In the spring of 2021, ballet dancer Ramona Kelley returned to her Washington Heights apartment to find a surprise in the middle of her bed: a single stick and a little white ball. At first sight, Kelley assumed some neighborhood kids had accidentally thrown a ping-pong ball into her bedroom. But when she picked it up, it looked and felt just like an egg. Kelley's eyes travelled to her window, which she had left ajar. "I can't believe that this is real," she remembers thinking. "She laid an egg dead in the middle of a nice, comfy memory foam mattress and protected it with one stick."

Kelley suspected the egg had come from a pigeon, in part because she had pigeons on the mind. Just weeks earlier, Kelley watched her cousin, the evolutionary biologist Elizabeth Carlen, present her dissertation on urban pigeons. Kelley texted Carlen: "It's a pigeon emergency." When Carlen saw a photo of the single, pathetic twig, she knew it was indeed the work of a pigeon—a bird infamous for its shoddy-looking nests.

Carlen advised Kelley to throw the egg away. "You don't want that bird coming back and thinking that it needs to raise this offspring in your bed," Carlen told her cousin. "And don't leave that window open for a while because she will come back."

Birds build all types of nests, many of which are intricately and painstakingly crafted. An American robin builds a soft, sturdy cup out of dead twigs and grass, and reinforces it with mud. A Baltimore oriole weaves a pendulous pouch of fibers that is strong enough to carry seven eggs and last for four months. A kiwi uses its strong toes and claws to dig an immaculately camouflaged burrow. And a city pigeon arranges sticks in an often haphazard pile.

I love pigeons because when it’s time to make a nest they’re like “fuckin whatever” pic.twitter.com/pKZfvn2RPP

— worms cited (@christapeterso) June 10, 2022

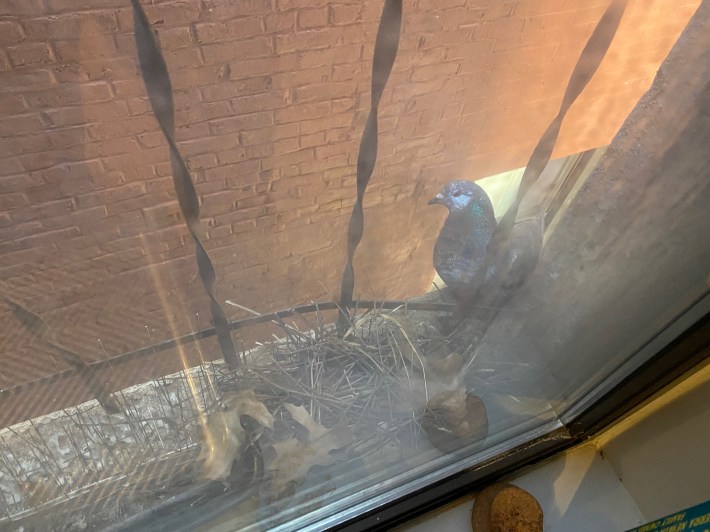

"It's the loosest concept of a nest," said Rosemary Mosco, a science writer and the author of A Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching. Without the presence of eggs, the average pigeon nest could pass as a coincidental aggregation of twigs or jumble of debris. To our human eyes, a pigeon nest looks objectively half-assed. It is a nest that seems to mock other nests.

There is an entire Twitter account, @BadNests, devoted to chronicling "the worst nests that pigeons have to offer." The images include a nest made on a doormat, a nest cradled in the windshield of a car, a nest that has no sticks at all but is simply an egg laid in a colander. Looking at a pigeon nest, you might even feel embarrassed for the pigeon—you live like this?

But just because pigeon nests look useless to us does not mean they are useless to pigeons. Most humans, as non-birds, have no relevant expertise in evaluating whether a nest is good or bad. "There's this idea that the whole group of pigeons and doves are notoriously not the best nest-makers, but that's putting our own human constructs on it," said Carlen, now at Washington University in St. Louis, who is one of the few humans actually qualified to judge a pigeon nest.

To appraise whether a pigeon nest is good or bad, you must try to understand the nest from the perspective of a pigeon. As Carlen sees it, a pigeon nest has one ultimate goal: to create an area where the egg will not roll away.

Feral city pigeons descend from wild rock doves, a species known as Columba livia, which nest on rocky cliffs. While the irregular, swaying branches of a tree might require an intricately woven cup nest, cliffs offer larger, flatter surfaces where a pile of sticks might be more than enough to keep an egg in place on an outcropping. "What pigeons are trying to do in the city is to do what they did when they were wild," Mosco said. "Their only requirement for nesting is a flat surface, and we don't tend to build not-flat ground."

Our cities teem with graciously level scaffolding, fire escapes, windowsills, and air-conditioning units, which make it even harder for an egg to roll away. So city pigeons need to do even less to build an adequate nest. "Why would I waste more time putting together a more well-crafted nest if it's going to serve the same purpose?" Carlen asked. "When I could spend that time out feeding or courting ?"

— Bad Pigeon Nests (@BadNests) June 12, 2022

Carlen and Mosco also pointed out that for many domesticated pigeons, housing was part of the bargain. As early as the Iron Age, people constructed honeycombed palaces called dovecotes to house the birds. "It looks like a large upside-down colander," Carlen said. "There are lots of places for the birds to come in, sit and hang out and feel protected."

Unlike some other bird species, both male and female pigeons sit on their eggs, meaning the nest is under constant supervision. "There's never a moment where the egg is not being sat on," said Colin Jerolmack, a sociologist who studies human and animal relationships at New York University. So it's probably not going to just roll away.

