In February, in Florida, a pink snake about as long as a banana shot for the moon but definitively did not land among the stars. Upon encountering a leggy feast—a scrumptious Caribbean giant centipede—the little snake opened its jaws and began swallowing the centipede until something went haywire, killing everyone involved and leaving the snake still mouthing the centipede's derriere, like an earthworm attempting to eat a comically long sub.

The duo died in John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, where they were discovered, still entangled, by a park visitor. A biologist with Fish and Wildlife recognized the small pink snake, snapped a picture and emailed it to a slew of snake experts. When Coleman M. Sheehy III, a researcher and the herpetology collection manager at the Florida Museum, opened the email, he couldn't believe his eyes. The photo depicted the rim rock crowned snake Tantilla oolitica, a rare species that is even more rarely seen. The snakes burrow underground in limestone, meaning scientists know almost nothing about what the snakes eat or how they spend their days. "You can look and look and look and look and look and look, you can spend years doing it and never find one," Sheehy said. But now here was a rim rock crowned snake whose peculiar passing revealed new insight into how it lived its life—chowing down on big snacks.

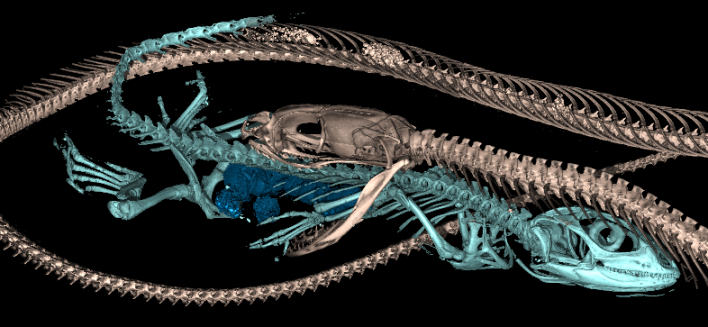

"I was just, like, flabbergasted," Sheehy said. He emailed back and asked for the specimen to be sent to him immediately. When the entwined corpses were hand-delivered to his home on a Saturday morning, Coleman whisked them away to the Florida Museum. It seemed obvious that the snake had died while eating the centipede. But did it choke, or was it bitten by its prey from the inside? This question could only be answered by a CT scan, which could peer inside the snake's body like a digital autopsy to understand where and how things went so wrong. The results of this autopsy were published Sunday in the journal Ecology.

The day earlier, Sheehy had asked Jaimi Gray, an evolutionary morphologist and CT-imaging specialist at the museum for advice on how to pose the snake in preservative to enhance the soft tissue contrast. Formaldehyde locks tissues in whatever position it's placed in, meaning a coiled snake will be coiled for eternity. And though coils may appear sophisticated, they're a pain to scan. "You need to get enough power in your X-rays to penetrate multiple layers of snake," Gray said. For these particular scans, the ideal shape was a hairpin, where the snake is folded in half. "Then you only need to get through two layers of snakes," she said.

The researchers had no idea how long the snake had been decomposing in the sun, during which time its internal organs could have turned to "total mush," Sheehy said. "The scan would have been a gray glob." But this, thankfully, was not the case. "The images are just outstanding," said Vicente Mata-Silva, a herpetologist at The University of Texas at El Paso who was not involved with the research.

Sheehy and Gray hope this technique could be used to scan other specimens of rare, elusive snakes and see what might be stored inside their bellies. They hope to find more rim rock crowned snakes—ideally alive, but they're not picky.

Once Gray had the scans, she peered into the trachea until she reached a point where all the air was totally cut off, coinciding with the tubbiest part of the centipede. "It takes up the entire snake," Gray said. "There's no room for anything else in there." Gray also found an injury—a chip in a snake's scale—that seemed tiny on the outside but more extensive on the inside. The wound could have come from the centipede, or something else. And other Tantilla snakes are presumed to be resistant to centipede toxins, suggesting that rim rock crowned snake may also have some protection. "But the fact that the trachea was crushed makes us think that this was asphyxiation," Gray said.

In Mata-Silva's eyes, the authors made a good case pinpointing asphyxiation as the immediate cause of death. But in this particular case, he added, "we cannot tell if the snake died from asphyxiation alone or from a combination of asphyxiation and the centipede bites." (If you personally want to peer inside the snake for your own unofficial autopsy, Gray's CT scans are available online here.)

The tragic saga of the hungry, hungry rim rock crowned snake and the fatally voluptuous centipede raised some questions for me. Snakes are famous for several things, but the top two are probably "not having legs" and "eating things that seem too big to be eaten." Snakes can do this because the joints between many bones of their skulls and jaws are very flexible. They can open their jaws very, very wide and wrap their mouths over prey, snag the meal in their teeth, and then move their upper and lower jaws independently of one another to slowly encompass the lump. "With a large prey item, it's not so much that they're pulling the prey in, but working themselves over the prey as they eat," Sheehy said. Needless to say, this can take a while.

This is how pythons can eat wallabies, pigs, antelopes, and even small leopards, and how egg-eating snakes can eat eggs. One Burmese python in Florida was found with the digested remains of three deer—one doe and two fawns—in its belly. Some snakes, like the Eastern kingsnake, are even known for eating larger, longer snakes—an act that seems to defy at least one law of physics. I couldn't help but wonder: How does a snake know when food is too big to eat? And conversely, how often does a snake miscalculate to the extent that they wind up dead, mid-bite? Are the snakes in Florida just eating on another level?

Apparently, scientists told me, this happens more often than you might think. Wildlife researchers found a very ambitious but dead 13-foot Burmese python with an intact six-foot-long American alligator spilling out of a hole in the python's belly (also in Florida, duh.) Snakes have died swallowing too-big geckos and other snakes, and one snake even died eating a worm lizard, which is a limbless reptile that is not a snake. One snake even died after swallowing a larger, heavier centipede that managed to eat its way out of the snake's body (both eaters died in the process). Just last summer, Mata-Silva and his students found a dead juvenile rock rattlesnake that had successfully swallowed an entire adult marbled whiptail lizard but also stopped breathing sometime during the process. "It was impossible to reach a definitive answer due to the snake’s advanced state of decomposition," Mata-Silva said. And Gray shared some gnarly CT scans of snakes "choking on things" including a lizard and frog.

As long as a snake isn't choking on its too-large meal, there is generally an easy fix for buyer's remorse. "Sometimes when snakes eat large prey and they really just realize that their bodies can't swallow it, or something's wrong, they regurgitate it," Sheehy said. Snakes can also regurgitate meals as a defense mechanism—it's hard to escape danger when you've got an antelope gradually dissolving in your belly acid. But the rim rock crowned snake apparently could not upchuck the centipede for a number of reasons, Sheehy noted. Some plausible hypotheses: the arthropod may have been too stuffed into its esophagus to be vomited quickly enough for the snake to breathe; its legs may have snagged inside the snake; or the snake may have been weakened by a venomous bite. Or maybe it was a combination of the three. Alas!

Why do some snakes bite so close to the sun? Several of the few studies documenting this phenomenon report it happening in young snakes, who may overestimate their ability to subdue and swallow big snacks. While Sheehy notes that there is not enough data to necessarily conclude that young snakes tend to do this more, it's quite possible that realizing when a meal is too large to fit inside your body without killing you might be wisdom and humility that only come with age.