Kathy Kohner Zuckerman was at home in the Pacific Palisades, her husband Marvin working on the computer in his office, when a neighbor came pounding on their front door.

“Kathy, get out! Get out now!”

It was mid-morning on Jan. 7, and Kathy could see—and smell—the black smoke up in the hills above the home on Marquette Street that she and Marvin had shared for 60 years and where they raised their two sons. Her neighbor grabbed paintings and photographs off the wall and deposited them in the back of Marvin’s car. Kathy brought in two suitcases from the garage, and threw in papers that she’d saved over the years, photo albums, and a few books signed by her father. She also rescued the seminal diaries she kept as a teen, when her life as a pioneering surfer-girl nicknamed “Gidget” forever changed the course of surf culture.

Marvin took four books, a pair of pants, some toiletries, and medicines. “He didn’t take it real seriously,” she deadpanned.

Although she is reluctant to drive these days, Kathy took her own car and followed Marvin as they drove off their dead-end street. She parked the 2002 Mercedes on a wider street and joined Marvin in his car. It took them an hour to reach Sunset Boulevard, a trip that normally takes about two minutes, and then they navigated down to Santa Monica and joined the long lineup of cars and people waiting to check into the Fairmont Hotel.

They stayed there for most of January, with the exception of two nights when they were evacuated to another hotel because of a fire threat. Her sons and their families came to celebrate Kathy’s 84th birthday with a festive brunch at the Fairmont; that was also their anniversary date, their 60th.

That brief ray of happiness was needed. Their home was destroyed, as was the house next door that they’d bought and rented out to tenants. Fifteen of the 16 homes on Marquette Street burned to the ground. The Mercedes survived.

“That’s the story,” Kathy said, curled up on a white couch in the cozy Santa Monica short-term rental that her daughter-in-law found for them. “It’s sad. It’s just so sad. We lost our home. Everything in it. What can you do? What can you do?”

She sipped hot tea, a bright tropical flower tucked behind her left ear. Marvin, about to turn 93, graciously chatted for a few minutes before he left to shop for a new computer. “We’re safe and that’s the main thing,” she continued. “It’s unbelievable how people have been so supportive. All the clothes I’m wearing—this blouse, the leggings, this [pendant]—people donated. ”

With a toothy grin, the bubbe from West L.A. toggled to her sea-sprite alter ego Gidget, she of the boundless energy and can-do demeanor. “The brassiere is from Nordstrom,” she exclaimed.

Kathy Kohner Zuckerman holds a unique place in American pop culture. She’s a surfing icon, a Jewish icon, a Southern California icon, a feminist icon. And, as the title of a documentary about her life put it, she’s also an accidental icon.

Her parents came from Bohemia, part of the Austro-Hungarian empire in what is now the Czech Republic. Her father, Frederick, earned his PhD from the University of Vienna. He became a successful screenwriter who realized early enough that as a Jew working in Nazi Germany, his days were numbered. He left after noticing that Joseph Goebbels was scrubbing the names of Jewish writers from the credits of their films.

Frederick, with his wife Fritzie and their daughter Ruth, followed his older brother to Hollywood. Paul Kohner was a successful producer-turned-agent whose lengthy list of A-list clients included Greta Garbo, Billy Wilder, and John Huston. (Kathy’s cousin is the actress Susan Kohner, whose sons are directors/screenwriters Chris and Paul Weitz of American Pie fame.) In so doing, they joined the sizable exile population of artists and intellectuals fleeing the rising tide of fascism for the ocean breezes and rustic canyons of the so-called Weimar on the Pacific. The Kohners settled in Brentwood. Frederick met with some success, sharing an Academy Award nomination for Mad About Music. He also co-wrote the screenplay for Utopia, the final screen appearance of Laurel and Hardy.

In 1941, as World War II engulfed Europe, Kathy was born in Los Angeles. Her neighbors thought her something of a tomboy. She learned to ski in Sun Valley, Idaho, meeting a young filmmaker named Warren Miller while he was shooting his first 8-millimeter ski films. According to the Los Angeles Times, “She grew up here as the tiniest girl with the biggest heart. She could run faster and knock a baseball farther (yes, sometimes through a window) than any of the children.”

