Everything about the Europa Clipper mission is huge. Sent to investigate the ice-covered and perhaps habitable second moon of Jupiter, it is qualified by NASA as a Large Strategic Science Mission, conveying with that designation its outsized cost, the peak technical capabilities of its instruments, and the importance of the science it expects to undertake. It is just the seventh planetary science mission to receive the LSSM designation, an elite group that includes landmark missions like Voyager probes and Mars rovers.

The spacecraft itself is massive: the largest NASA's ever built. Twenty feet tall, 72 feet wide when its panels are deployed—about the length of an 18-wheeler—more than 13,000 pounds, nearly half of that propellant, the rest the lightest-weight tech there is. Look at this beast.

Getting this solar-powered monster to Europa will be a trek. Its first scheduled launch date delayed by Hurricane Milton, the Clipper blasted off on Monday from Kennedy Space Center in Florida with more than 5 million pounds of thrust from a Falcon Heavy Block 5, and it will not head directly for Jupiter. Instead it will fly by Mars in February 2025, swooping around the red planet to pick up a gravity assist. Then it'll swing by Earth again, in December 2026, to boost its speed even more. With all that velocity, it still won't get to Jupiter until 2030, and Europa until 2031. Even our tiny neighborhood of space is big.

But the biggest thing about the Europa Clipper—the thing scientists have rationally wondered since discovering Europa's subterranean ocean, and which sci-fi authors from Stanley G. Weinbaum to Arthur C. Clarke have extravagantly imagined—is what it might find.

The Clipper will attempt no landing there, instead entering a complicated orbit of Jupiter that will provide it 49 flybys of Europa, some as close as 16 miles above the moon's surface—more than close enough to sample the plumes of liquid which regularly erupt from it, and which scientists speculate could be an agreeable medium to harbor life.

