and Washington, but he swept in on a strong anti-Communist (and thus, anti–public housing) wave.

One of Poulson’s priorities was to bring Major League Baseball to Los Angeles. Its population was swelling, and it wanted all the cultural trappings of being a major city, and that included professional sports—the most popular of which in that era were boxing and baseball. The NFL had arrived in 1946 when the Rams decamped from Cleveland, but football was still nowhere near as popular. The major cities on the West Coast were home to baseball’s Pacific Coast League, which in 1952 was granted “open” classification, meaning the PCL was more than the minors, but less than a major league.

After a half-century of relative stability, the 1950s brought a wave of relocation. Before the 1953 season, the Braves, which had called Boston home for nearly 80 years, relocated to Milwaukee. The following season, the St. Louis Browns left for Baltimore. (Were it not for the Pearl Harbor attacks, the Browns might have relocated to Los Angeles a decade earlier. But that’s another story.) In 1955, the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City.

Even the Dodgers and Giants, New York mainstays, were looking at their surroundings and reconsidering. Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley was thwarted in getting the piece of property he wanted in Brooklyn—now the site of the Barclays Center. So he started looking elsewhere. In 1956, the Dodgers played seven “home” games at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, N.J., and in 1957, the Dodgers bought Wrigley Field in Los Angeles—home to the PCL’s Angels—and the associated territorial rights, as a prelude to a permanent move. Following the 1957 season, the Dodgers did just that, but didn’t use Wrigley Field at all. (In fact, the only major league team to play there was the Los Angeles Angels, in their expansion year of 1961. If the field is known for anything, it’s likely for its regular TV and movie appearances, and for being the site of the Home Run Derby TV show.)

In the Dodgers’ inaugural season in Los Angeles, they played at the Coliseum, a football and track stadium ill-suited for baseball. The Dodgers swapped Wrigley Field with the city of Los Angeles for the 315-acre Chavez Ravine site. That move was controversial, leading to court battles and ultimately, Poulson’s defeat in the 1961 mayoral election, which he attributed in part to the anti-baseball forces marshaled against him by his opponent, Sam Yorty.

Poulson might not have been popular, but the Dodgers sure were. By playing in the 100,000-seat Coliseum, they smashed every MLB attendance record, and won a World Series in their second season in Los Angeles. The Dodgers lost a three-game playoff against the Giants for the National League pennant in 1962, but drew more than 2.7 million fans in their first year at Dodger Stadium. (The Angels also used Dodger Stadium as a home field in 1962, referring to it as Chavez Ravine on broadcasts. They drew 1.1 million—good for sixth in the major leagues).

