Welcome to Hey It's That Guy, a series celebrating a selection of character actors and spotlighting, in detail, the under-appreciated, singular traits that make them so indelible.

There’s obviously a gendered bias baked into the name of this column, one that I’ve pondered for a while. In some cases, the word “guy” can refer to anyone, untethered from any specific group or person. I want that to be the case here, where the designation of character actor applies to a wide range of performers. But it’s true that, for reasons historical, cultural, professional, and perhaps incidental, a lot of prominent character actors, at least in the American mainstream, are white dudes.

Often, the more tone-deaf members of the industry will chalk this up to that wonderfully vague word: opportunity. Opportunities to audition, depending on the very specific requirements of the production. Opportunities to know influential people. Opportunities to be rich. Opportunities to mess up and be given a second, third, or fourth chance. Casting sheets don’t just specify age, gender, and ethnicity, but also height, weight, hair color and length, body type, clothing and grooming style, whether or not you own a car, possess a specific talent or know a trade, and, bizarrely, your demeanor (“mean-looking,” “sweet,” “tough," etc). Hollywood has always been superficial and prejudiced, but the granularities can be humiliating. Even the informal Character Actors Dining Society, made up of the likes of Eric McCormack, Alfred Molina, and Richard Kind, seems to somehow only include boys. As Kevin Pollak obliquely said, “We haven’t made any effort to not include women. It started as like-minded actors who admire each other’s work. And we’ve often talked about actresses that we just adore and would love to have join us.”

Eventually, it becomes worth asking what we see in a face onscreen. What mood or personality, class or rank, political affiliation, or religious belief is assumed before an actor opens their mouth. It’s easy for movies to become recapitulations to stereotypes and caricatures, from the magical negro to the shrill, harping housewife. These roles tend to be marshaled in an almost intellectually utilitarian way, providing a shorthand for an audience to decode—narrative economy at the level of platitude. When we talk about an actor “transcending” a bad script, or an underwritten part, what’s being invoked is both a signal to that actor’s talents, but also a reflection of the assumption that a role is, for whatever reason, beneath them.

Which is why I want to kick off this year by talking about an actor who seems incapable of telling the difference between being a bit player and a leading personality, to their immense credit. Tilda Swinton is an actor who seems to relish a big swing, sometimes because the role calls for it and sometimes because she thinks it’ll be fun. Of course, Swinton is also famous. Swinton’s fame is intriguing for the twists and turns her career has taken, from supporting roles in tiny indies like The Limits of Control by Jim Jarmusch, with whom she’s worked with four times, to factory-made juggernauts like Doctor Strange and Avengers: Endgame. It’s not solely this variety that distinguishes Swinton, which is common for any working actor, nor is it any kind of chameleonic talent she possesses for disappearing into a role. More, it’s that Swinton seems uninterested in playing boring people, perhaps because she herself isn’t boring, but also because she claims not to take acting too seriously.

In a Guardian profile from early last year, Swinton dodged the profundity of celebrity—“I don’t have anything to say. I don’t know anything. One thing I do know is I don’t want to even pretend I know anything”—while also revealing a useful philosophy with which to view her work. “I like seeing people for the first time in a film,” she said. “It’s one of the reasons I love documentary. I love seeing people, I’m not interested in seeing actors at all. And the best way if you’re an actor to avoid that annoyance for the audience is just to do one film; then they’ve seen you, they’ve met you, you were interesting and new and they never have to see you again.”

