Now that the wholly unsatisfying World Series is over and we can move on to the bliss of things that don't take four hours for no good reason (and yes, we are looking at you, Illinois and Penn State, you dilatory hyenas), we can move on to things that might take four weeks or four months for no good reason. You know, the show you've all been waiting for.

The MLB lockout.

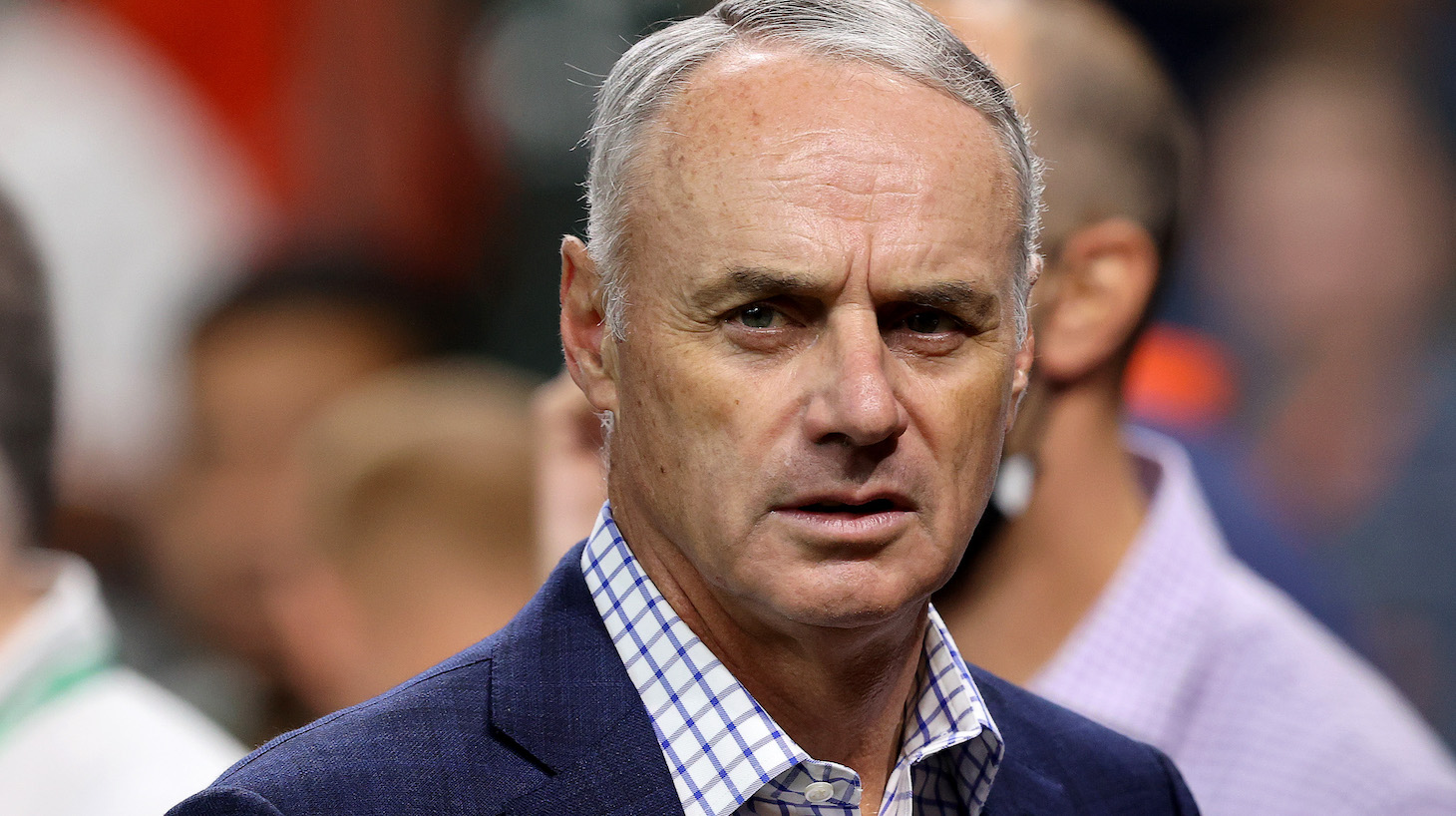

Come 11:59 p.m. December 1, the current collective bargaining agreement between the oppressors and the oppressed will expire, and because we like to be open-minded about these things, we will let you decide on your own which side is which. Nobody is expecting a happy ending, largely because the two sides have moved back to the familiar turf of mutual hatred and distrust, as God intended. Tony Clark and Rob Manfred will bicker about a thousand things, get rid of most of them and end up arguing about money because, yeah, that's the problem with modern baseball. Money. Everything else is sweet and dandy.

The fact that the game continues to repel more people than it attracts won’t be addressed at all, because there are way more lawyers and accountants than lyricists and aesthetes. Why try to convince everyone on both sides of the mahogany to agree that the thing they're all trying to sell isn't selling nearly as well when you can have much more productive middle fingers expended on subjects like how many employees can be replaced with robots? You can safely bet that the notion of baseball as a disappearing art form will not be raised by either side at all, probably because nobody remembers the disappearing Cheshire Cat from Alice In Wonderland for anything beyond his all-is-well smile.

No, this seppuku-fest will boil down to the same thing the others have: the revenue split, because what else could possibly matter? Both labor and management are fighting for the quarters that fell off the table and are toward the floor-installed heater vent, and the notion of preserving/improving the game isn't one of those quarters. The players' share has been shrinking, as shown by a declining average salary and service-time manipulation and an increase in tanking. The owners are in favor of all these things and will negotiate with their usual wild boar deftness, so we can expect talks to be brief and not only unproductive, but profane and threat-laced. I mean, if we're all living right, that is.

This should come as no surprise to you who have been paying attention. All lockouts are baseball-free but leverage-rich enterprises, what baseball fan doesn't love arguing about leverage? Baseball hasn't had a work stoppage in 27 years, but that was under the often befuddling but generally conciliatory Bud Selig as commissioner. Rob Manfred is there now, with all his many charm (singular), and his 30 clients are by all accounts spoiling not for a fight but for a rout. They want all that money lost in the pandemic, and since their TV contracts have already been extended to 2028, the most obvious place to haul in new money is by withholding it from the players.

Plus, you can tell that they're in a bit of a mood, and the expected negotiating rigidity they will exhibit will advance the 2020 and 2021 experiments MLB tried out to improve the game by making less of it available. Sure, COVID was the impetus for 2020, but 2021 too gave us the gutting of the minor leagues, the seven-inning doubleheader, and the ghost runner—all intended, we suppose, to remind us that baseball as a national pastime works better in management's mind as less pastime, and less national. Hell, Manfred said exactly that when defending Atlanta's double-down on its fetish for racist iconography. Maybe it's time we all took his word for it, even if it is just in his role as proxy marionette for the owners. December 1 will come and go, crocodile tears will flow like rivers on December 2 as everyone pretends that what they all knew was coming has finally come, and we will take one step closer to the economic and emotional model that the people who run baseball think is the best for all:

The Cheshire Cat.