Willie Mays, who died Tuesday at the richly merited old age of 93, was baseball itself, more than anyone else ever connected with the game. Not just the best player, which he was. Not just the most joyful great player, which he also was. Not only the most extravagantly gifted of all the five-tool players that played during the richest era in the game's history, although he absolutely was that as well. He was baseball, period, full stop.

His presence reaches back to the dying embers of the Negro Leagues, and the New Yorkiest decade in the sport's history. Mays was an everyday player all summer and then barnstormed through the offseason in the '50s; the margins were so narrow, then, that he could not have stopped if he wanted to. He became a star with the Giants and then the most recognizable face of the game's westward migration to Los Angeles and San Francisco; his career unfolded dazzlingly from one side of the country to the other and back, and then he retired to become the direct link to his godson Barry Bonds, whom he mentored in all things about the sport. This is roughly the scope and shape of his career, but it was not Willie Mays.

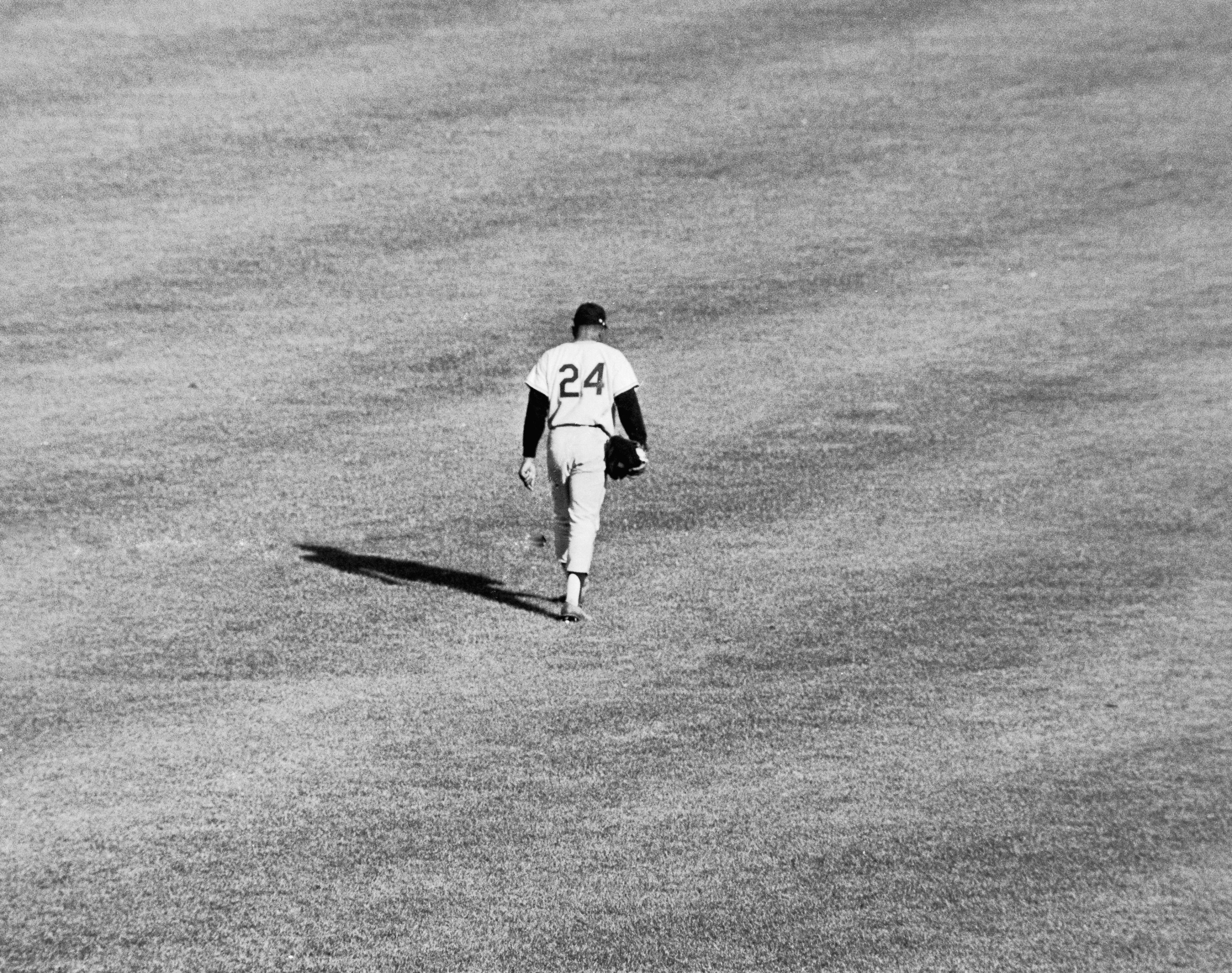

Mays was the basket catch and the hat flying off his head on every barely controlled first-to-third. He was not the best player ever at anything, but remains among the very best ever at everything imaginable. He was the de facto on-field manager of the Giants in the mid-'60s, calling pitches and positioning infielders from his post in center field because everyone on the club deferred to his superior knowledge and instincts. He was traded back to New York at age 41 by the cash-strapped and deeply foolish Giants owner Horace Stoneham, who valued manager Charlie Fox, whose career managerial record was 377-371, more than Mays. It’s one more item that feels ripped from today's smartphone screens.

Mays was even part of baseball’s strange, sad dance with sports gambling without ever making a bet, suspended six years after his playing days ended for doing promotional work—that is, greeting folks—with Bally's and refusing to walk away from his contract when cardboard-plated lumpencommissioner Bowie Kuhn threatened him with a suspension. It is instructive that neither the casino nor New Jersey had legalized sports betting at the time, and that Mays was forbidden from betting at all by the casino. It is equally elucidating that among the first things Peter Ueberroth, Kuhn's successor, did was to reinstate Mays and Mickey Mantle, suspended four years after Mays for the same flimsy offense. Baseball no longer runs from gambling; it is all but run by it. Here as everywhere else, there is the sense that Mays was ahead of his time, or just turned up too early.

