New York has always arrogated to itself the power to bestow Bigger Than Life status on its sporting heroes, going back to Babe Ruth. That is no longer a unique skill, but New York made the myths better earlier because it had the most teams, the most media, the most people and the loudest voices with which to shout down all the other contenders. Over time, that power became more diffuse and democratized, but most sports fandom has been defined in considerable part by New Yorkers setting the parameters of the conversation and having the most platforms available to dominate it.

But of all the heroes New York claimed as their own, whether they came from Baltimore (Ruth) or San Francisco (Joe DiMaggio) or Victoria, B.C. (Lester Patrick) or Los Angeles (Frank Gifford) or Beaver Falls, Pa. (Joe Namath) or Fresno (Tom Seaver) or Wyncote, Pa. (Reggie Jackson) or Montreal (Martin Brodeur), none had a more theatrical moment of their own than Willis Reed. None did less image-making off that moment, either.

Reed, who died Tuesday at age 80, is probably the most iconic Knickerbocker even now—even more than Clyde Frazier, who was Reed’s teammate on the last Knicks team to win a championship and has been part of the team's TV broadcasts for decades. His entire career was, is, and will surely be reduced to the one night in May of 1970 when, burdened by a torn thigh muscle, he still gimped onto the floor before Game 7 of the NBA Finals against the Los Angeles Lakers to a guttural and communal roar from the Madison Square Garden crowd, made his first two jump shots and was credited from that moment to this one as the reason the Knicks won their first of two NBA championships. He defeated the Lakers on one leg, or so goes the legend.

Whether he did or didn't stopped mattering long ago, because it turns out, the myth always beats the reality. Reed played 27 minutes but was otherwise mostly a decoy in that game; dragging a dead leg behind him, he deferred to his teammates, most notably Frazier, whose 36 points and 19 assists were the truth upon which the Reed narrative has always rested. But the cameras caught Reed unilateraling out of the Madison Square Garden tunnel and onto the floor, and the crowd's response was what it was, and that was all anyone needed to know. The rest, including the 113-99 final score, was merely extraneous detail. We have the image, and the image is sufficient. It’s not the true story, but it is the story that satisfies.

