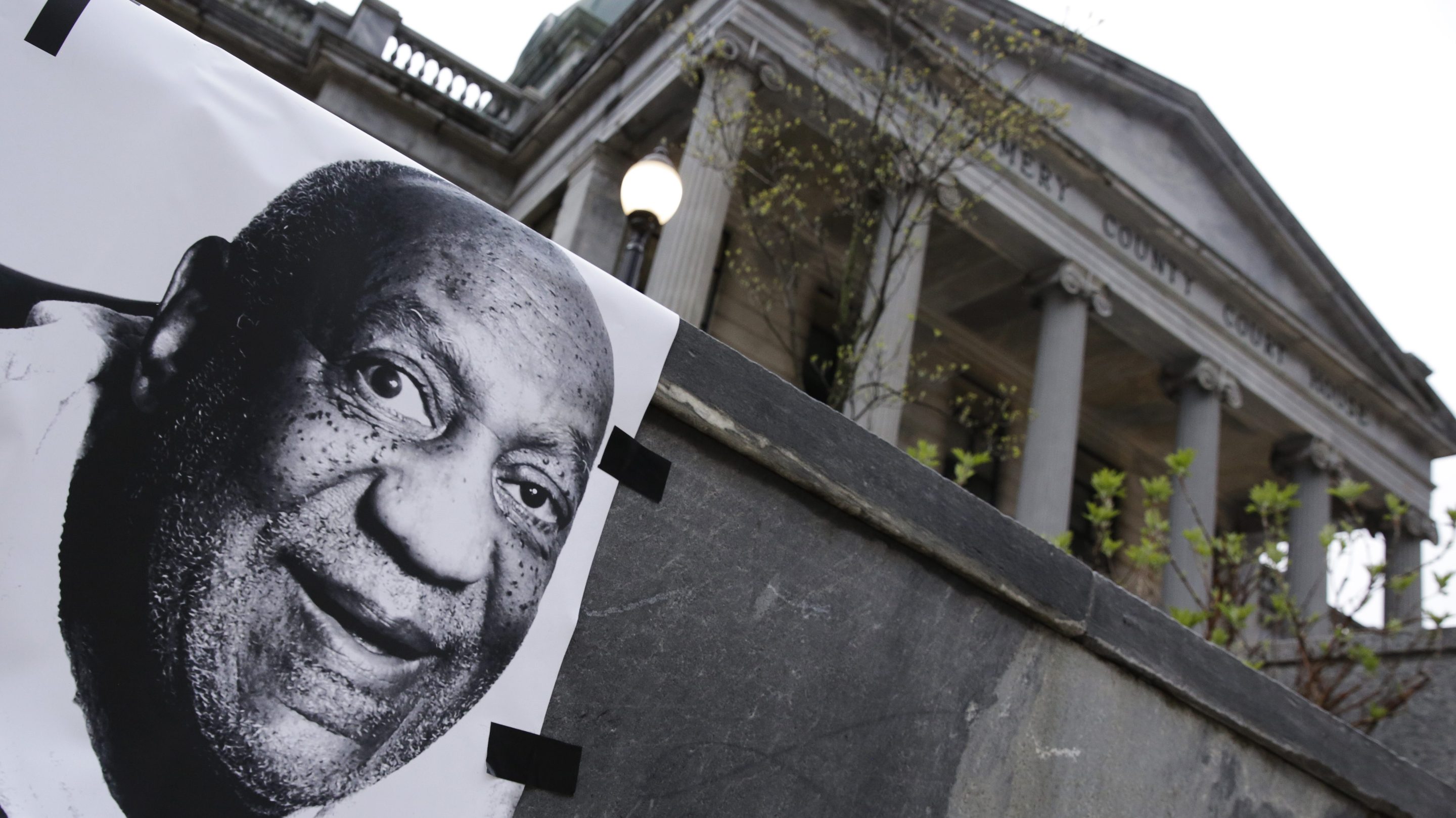

On Wednesday, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that Bill Cosby was no longer convicted of sexual assault. I did not believe it when I first heard it, and perhaps you didn't either because Cosby's conviction on three counts of aggravated indecent assault for the night in 2004 he drugged, then sexually assaulted Andrea Constand inside his home had withstood so many appeals. But nothing is certain in the criminal justice system, especially when you are a person of immense wealth who can afford to pursue every single avenue of appeal, which is what Cosby's lawyers did. This is all perfectly legal—and also very expensive, which is why it is very, very good to be a very, very rich person if you are ever charged with a crime.

That wealth, that power, that stature—he was, after all, creator of The Cosby Show, the man dubbed "America's Dad," a person with much wealth he could legitimately try to buy an entire television network—was what made the conviction seem improbable from the start. Constand first told police she had been sexually assaulted in 2005. Police investigated, and then the Montgomery County District Attorney at the time, Bruce Castor, issued a press release saying he would not be charging Cosby. Afterward, Constand sued Cosby in civil court and settled with him.

Since then, the MeToo movement happened. Dozens of women have said they too were drugged and raped by Cosby. Former Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein has been imprisoned for sexual assault and rape. U.S. presidents have come and gone, including one who said on tape he liked to grab women by the pussy, an attempted insurrection happened on our nation's capitol, as did an impeachment trial, where the president's defense lawyer was none other than Castor. But it's that press release that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court decided to hone in on when making today's decision. Because Castor said he would not prosecute Cosby, Cosby's legal team argued they allowed him to answer questions in his deposition as part of Constand's civil suit. The damning deposition was sealed, but portions of it became public following a legal action brought by the Associated Press, which then lead to the full document becoming public. Once it became public, a new Montgomery County district attorney, Kevin Steele, brought charges and used the deposition in court.

