Emma Chamberlain's most recent YouTube video opens with a montage of archival clips of her trying on outfits, shopping, and then purging her clothes over the years. Despite having, in her estimation, thousands of articles of clothing, Chamberlain says she was never satisfied. Instead, once she had accumulated what she decided were too many clothes, she would do a massive purge of her closet—only to fill it back up again. It's an interminable cycle: Buying a new thing is the answer to your emotional issue du jour, that is until you've unintentionally filled your home with too many things, at which point the only thing you can do to feel better is to purge.

Once Chamberlain had ruthlessly evaluated each of the pieces in her closet, what she was left with, to her surprise, was a sort of capsule wardrobe, a deliberately small, curated collection of clothing intended to be worn interchangeably. That Chamberlain, uber-influencer and proprietor of a 12 million–follower YouTube channel, has gone capsule is indicative of the sustaining appeal of the concept, and I believe indicates an attempt to exert aesthetic control in a time of marked economic and social instability.

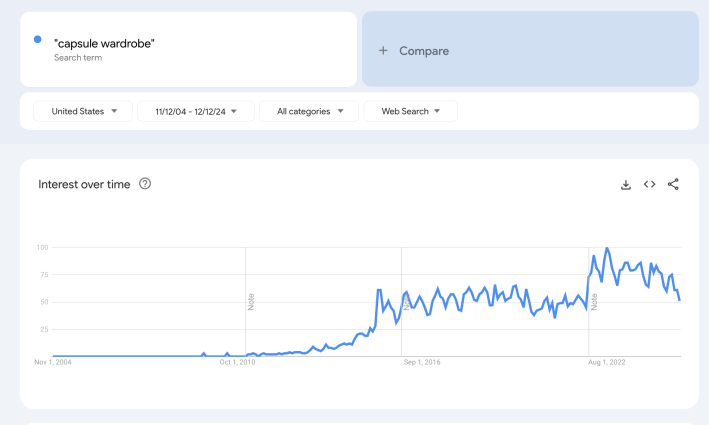

The last decade has seen two pronounced peaks in interest around capsule wardrobes, first in 2015 and then again in 2022.

Like the first gentle high from a joint or the realization that pop music is manufactured, it seems the capsule wardrobe is something every generation must discover on its own. The concept, a small collection of clothing items that can be mixed and matched, dates back to a 1930s creation by designer Claire McCardell.

"In the 1930s, clothes were typically sold as ensembles: Either you bought a one-piece dress, or you bought all the components that made up a look," wrote Nancy MacDonell in the book Empresses of Seventh Avenue. "Faced with Claire's DIY concept, buyers were flummoxed." The pieces caught on though, and McCardell is credited with inventing the American sportswear industry.

The oldest mention of the phrase "capsule wardrobe" I could find in the press, though, was a 1942 advertisement in the Kansas City Times: "Adler's presents a capsule wardrobe at a capsule price. A three-piece skirt, slacks and jacket suit in summer weight men's wear."

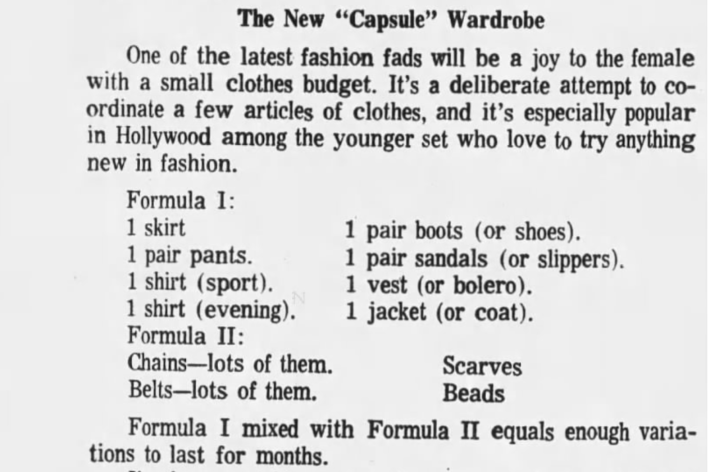

I didn't see mention of what would become the contemporary capsule wardrobe until later. In 1969, a columnist in the Cedar Rapids Gazette called capsule wardrobes "one of the latest fashion fads" and listed out a formula for the ideal wardrobe.