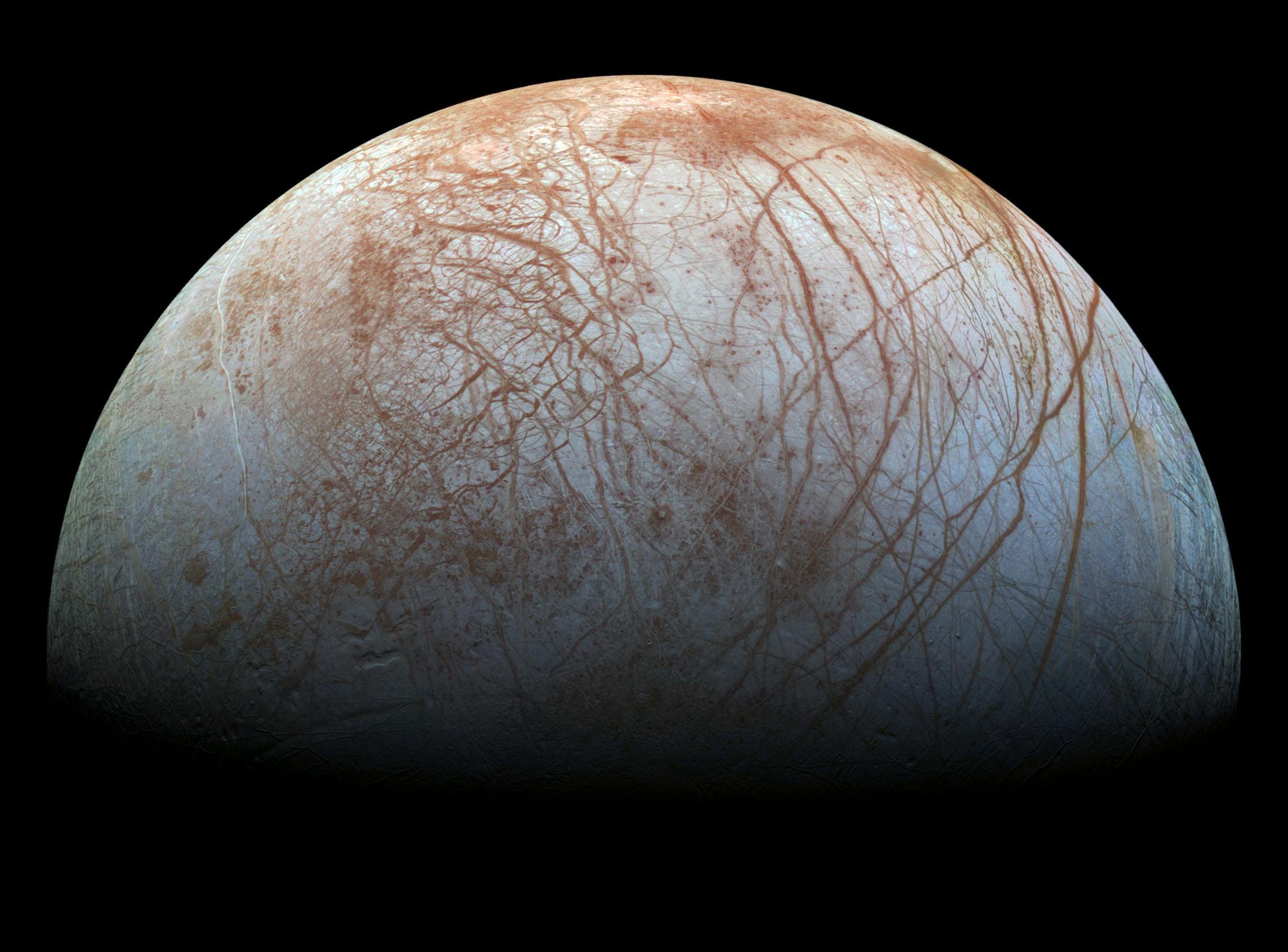

Europa churns. Slightly smaller than our own Moon, it is coated with an icy crust, 10 to 15 miles thick, which floats atop a saltwater ocean itself perhaps up to 100 miles deep. That crust is crisscrossed with lineae easily visible from space. Those are ridges in the ice, formed as the crust cracks, expands, and refreezes in a process that resembles a low-temperature version of our own tectonics. Though with different causes, Europa's surface, like Earth, seethes and breathes and breaks and is constantly reborn.

Europa's crust and ocean sit atop a rocky mantle and iron core that for reasons we don't fully understand—the predominant theory is tidal flexing from the influence of gigantic Jupiter—produces enough heat to keep the ocean liquid. This would necessarily mean hydrothermal vents on the ocean's floor, sending massive amounts of energy upward into the ocean, looking for all the world like undersea volcanoes on Earth. And what do we find around those vents here? Life. Relatively simple, hardy life, but life is a pretty simple equation when you break it down: water, some organic molecules, and an inexhaustible energy source. There's a reason some biologists believe life on Earth may have first formed huddled around the rim of some Hadean "black smoker."

The Europa Clipper will peer at and into the moon, and it will taste it. In ultraviolet and infrared, it will image the surface with unrivaled detail. With magnetometry and ice-penetrating radar, it will plumb Europa's ocean, and even deeper. With mass spectrometry it will sample the dust and vapor of Europa's atmosphere, including those liquid water plumes that spew from the crust, and analyze them for organic compounds. If there is life down there, thriving in the dark and heat at the bottom of an ocean, we may find its signature.

And if we don't, that's fine too. There's incalculable worth in learning all we can about one of our solar system's rarities, in puzzling apart its clockwork just to understand how many unique ways the universe has of making a world. Progress is its own reward, too. When Galileo discovered Europa along with the other largest moons of Jupiter, he thought he was seeing stars. But these four stars were strung out in a line, and as he looked, night after night, they moved independently of the stellar backdrop. One of them disappeared behind the planet; he had become the first to prove that not all heavenly bodies circled the Earth. It will have taken Europa a mere 421 years to go from being a faint dot in a telescope that upended our entire conception of the cosmos to a world so real and tangible that we put a craft within a day's walking distance of its surface.

We're on our way.