Cosby's lawyers argued that Castor's word and intentions to not prosecute were binding and that no prosecutor after him could bring charges because he was acting, as the majority opinion summarized, as "the state's common-law authority as a sovereign rather than any statutory provisions or protocols." To emphasize the point, Cosby's legal team argued that Cosby and all his lawyers clearly believed this to be true because, otherwise, his lawyers would not have let him answer all those questions in his deposition.

This was enough to sway almost all but one of the judges. Writing for the majority, Justice David Wecht wrote the crux of their viewpoint: "When a prosecutor makes an unconditional promise of non-prosecution, and when the defendant relies upon that guarantee to the detriment of his constitutional right not to testify, the principle of fundamental fairness that undergirds due process of law in our criminal justice system demands that the promise be enforced."

This is a recurring theme in the majority opinion; Castor intended to keep Cosby from being prosecuted forever and, because Cosby believed that to be true and acted in line with that thinking, this is therefore how things should be. There is even a footnote where Wecht goes so far as to say this was not a "routine" decision to not prosecute because it led to Cosby sitting for the deposition, meaning, "Castor's exercise of discretion was made deliberately to induce the deprivation of a fundamental right." Basically, Cosby thought he had immunity and acted as if he had immunity and, therefore, he did have immunity after all. As Wecht wrote, "We now conclude that Cosby's reliance was reasonable, and that it also was reasonable for D.A. Castor to expect Cosby to so rely."

This, therefore, violated Cosby's right to due process and the only way to remedy that, Wecht wrote, was that Cosby "must be discharged, and any future prosecution on these particular charges must be barred."

Nothing better demonstrates the strange legal wrangling that went into this decision than the sheer number of words the court's decision dedicates to a close analysis of Castor's press release. The text of the release itself, what it meant, how it compares to emails Castor sent to his successors, and the definition of the word "decision" are all heavily scrutinized in the court's decision. The ruling includes a footnote, 26 lines long, that just analyzes the context around the phrase "this decision." Eventually this all leads to the court's determination that prosecutors are now sovereigns who can bind all their future successors with nothing more than a press release.

(Wecht wrote the decision, with justices Debra Todd, Christine Donohue, and Sallie Mundy joining him. Justice Kevin Dougherty concurred and dissented, saying he agreed with the majority but disagreed with the remedy, instead thinking a new trial should be ordered, with Chief Justice Max Baer signed onto that opinion. The lone complete dissenting opinion came from Justice Thomas Saylor, who bluntly wrote: "I read the operative language— 'District Attorney Castor declines to authorize the filing of criminal charges in connection with this matter' —as a conventional public announcement of a present exercise of prosecutorial discretion by the temporary occupant of the elected office of district attorney that would in no way be binding upon his own future decision-making processes, let alone those of his successor.")

What goes unsaid in the majority opinion is why Cosby would need a press release to suddenly become a legally binding document, which is that the culture had changed. This was not 2005 anymore, when a woman who said a powerful person had drugged and raped her could be assured she would be dragged through the tabloid slime machine, have every detail of her personal life leaked to eager reporters desperate for a scoop, and even see lies printed as facts. Cosby's problem was our culture had evolved and our shared values had changed. It's always worth remembering that prosecutors are elected, and so it makes sense that a new prosecutor would see the evidence with fresh eyes, and with access to the full deposition, see a strong case and a likely conviction. The evidence did not change. We did.

When I first heard the news today, my heart plummeted. I knew I should not be shocked. I have sat through enough trials to know that our criminal justice system gets as much wrong as it gets right, and it cannot be our sole path to ending violence. Intellectually, I understand the goal is creating a world where the decades of violence that so many women say were wrought by Cosby simply doesn't happen. But for a few minutes, I just had to sit and let myself feel a little heartsick because I am human. Then I reached for my copy of We Do This 'Til We Free Us, a collection of essays by organizer and educator Mariame Kaba about prison abolition, and I re-read what Kaba wrote with Rachel Herzing about R. Kelly and why they would not celebrate the push to imprison the singer because, as abolitionists, another conviction was not the goal.

"Abolition is not about your feelings. It is not about emotional satisfaction. It's about transforming the conditions in which we live, work, and play," they wrote, "such that harm at the scale and as prolong as that perpetuated by R. Kelly cannot develop and cannot be sustained."

As much as today sucks, as much as this news sucks, as much as I hate myself for not being able to think of something more eloquent to say than "this sucks," my aching heart also knows that Kaba and Herzing are right. Regardless of the audacity of judges declaring a press release the equivalent of a legally binding document, ending violence isn't about how many people we can throw in prison. It can't be, because prison doesn't end violence and, as Cosby just showed, the system cannot always be trusted. That's why I know I have to find a way out of feeling heartsick and I will, eventually. Because Cosby wants today to be shouted from the rooftops as a great victory, a cleansing of his reputation, as vindication of himself and his legacy. He wants me to believe the powerful man will always prevail and there's no point in trying to make a better world. But that's false. His legacy is ruined. His reputation is destroyed. We all know who Bill Cosby is. We know how men like him operate now, and that does not change, whether he is in handcuffs or not.

Correction (July 2, 12:17 a.m. ET): An earlier version of this story misstated the name of the Montgomery County district attorney who declined to prosecute Bill Cosby. It has been corrected.