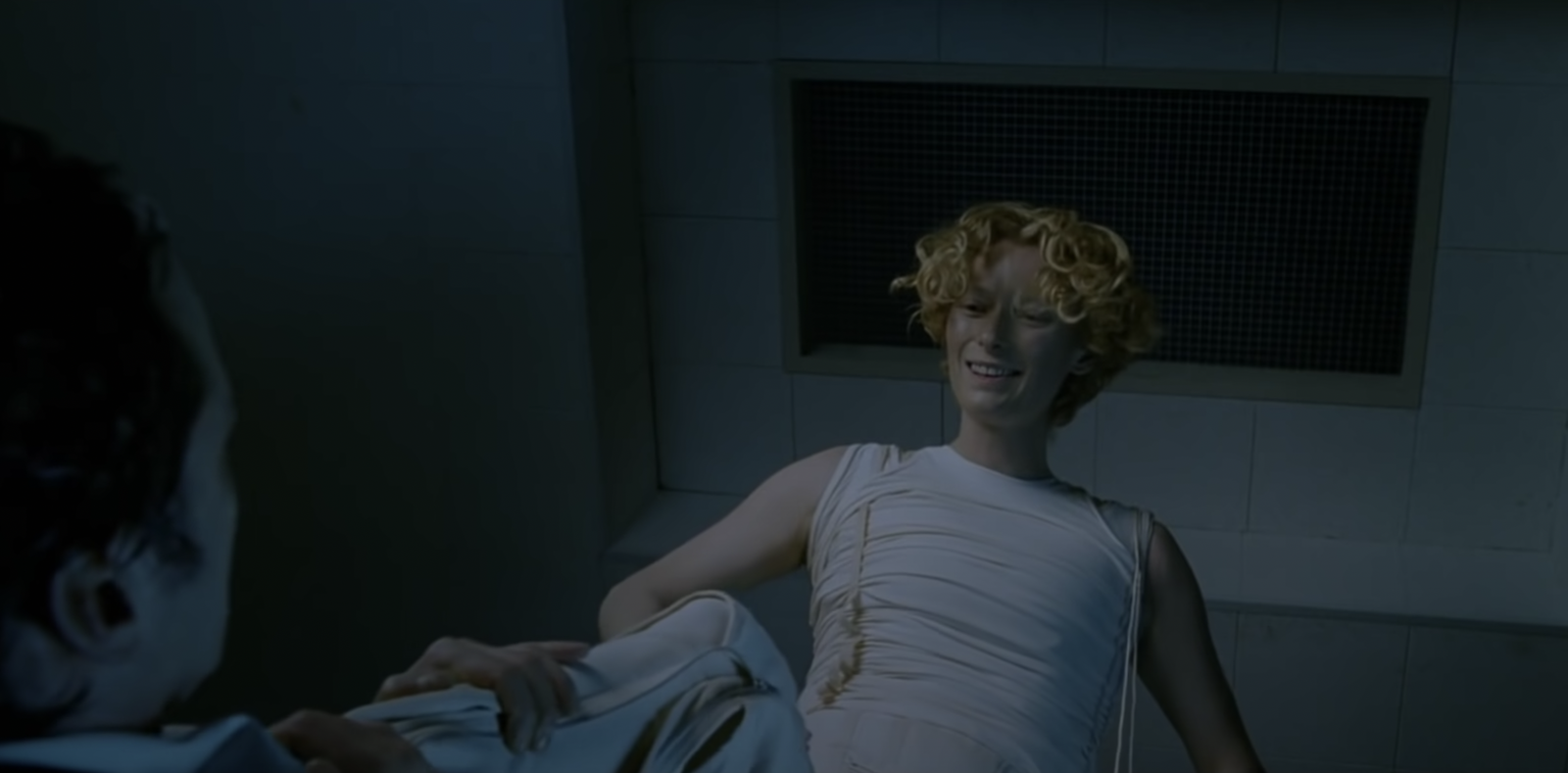

If I’m not always meeting a wholly new person through one of Swinton’s characters, I’m at least watching her attempt to create one. The best of her roles, like her turn as an artist’s mother in The Souvenir I & II, or her Oscar-winning performance as general counsel for a corrupt agricultural firm in Michael Clayton, or even the slickness of her angel Gabriel in Constantine, feel as if they are extant people that are unlike anyone you’ve ever met. This may be the truly defining aspect of Swinton’s style: She is such a singular presence, both physically and emotionally, that her characters often reflect or recreate her individuality. Which is another way of saying that Swinton rarely seems to strive for realism. The buck-toothed, Cockney stooge she plays in Snowpiercer is of a piece with whatever the hell she’s doing with two of the three different freaks she plays in Luca Guadagnino’s remake of Suspiria. These are, in effect, cartoons that nonetheless have something to them beyond their outlandishness. You can sense Swinton’s excitement at being given the chance to disappear beneath false teeth or layers and layers of latex or just a specific accent.