It is worth taking a moment to consider just how much baseball history Mays covered. His first at-bat with the Negro League’s Birmingham Black Barons was in 1948, when he was 17; his last was with the Mets in 1973, when he was 42. He was everything baseball has been for the greatest percentage of its history, and even the one near-gap in his resume, his sole World Series ring in 1954, is forgivable because the great Giants teams of his era were just a hair less great than the Dodgers of the same span. If there is a god who does baseball, Mays should have had many more just on general principle. The last memory of him as a player, pinch hitting and losing fly balls in the sun during the 1973 World Series, is almost an act of cruelty. It showed him as the one thing he never seemed to be: old.

But if that was Mays at the end, it was also not the Mays that was baseball, and who stayed lit up in the memory well into his casino-greeter years and beyond. He was the best player in an era when nearly every team had a Hall of Famer in the regular lineup. Mays was there at the moment when talent replaced race as the sport’s prime directive, when even the most recalcitrant segregationist owners finally found the time and financial inclination to teach their scouts color blindness; when the sport finally became what it could be, Willie Mays was something very like the living fulfillment of that promise. He has the third-greatest career WAR among position players, behind only Babe Ruth and Bonds, and that list would look different if he hadn't lost most of his second and all of his third seasons to the draft. His aura extended well beyond his playing years or even his reinstatement from Kuhn's Fortress of Pettiness. He won the Presidential Medal of Freedom, was a hitting instructor for the Mets, worked in the Giants front office as their ambassador of choice, had the World Series MVP named after him, and was even the subject of this song, which absolutely slapped for its time. It is less quantitative than that WAR figure, but Mays was by any measurement and in all ways the single coolest player the game has ever seen.

He spent his last years with compromised vision and may have even been blind for several years, though that was never confirmed. But he saw enough for long enough to see himself revered in all corners of a sport that has needed a logical inheritor to his place in its history for half a century. It was almost Henry Aaron and Frank Robinson and Roberto Clemente and Ernie Banks and Willie Stargell and Billy Williams and Sandy Koufax and Bob Gibson and even his younger compatriot Willie McCovey. It could have been Bonds. It may someday be Shohei Ohtani. But there won't ever actually be another Willie Mays. Different days, different ways, an entirely different world, but also an imprint that survives long after the man who left it.