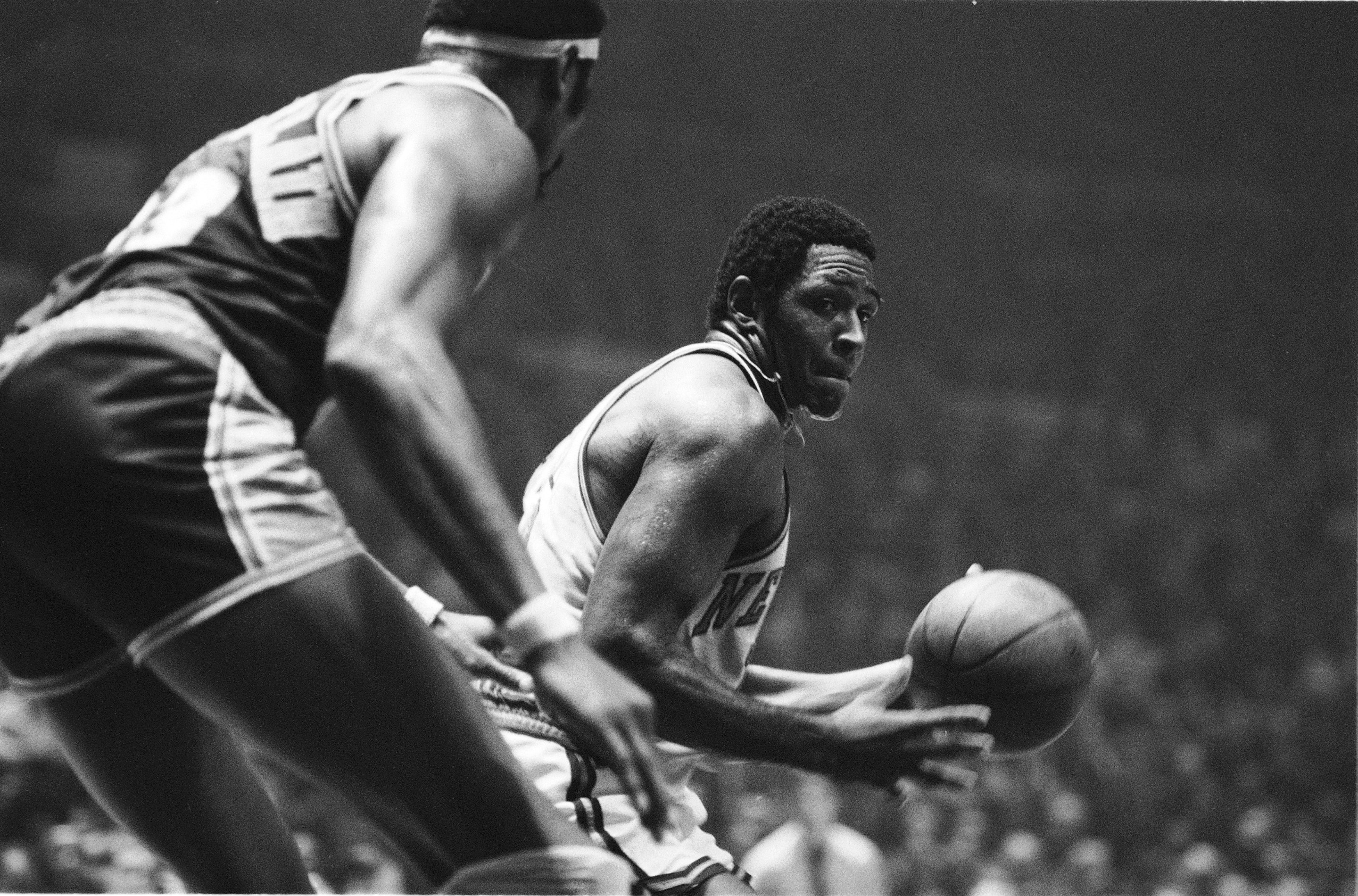

Reed was not a self-aggrandizer, and that constitutional unwillingness to chase publicity allowed him to complete his career on his terms. He was a player who specialized in heavy lifting against bigger, wider, less mobile centers, and his raw numbers, while impressive, were sub-gaudy. Still, he was sufficiently essential to the firmament of New York that he was named Finals MVP in both of the Knicks' championships, and coached the Knicks and later the then-New Jersey Nets.

He was what soccer aficionados like to term a "hard man," someone who made his name by making your night a misery. He scared opponents by being that guy you never messed with, and there are many stories of him being willing to fight disrespectful opponents and them RSVPing no. There is one apocryphal story, also attached to St. Louis mega-badass Zelmo Beaty, that Reed offered to fight an entire benchful of players one night and his offer was unanimously declined. He was part of the class of non-Russell/non-Chamberlain/non-Abdul-Jabbar Hall of Famers—think Nate Thurmond—who were glorified by the basketball knowers of that age, but he also had the one genuinely iconic moment that lasts forever. Even Basketball Reference, the most dispassionate of websites, lists the 1970 Game 7 as "The Willis Reed Game."

That game is ultimately one of the very few moments in any city's sports life to be elevated beyond a team's first-ever championship. It is bigger than Ruth's Called Shot because people still argue about whether that one actually happened, bigger than Namath running off the field in Super Bowl 3 with one index finger raised to the sky, or Messier's skate dance after the Rangers won their last Stanley Cup 29 years ago, or David Tyree's helmet catch in Super Bowl 42. It’s as big as it is, even still, because Reed always seemed content to let it be what it was; the legend spread as legends used to, by word of mouth and images of his two jumpshots. Reed himself never really said much about it, and he didn't have to. He did the perfect thing at the perfect time when everyone was looking, and then let it speak for itself. The lasting moments are like that.