Pigeons don't just sit on their eggs; they also sit on their young until they are nearly full-grown. "Sometimes you'll see them sitting on a large pigeon that's almost as big as they are," Jerolmack said. As the fledglings grow, they will feed on crop milk regurgitated by their parents, a non-dairy beverage that is roughly the consistency of cottage cheese. Perhaps a fully-occupied pigeon nest cradling large babies and a puking parent, no matter how few twigs in it, would not seem so stupid-looking.

And some putative pigeon nests that have gone viral for their badness may have been staged, Mosco suggested. She pointed to a photo of three white eggs laid on a sink full of used syringes, which was originally tweeted by Michelle Davey, then the Vancouver police superintendent, along with the hashtags #opioidcrisis #fentanyl #frontline #notstaged. Besides the fact that pigeon parents almost never stray from sitting on their eggs, Mosco added that pigeons usually lay only two eggs per breeding cycle. "I don't know that a pigeon could carry syringes," Mosco said. "Pigeons have always been used as a way for us to comment on perceived social ills."

To truly test the success of city pigeon nests, researchers would need to monitor nests over time to determine how many birds hatched, fledged, and made it to adulthood. But the pool of scientists who study city pigeons remains relatively small. "There are so few of us," Carlen said. "Because I think people don't realize how interesting they are."

People tend to think of pigeons as stupid animals, Jerolmack said. "We have this idea that they're dumb, and then we go looking for evidence of that. You say, well, 'look at the nest that robins built versus the nest the stupid pigeons built.'"

— Bad Pigeon Nests (@BadNests) June 11, 2022

But, just as it is ridiculous to judge a pigeon by the standard of a robin, it is ridiculous to judge a pigeon by the standard of a human. Our own conception of intelligence is an extremely limited and somewhat ridiculous way to judge other animals, who sense and understand the world in ways that would boggle our human brains. But these birds have proven themselves rather smart even by our own definitions. In the 1990s, scientists trained pigeons to distinguish between impressionist and cubist paintings, pecking on switches to identify Monets from Picassos. More recently, scientists trained pigeons to identify cancer in biopsy images of breast tissue with 99 percent accuracy.

A pigeon's capabilities extend beyond visual tasks. When people try to drive pigeons out of cities, the pigeons often come out on top. "You put netting up, you gas them, you shoot them, you put spikes up, all of these methods basically fail," Jerolmack said, adding that these efforts might be successful in temporarily displacing pigeons. The only sure way to reduce populations is to systemically reduce food sources, an extraordinary task considering pigeons are general eaters that can survive on our food waste.

Some of our efforts to bring the pigeons down may only lift them higher. When New York City resident Kevin Webb installed spikes outside his windowsill after pigeons nested there and reared a chick, the pigeons returned and nested on top of the spikes. "Those are really great places to look for a nest," Carlen said. "You're basically providing an area for them to build out and add a couple of sticks that they can lay their egg in."

Pigeons can lay a clutch of two eggs every two to six weeks. Although it might seem that breeding this frequently contributes to crappy, low-effort nests, Mosco explained that frequency has nothing to do with quality. Not all pigeons breed year-round; in colder areas, the birds will not breed in the winter. Pigeons also often reuse their nests, adding material (and poop) to their twig pile over time. Mosco noted that some bird species which nest seasonally also have terrible nests. "Fairy terns lay an egg on a branch and that's it."

Ultimately, pigeons do not make fancy nests because they do not need to make fancy nests, Mosco said.

If you happen to encounter an unwanted pigeon nest somewhere in or near your personal space, Carlen recommends moving it, as pigeons have excellent homing abilities. And if you want to encounter a pigeon nest at a respectful distance, listen for the calls of baby pigeons. "It's an incredibly high-pitched squeak that is hard to miss," Jerolmack said. Look toward covered places that could protect the birds from rain and predators. In New York City, a surefire way to spot pigeon nests is to look under bodega awnings.

Every pigeon living in the United States is a feral domestic C. livia, a species native to Europe and North Africa, which colonists brought over to the Americas. European colonists drove North America's own native passenger pigeon— which was such a valuable food source that the Seneca people call the birds jah’gowa, or "big bread"—into extinction in the mid-1800s, according to A Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching. Pigeons are even more numerous in urban settings than in their native environments, according to Jerolmack. "They've entirely altered their their evolutionary trajectory, their behaviors, their routine to surviving and thriving around people," he said.

So we cannot in good faith insult these pigeons without taking accountability for how we shaped their current existence. We domesticated them for our own purposes, raising them for meat and messaging, and when they escaped or when they no longer served us, we abandoned them and called them rats with wings. They are, whether we like it or not, some of our longest-running companions. "They spent thousands of years living near us and becoming even more tightly intertwined with us," Mosco said. "So when I see a crappy pigeon nest next to someone's door, I have a lot of sympathy for them."

However. Even the researchers who have devoted their fields of study to pigeons, who seek to redeem the birds from the realm of pests, even they will admit that some pigeons do make questionable nest decisions. Jerolmack's friend texted him a photo of a nest consisting of a single piece of straw on top of an air conditioner. The nest on Kelley's bed may also seem like a bad choice. After all, it was dismantled before the egg could hatch. "I've never built a nest, so I can't really judge," Kelley said. "She found a memory foam bed. It was a great plan. Unfortunately, I also lived there."

In another light, the bed nest cleared the most important standard of a pigeon nest: that egg was not rolling anywhere. A pigeon has no sense of private property. And for its brief existence, the pigeon's egg may have rested on the most comfortable, luxurious nest in all New York City. Consider the twig a garnish.