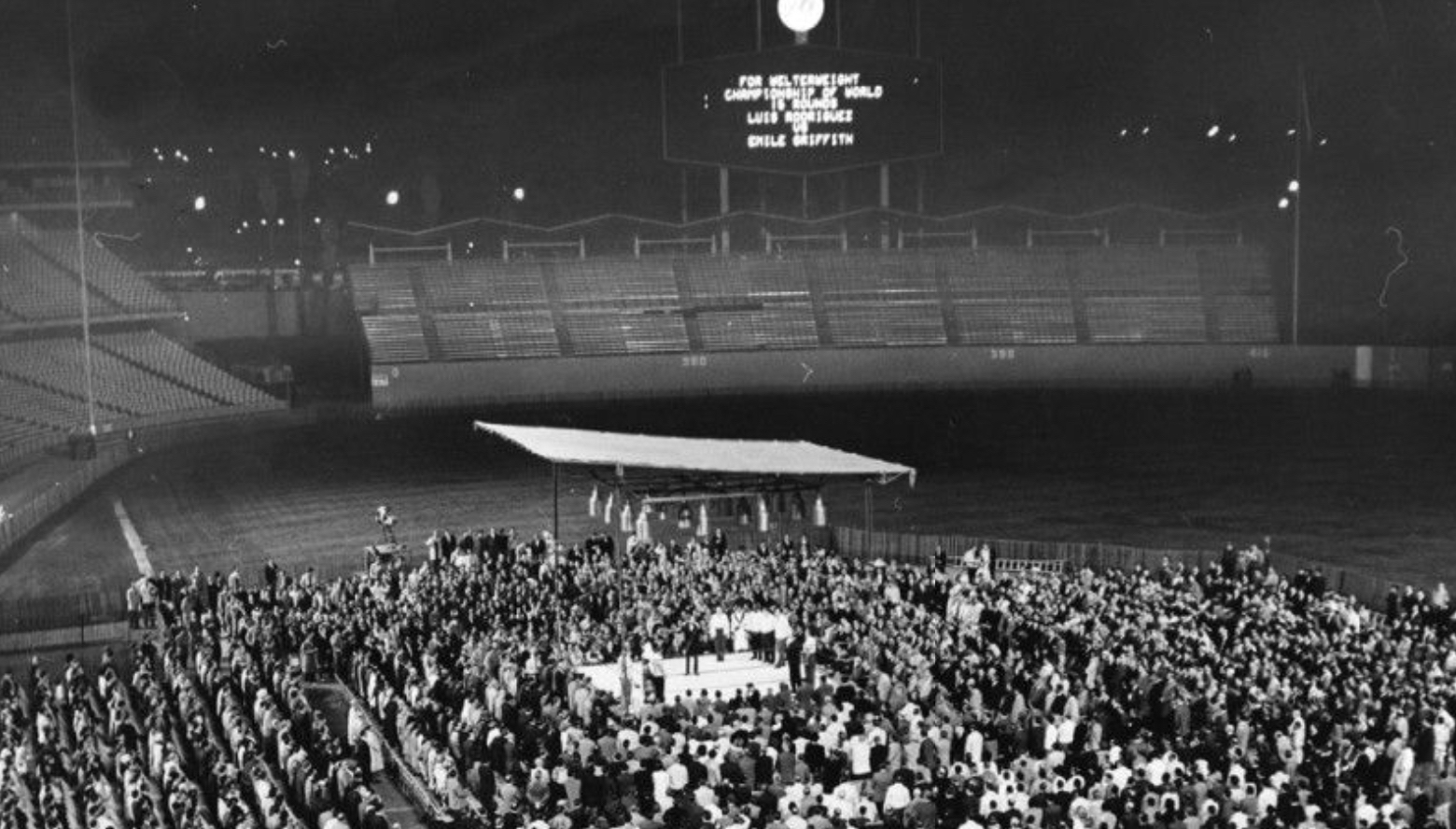

And there were more markets to tap into than baseball. O’Malley explored the use of Dodger Stadium as a venue for a fight. The ballpark was suggested as a possible venue for Cassius Clay and Archie Moore, a bout that ended up at the Los Angeles Public Auditorium. Instead, Dodger Stadium was scheduled to make its pugilistic debut with a card of three title matches—with the boxing ring atop the pitcher’s mound and the crowd on the infield—in March of 1962.

At the time, outdoor prizefights still held a whiff of magic to them. When Yankee Stadium was built in 1923, a decade before night baseball, it was built with lights installed for evening events like fights. Stadiums like the Polo Grounds, Municipal Stadium in Philadelphia, Soldier Field in Chicago, and Municipal Stadium in Cleveland were packed to the gills for the most prominent fights of the day. When Marlon Brando’s character laments that he coulda been a contender in On The Waterfront, he points to an opponent who he took a dive against, one who “got a title shot outdoors in a ballpark.”

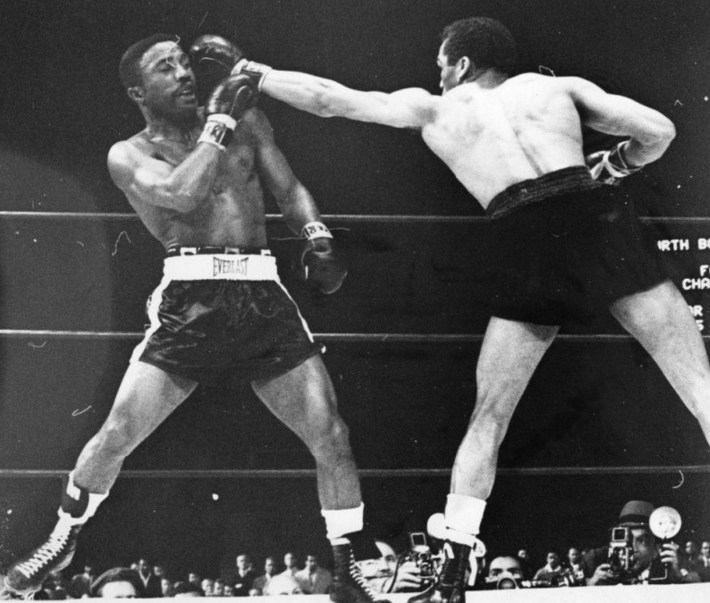

The signature match at Dodger Stadium would be a nationally televised title defense by welterweight Emile Griffith against Luis Rodriguez. Griffith had claimed his title almost exactly a year earlier, defeating Benny Paret in a notorious 12-round knockout at Madison Square Garden. The pair had fought twice prior to that, each winning one, and there was legitimate bad blood between them. During the weigh-in, Paret insulted Griffith, suggesting he was gay. In the 12th round of the scheduled 15-round fight, Griffith backed Paret into a corner and let loose with a barrage of punches, leading referee Ruby Goldstein to stop the fight. Paret never regained consciousness, dying 10 days later.

Also on the card was a junior welterweight bout between Raymundo “Battling” Torres and Roberto Cruz for the vacant title.

And in between those two matches, featherweight champion Davey Moore would fight Sugar Ramos, a native of Cuba who had moved to Mexico after Fidel Castro rose to power and banned professional boxing. Moore, at 29 the oldest fighter on the card, was an affable family man, married to his high school sweetheart and the father of five children. He’d boxed in the 1952 Olympics and had a ready-made nickname due to his Ohio hometown: The Springfield Rifle.

“The Moore-Ramos affair could well be a wild one,” the Associated Press predicted.

