In November 2023, Tonya Prewett posted a photo on Instagram of her and her children posing in front of a speaker’s podium. The American and Texas flags stand in the background. The caption read, "A special night with some of my favorite people!"

It looks like a wholesome, family-oriented night, if your family is Southern evangelical, parties with Ben Carson, and marries billionaires. In general though, it's inoffensive. Rich-people stuff.

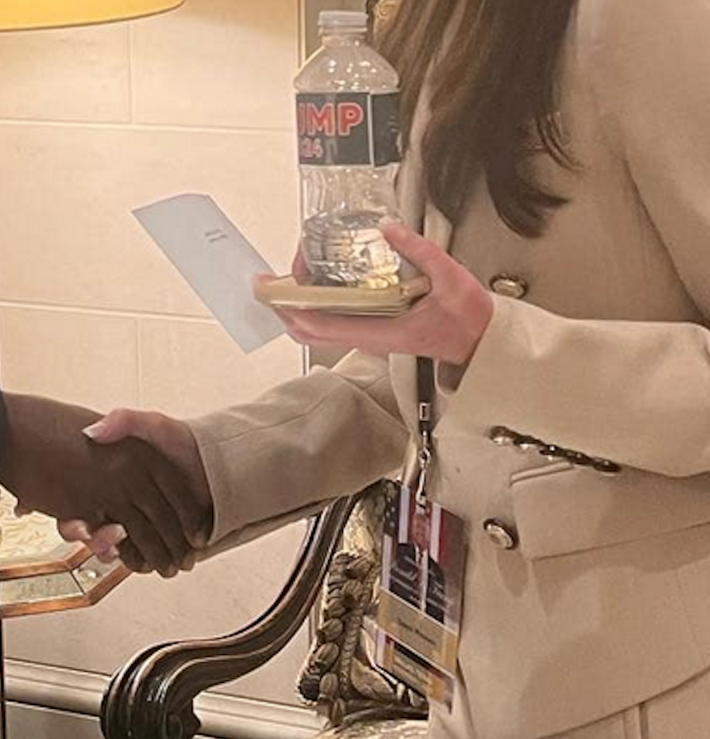

One thing is strange about the photo, though: Prewett appears to be wearing a long necklace that kind of fades into her tan suit. Her daughter, Mallory, also appears to be wearing a long necklace that disappears into her shirt.

That's because the photo is photoshopped. In additional photos posted to Prewett's Facebook page, it’s clear that the necklaces are actually lanyards with Donald Trump's name and face on them.

Two things become clear when you look through the other photos Prewett posted to her Facebook. First: This was explicitly a pro-Trump reelection event. Second: For some reason, Prewett didn’t want to advertise that on her Instagram account.

The billion-dollar elephant in the photo is Tonya Prewett's other daughter, Madison Prewett Troutt, and her husband, billionaire-heir Grant Troutt. Madison rose to fame in 2020 as a contestant on The Bachelor who wore her evangelical faith as prominently as her clumpy mascara. She was a clear frontrunner that season, but she left when she found out the bachelor, Peter Weber, had slept with the remaining two contestants on their overnight dates.

Since then, Madison has steadily built her audience as a Christian influencer, leveraging her 1.8 million followers into customers for her podcast, her books, and branded content. She is one of the most successful Bachelor contestants to have turned their appearance on the show into a full-fledged multimedia career. That this family would be staunch Republicans and ardent Trump supporters is not surprising, but Tonya Prewett's sloppy photo editing betrays a fascinating awareness that, at least in 2023, outspoken Trump support wasn't quite brand-safe.

That reflected the online social climate as it stood then, in the aftermath of Trump’s first term, amid the mainstreaming of gender and sexuality discourse, and with the uprisings of 2020 having brought concepts like critical race theory, marginalization, and systemic violence to bear on normie culture. That moment occasioned a new paranoia and self-consciousness among influencers, perhaps especially those who’d generally avoided politics in their content—many of them white, affluent women who’d never considered politics seriously in their lives. Now their followers were demanding they declare themselves on the systemic oppression of Black people in America, and making a form of activism out of turning against those influencers judged to be reinforcing or reiterating white supremacy.