Speaking to IndieWire about her recent film The Eternal Daughter, in which she plays a daughter named Julie and Julie’s elderly mother Rosalind, Swinton said, “I’m not really interested in acting. I’m trying to find the least performative that a person can be. I never like talking about character. That whole vernacular belongs to the theater.” A convenient rebuke against those, like me, who would scry into her filmography for meaning-making crumbs. Except I’m not so much interested in Swinton’s method as I am the result.

Take her part as Elizabeth Abbott in David Fincher’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Swinton appears twice in the film, near the middle and towards the end, over the course of decades. Abbott is a wealthy British socialite alternately bored and thrilled by her marriage to an older globe-trotting trade minister who might also be a spy. As Swinton plays her, Abbott is utterly stylish, with fur coats and magnificent hats, but yearns for someone she desires to notice her. That she is almost comically debilitated by her lack of class understanding is used to her advantage in seducing Benjamin. In one scene, she teaches frumpy sea-faring Benjamin how to properly make tea and enjoy caviar with vodka, all the while watching him closely, holding his eyes, the graceful, deliberate movements she makes with her hands both purposefully studied and self-conscious.

Elizabeth proposes, in an almost business-like fashion, that the two carry on an affair, which her husband seems to make no attempt to discover or question. One night, Elizabeth and Benjamin wander the streets of Murmansk sharing a bottle of vodka, laughing and stumbling as they delight in each other’s company. What is key here is the degree to which Swinton affects the poshness of Elizabeth’s class, with her slightly casual Received Pronunciation and rapturous exhilaration at carrying on an exotic, though not necessarily fraught relationship with a working-class American. There is the sense that Elizabeth is keen to sample everything of life, materially and interpersonally, without any commitment to choosing just one thing. Beneath that, Swinton mines a loneliness that seems to be briefly alleviated by her time with Benjamin. Together, these two withdrawn people draw each other out. The sweetness of this sequence is made more potent by the clarity of Elizabeth’s desire to do something more consequential. Especially because audiences have seen Swinton take on outsized characters before, the normalcy of Elizabeth is naturally imbued with a restlessness, on her part and ours, for a release. The nature of that release is seemingly left unanswered, as one day Elizabeth departs from Murmansk with a note to Benjamin saying “It was nice to have met you.”

One of the joys of watching Swinton is seeing her palpable eagerness to simply play, a sentiment echoed by David Fincher. On the DVD commentary for Benjamin Button, Fincher recalled, “People who are that amazing to look at usually aren’t a lot of fun. And Tilda Swinton is so much fucking fun, it’s just hilarious. She has no preconceived notions. She comes in having charted what it is that she needs to do, but also –I worry about her doing a movie where there’s a lot of stunts because she would be the first person to try setting themselves on fire, just to see what it would be like to act through Zel Gel.” Later in the film, when Benjamin and his lifelong love Daisy are out for ice cream, Benjamin notices a news segment playing on the TV about the oldest woman ever to swim the English Channel. Draped in a towel and sporting a swimming cap, an elderly Elizabeth Abbott walks up to a reporter to give a brief statement about the experience. For a few seconds, we glimpse, through digitally-applied TV static, Swinton in a familiar register, shivering, latex-wrinkled, acting through a physical obstacle that she seems to see as an engaging challenge, an almost perverse sense of zeal emanating from the screen. To the reporter, Elizabeth says, “Anything’s possible,” an unabashed smile on her face, a mixture of relief and gratitude that is as good a description as any for Swinton’s own peculiar, enthralling trajectory.