In the 1980s I found a proliferation of capsule wardrobe seminars, like this one in the Battle Creek Enquirer in 1985.

I'm also reminded of Joan Didion's famous packing list, which used to go viral periodically on Tumblr and which still carries with it an air of utilitarianism that prioritizes practicality over form, but somehow still looks cool as hell.

It's important to note that this kind of minimalism is only really an effective aesthetic choice in the context of its opposite, maximalist over-consumption. When you can afford to have more than two pairs of shoes, restraint is an active and chic choice. The effect is different when you can only afford two pairs of shoes, when the minimalism is the result of conditions outside your control. The appeal of this minimalism is in choosing it.

I first learned of capsule wardrobes during their last rise in popularity. In 2016, I got rid of most of my clothes during a fit of Marie Kondo–inspired minimalism. I was stumbling through my early twenties, constantly anxious about who I was, what I was doing, and whether it was all enough. That line from the episode of the Girls pilot—"I have work, and then I have a dinner thing. And then I am busy, trying to become who I am"—perfectly describes that period of my life. Anything that would give me the illusion of control over my life was instantly appealing. I read Kondo's The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up and was convinced of the inherent morality of freeing myself from the shackles of materialism and owning just a few good things. I believed that paring down my wardrobe, especially, would result in a clearer distillation of my identity. I would know myself better, and the world would see me more clearly, too.

But getting rid of my clothes didn't bring me closer to myself. My closet was pleasantly spare, purged of college T-shirts and dresses that a previous version of me would have worn, but I hadn't actually exerted control over the thing that was causing my anxiety: the fact that at 24, I was half-baked as a person and therefore couldn't fully know myself yet, regardless of the size of my closet or its contents.

I was reminded of my own dalliance with minimalism when I saw this video from creator Rian Phin talking about Prada's spring/summer 2025 show, where she quoted the writer Shumon Basar, who asked, "As we become more powerless, do we become more extreme?" She invoked it again when she talked about Chamberlain's latest pivot to minimalism.

Much of online style discourse this year has been centered on extremes: We started the year with the "mob wife" look, defined by fur coats, big hair, red lips, and gold jewelry. It was big, big, big, and a backlash to the "clean girl" aesthetic that had preceded it in popularity, which sat at the other end of the spectrum with low-profile, label-less clothes, neutrals, extremely natural makeup, and slicked-back buns.

As the year wore on, the aesthetic trends continued to ping-pong between all and nothing. In the "all" category: Brooklyn Charm, a Williamsburg jewelry shop where customers can create personalized charm necklaces and bracelets, saw a more than 300-percent increase in sales after videos about the experience went viral on TikTok.

Jane Birkin's messily personalized handbag also became the inspiration for a new trend: Anthropologie started selling bag charms, and women made videos about how to Jane Birkin-ify your purse with accessories from Amazon. Vogue Business called it "chaotic customization," a kind of maximalism centered on the self that, in theory, could not be replicated. In practice, most of this customization is replicable; the charms and doodads are all mass-produced with the goal of providing the illusion of individuality, without the time investment required to build the clear point of view the trend implies.

At the same time, a retrenchment: "Quiet luxury" relied on simple silhouettes and classic colors over logos and prominent brand names. People are increasingly dissolving their fillers to a return to a more natural look. And "low buys" and "no-buys" have become increasingly popular ways for people to renegotiate their relationships with the stuff in their lives.

In a time of inflation, impending climate apocalypse, ongoing genocide, and increasing dread over the forthcoming Trump administration, I find myself adrift on the seas of these cultural extremes, bouncing back and forth between all and nothing in an attempt to exert control over my experience of the world. I may not be the only one. As I was writing this, I was served an eBay ad showing off vintage and secondhand offerings. The ad stars a woman who sits on the pink carpeted floor of a massive closet and opens a box containing a purse that happens to be the perfect item to complete her outfit. She snaps a selfie and then struts out. The woman, of course, is Emma Chamberlain.