You may remember what it was like that year, to see what seemed to be every single public figure and business desperately posting whatever they could to prove they were down with the cause, that not only were they not racist, they were actively anti-racist. It was disorienting watching rich white girls scramble to read up on bell hooks in order to preserve their internet careers, but at least they were kind of trying?

Shame is an incredible motivator, but it cannot work as a long-term strategy for inspiring sincere behavior because it is always accompanied by resentment, which can curdle good intentions and ultimately make any efforts toward action untenable. That's one of the reasons the progressive moment didn't stick. Like a January workout routine abandoned three weeks in, a politics built on shame is one that will inspire loud, immediate posturing, but will rarely result in long-term, effective change.

The influencer Danielle Carolan was a student at the University of Georgia when she found herself the target of her own followers; they compiled her racist comments and actions, and sent them to companies that advertised on her YouTube channel and social media. She ended up taking a break from the internet for several months, working with a race consultant who, from what I can tell, gave her some books to read and told her what not to say on record, and posted several apology videos on her YouTube channel. When she did come back, her podcast, Gals on the Go, began featuring a Black-owned business each week.

With time, the temperature on the discourse cooled. At some point, Gals on the Go stopped featuring Black businesses. Carolan moved to New York, continued to work as an influencer, and quietly deleted her apology videos, though snarkers still have the records. She retreated back to what she knows: blowouts, expensive clothes, and documenting other rich people's morning routines.

Election Day came and went, with little more than a vague Instagram story the day after acknowledging "anxiety" and "uncertainty."

Carolan's arc is representative of many other lifestyle influencers. No one is pretending to sleep with their copies of Angela Davis every night anymore. And several have publicly endorsed Trump.

In 2020, Madison Prewett Troutt posted a black and white photo of a march and included the tag #blacklivesmatter. Two weeks ago, she posted a video to her Instagram in which she and conservative author Allie Beth Stuckey explain why a vote for Trump would be a vote for women. The version of Madison that might have hesitated to come out as explicitly pro-Trump only a year ago is gone, and what's replaced her is a version of white womanhood I'm seeing on the move around this country, one that is no longer secretive in its right-wing politics.

To be clear, these women's underlying political beliefs probably haven't changed at all; their explicit Trump fandom might be as much a market decision as their previous superficial adoption of antiracism. The marked shift in how they broadcast their politics, though, is a fascinating indicator of how they perceive the cultural winds to have shifted around them.

This shift I'm noticing is not among the politics buffs and Reagan fangirls, but among the particular population of white women who would otherwise sit these discussions out—many of the same women who felt compelled to post black squares on Instagram in 2020 and buy out their local Black-owned bookstores. The fear of being exposed is gone, and in its place: comfort, even confidence. As annoying as I found the social media antics of 2020, I think I prefer them to this.

Last week, a woman I went to college with announced on Instagram that she voted for Trump. On its face, this is not surprising, as I went to the University of Georgia at a time when it was totally acceptable to reenact antebellum balls and crow "The South will rise again!" at General Beauregard's, the Confederate-themed bar downtown. But this is someone who never participated in the more overt political activities or discussions. Maybe she quietly voted, but she also sat out the heated Facebook debates. I define her less as a stalwart Republican and more as a person who floated agreeably in the cultural waters in which she found herself. She participated in #MeToo in 2017 and dutifully posted #BlackLivesMatter in 2020.

Her online presence is, above all, agreeable. Inoffensive. I've known her for over a decade; she doesn't have a lot of distinctive beliefs or tastes, and I often look to people like her to serve as bellwethers for where the politics of middle-class white womanhood is in a given moment. Which is why it was so jarring to see her celebratory MAGA post: I was surprised not by learning that she leaned that way, but that she felt socially safe to share her political beliefs. Once I'd seen her post, I noticed other political normies coming out as Trump supporters and I realized: These people are not embarrassed to be seen supporting Trump anymore.

This week, Madison Prewett Troutt posted a video on her podcast's Instagram, titled "Handling hate as a Christian."

"It says in the word of God that to be a true follower of Jesus Christ is to pick up your cross, deny yourself, and follow him," she said. "It also promises us that we will be hated because he was hated."

The top comment on the post is from an account called ruthforbearance, and begins: "Really Maddie, who is persecuting you??? You are the most privileged person on the planet. Having people disagree with you on social media is not persecution."