Dear Olivia Rodrigo,

Congratulations on your success. You seem quite talented and people whose tastes I respect enjoy your work. So I hope you take this in the spirit it's meant to convey when I tell you you're wrong about birds.

I came across this bit in the notebook dump of deleted scenes from your recent Rolling Stone interview, and it stuck out to me like a brood parasite in a nest:

“Birds are so foreign to us — there’s not one body part that looks like ours,” she says. “Everyone’s all afraid about aliens and shit. They’re like, ‘What are the aliens going to look like?’ I’m like, ‘We have birds on our planet, and we’re not scared of them. We’re fine!’”

Whether this didn't make the published interview because it's so glaringly wrong, I can't say, Olivia Rodrigo. But I can say it is quite wrong. Studies of comparative anatomy make clear that we share more body parts with birds than with, relatively speaking, almost every other form of life on the planet. They are our cousins, Olivia Rodrigo.

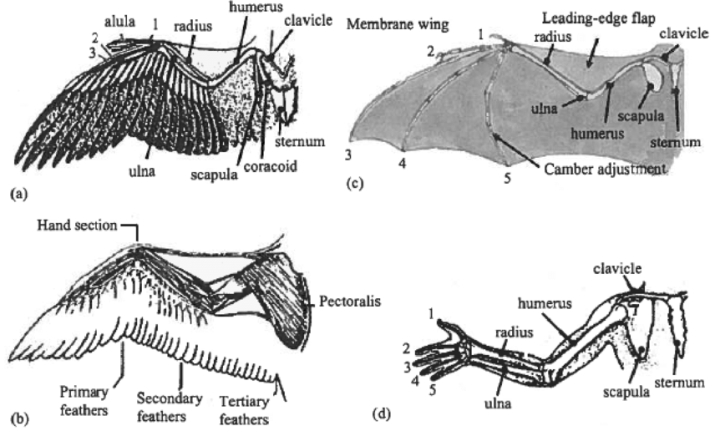

Oh, you absolutely wouldn't think so to look at them. But take the bird's wing, Olivia Rodrigo: it is a human arm and hand, stretched out and adapted, sure, but fundamentally the same in almost every way.

Birds have a humerus, and we have a humerus. Birds' forearms are made up of a radius and ulna, just like ours. Birds' scapulas anchor their arms to their collarbones, just like ours. Obviously, though, there are some differences. Olivia Rodrigo, you seem pretty sharp, so you've noticed that birds have a coracoid bone to help stabilize their shoulder joints, and we do not. We instead have a coracoid process, a small hook-shaped structure that is part of our scapula. The coracoid is essential to flight, and because we don't fly, at some point in our evolution we lost it as a separate bone and subsumed it into our scapulae. Isn't that neat, Olivia Rodrigo?

You've also no doubt noticed that birds have extended fingers—fundamentally the same phalanges we possess—but only three of them. The question of which three fingers birds have preserved has kept scientists busy for a long time. Recent research hints that they are fingers 2–4, index through ring, but that the embryological finger buds follow the genetic program for developing like fingers 1–3 (thumb through middle).

Sorry for the digression, Olivia Rodrigo; I know you're a busy person.

The wing is just one example that proves we're built the same as birds. Don't be fooled by superficial differences. So birds have feathers and we don't? What if I told you, Olivia Rodrigo, that recent genetic research confirms that their feathers and our hair evolved just once, and are essentially the same structure.

When they listen to music—maybe your music, Olivia Rodrigo?—the same parts of their brains light up as ours. In fact, it's possible that birds invented rhythm.

Don't be shocked. We're directly related. Both humans and birds (and all mammals and reptiles and dinosaurs) are amniotes, a clade of animals that emerged some 300–350 million years ago—an eyeblink in geologic time, Olivia Rodrigo. Amniotes split off from the ancestors of amphibians, and were and are distinguished by a number of adaptations for living on dry land, most notably in our skin, respiratory systems, and the makeup of our eggs. With relatively minor differences, their skin is ours; their lungs are ours; their eggs are ours.

Much like how you count 1990s alternative rock among your influences to create music that's related yet distinct, Olivia Rodrigo, we and birds are working from the same evolutionary template to create our own particular forms.

The last common ancestor of humans and birds resembled neither, really—early amniotes were fairly reptile-like. The clade rapidly evolved two variations: synapsids, which would eventually become you and me, Olivia Rodrigo, and sauropsids, which would give rise to turtles, dinosaurs, and that pigeon you seem so concerned about. But somewhere around 312 million years ago, that pigeon and you had the same great-great-etc.-grandmother.

Oh, I saw what you said about pigeons, Olivia Rodrigo.

“Everyone’s like, ‘Have you ever seen a pigeon’s nest? Have you ever seen a pigeon lay an egg?’ And me at 18 years old, I’m like, ‘Wow. I’ve never seen a pigeon’s nest!’”

I'm not trying to synapsid-splain here, but this is a common fallacy. Pigeons are descended from rock doves, which make their nests on high, inaccessible cliffs. Pigeons, living as they do in the city, make their nests in similarly high, inaccessible places; nooks of tall buildings or on fire escapes and air conditioner units. You're not going to find a pigeon nest in the crook of a tree like so many other bird species', Olivia Rodrigo. And if you are lucky enough to have one roost where you can see it, pigeon nests can be quite, uh, minimalist, so you might not even realize what you're looking at. As for why we never see baby pigeons? They stay in their nests until they're fully grown, if all goes right. Consider volunteering at the Wild Bird Fund, Olivia Rodrigo, and you'll see plenty of baby pigeons. They do very good work, by the way.

Look, I get it. You look into a bird's eyes and it can be hard to tell what they're thinking, or if their thought processes are even fathomable. They're not apes or cats or dogs, even closer relatives of ours. But! The tree of life is large, Olivia Rodrigo, with deep roots. We and birds are on the same branch. Their body parts do look like ours. We are not so distantly related as we are to amphibians, or fish, or all the millions of non-vertebrate species. To say nothing of the other kingdoms, the truly unknowable plants or fungi or protists. Those are foreign to us. Birds are family.