The afternoon the fight was scheduled, the heavens opened up, a rare occurrence in L.A. It rained sideways and the fight was postponed until the following Thursday, March 21; the schedule change meant it would no longer be nationally televised. Still, a crowd of 26,142 fanaticos—contemporary coverage made it a point to note how much of the crowd was Mexican, perhaps an attempt to exorcise some guilt over the Battle of Chavez Ravine—gathered to watch the fights.

Griffith and Rodriguez went the distance, and Griffith was certain he’d retained his crown. He’d even been hoisted atop his entourage’s shoulders in anticipation of the happy announcement. But judges called the fight unanimously for Rodriguez.

Then came the Moore-Ramos fight, “a slugger’s dream from start to finish,” Bob Myers of the Associated Press wrote. Contemporary accounts said that Ramos was winning handily from the sixth round on, and Moore’s corner stopped the fight in the 10th, because he’d taken such a pounding. “It just wasn’t my night,” Moore said in a postfight interview in the ring. He then answered questions from the press in the locker room, even joking with reporters. He was raring for a rematch.

“I was off,” he said. “That’s it, plain and simple. I just wasn’t up to my best.”

Reporters then left to watch the Torres-Cruz fight—a brief one, as it turned out, with Cruz knocking out Torres in the first round.

Moore, alone in the locker room with his trainer, Willie Ketchum, grabbed his head and said, “My head, Willie! My head! It hurts something awful!” He fell into unconsciousness and was taken to White Memorial Hospital. A little more than three days later, Davey Moore was dead.

The reaction to Davey Moore’s death was swift and predictable: People from all walks of life were horrified. Jimmy Cannon, the New York sports columnist at once attracted to and repelled by boxing—he called it sports’ red-light district—proclaimed, “No one is to blame for the death of Davey Moore. Yet so many are guilty.”

Similar sentiments were found in songs written soon after. “Who Killed Davey Moore?” Bob Dylan asked, pointing the finger at the opponent, the referee, fight fans, and the sporting press, all of whom demanded violence.

“The fighter must destroy as the poet must sing,” Phil Ochs sang in “Davey Moore,” “as the hungry crowd must gather for the blood upon the ring.”

“This was an accident, but it was also premeditated,” Cannon wrote. Really, it was an accident. In the 10th round, Moore had fallen backward, the base of his head striking one of the ropes, in actuality a steel cable, bruising the base of his brain stem. A hemorrhage or brain swelling could be operated on. This could not. Doctors said it was a one-in-a-million type accident.

That didn’t mute the reaction that came from seeing Moore’s wife Geraldine, who had come to Los Angeles with her husband but didn’t attend the fight, admitted to the hospital herself for exhaustion after her husband died.

Senator Estes Kefauver, who’d distinguished himself a decade earlier by chairing a committee to investigate organized crime, called for national regulation of boxing, then governed by a patchwork of sanctioning bodies and state athletic commissions.

U.S. Rep. Hugh Carey, whose Congressional District included part of Brooklyn, and would later be elected governor of New York, called for an outright ban on boxing, as did California Gov. Pat Brown, citing not just Moore’s death but heavyweight boxer Alejandro Lavorante, who’d been seriously injured in a fight the previous September and remained comatose in a hospital bed in California. Lavorante would eventually be taken back to his native Argentina, where he died in April 1964.

Even the Catholic Church weighed in. “It is barbaric to pit brother against brother,” Pope John XXIII said. (The Vatican later put out a statement that the Holy Father had been misquoted.)

Following a service in Los Angeles—where an estimated 10,000 people filed past his body—Davey Moore was returned to Ohio. Another estimated crowd in the thousands viewed his body at the local junior high school in Springfield, and mourners packed the small church for his service, with hundreds more outside. Gov. James Rhodes, who attended Moore’s viewing, hired Geraldine Moore, giving her a state job to support her family.

Extra padding was added to boxing ropes, but Moore became a largely forgotten figure in boxing. (Dylan’s song about Moore isn’t even his best-known song about a prizefighter.) Sugar Ramos lost his title the year after beating Moore, but fought as a professional boxer until 1972.

In 2013, 50 years after his fatal fight, a statue of Moore was put up in Springfield. Ramos attended the dedication. The only time he’d met Geraldine Moore was when she saw him in Davey’s hospital room, weeping. (“I want to be champion of the world, but not at this price,” Ramos had said.) Geraldine Moore had believed Davey’s death was nothing but an act of God, and 50 years had done nothing to change her opinion. Together they viewed the statue, and visited Moore’s grave.

“I saw what I needed to see,” said Ramos, who died in 2017. “I was at ease, and I wasn't afraid. It was totally different. There was peace and tranquility.”

In the wake of the fight, Walter O’Malley decreed that boxing would never be held again at Dodger Stadium. The O’Malley family sold the team in 1998, and to this day, his decree has been honored—though maybe not for lack of trying. Dodger Stadium bid to host the Canelo Alvarez–Gennady Golovkin fight in 2017, but lost out to Las Vegas. As teams try to squeeze every buck out of their venues’ off-nights, it is probably only a matter of time before Dodger Stadium hosts a major card outside of the fiction of Creed III. When it does, there may be some ghosts in attendance.