Her introduction to beach life came as the Kohners and their fellow expats spent weekends picnicking and lounging on the sand in nearby Malibu. “We’d been going to Malibu since I was 3 years old,” Kathy said. “Malibu had a certain cachet because the Hollywood people would go there and hang out on the beach.”

She was displaced from Southern California for two years while her father took screenwriting jobs for producer Artur Brauner in post-war Berlin. She used the opportunity to learn German and to ski at Klosters in the Swiss Alps. When the family returned to Brentwood, Kathy struggled to find her place among her peers at Uni High in West L.A. Until, that is, the summer of 1956.

Dwight Eisenhower was coasting to a second term in the White House. The Cold War was heating up. African Americans in Alabama were staging the Montgomery Bus Boycott to protest against segregation. Mickey Mantle was cruising to a Triple Crown in the Bronx. Elvis Presley’s first album was climbing the charts. Except for Elvis, 15-year-old Kathy was preoccupied with other matters—specifically, surfing and boys, both of which she found in Malibu.

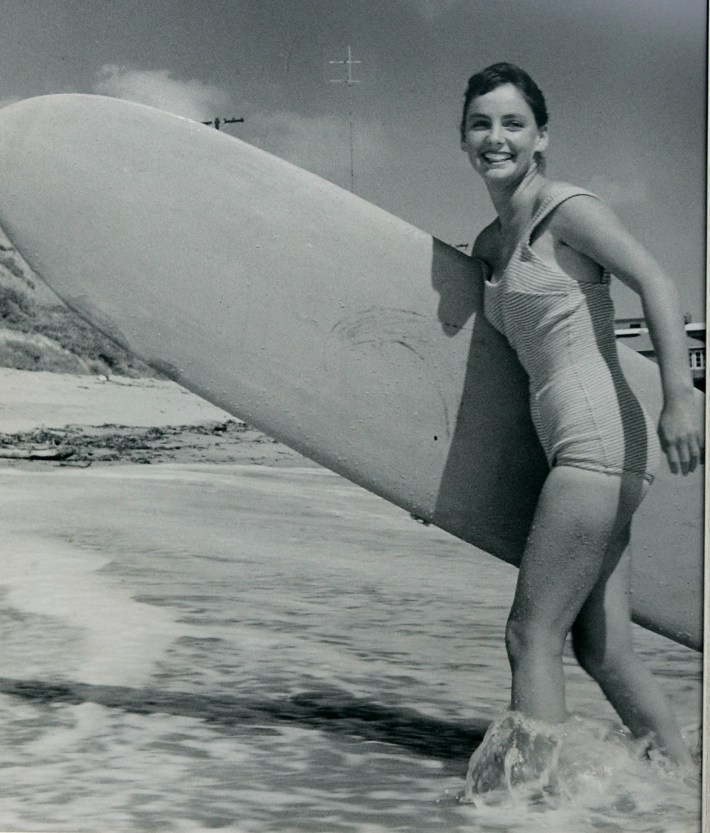

Kathy had a “major crush” on a surfer named Bill Jensen, she remembered. “A biiiig crush.” She took to stuffing tissue paper in her bathing suit to enhance her figure. Kathy's mother would drive guys from the neighborhood to Malibu, their longboards sticking out from the jumpseat like sailing masts. “That’s what I wanted to do,” she said. “I wanted to ride a surfboard.”

Her timing was exquisite. The ancient sport of Hawaiian royalty was making its way across the Pacific and attracting a cult following among young converts who rebelled against conformity by chasing endless waves. A new generation of lightweight, relatively inexpensive foam boards was replacing the 90-pound, solid redwood behemoth longboards that Duke Kahanamoku, the godfather of modern surfing, had wielded on Waikiki Beach, enabling even someone as diminutive as Kathy (barely five feet tall and maybe 95 pounds) to paddle out.

She wasn’t the first wahine to surf, but at the time very few women dared to penetrate the almost exclusively male community. “I’d say, ‘I’m not bothering you guys,’” she recalled, “and they’d say, ‘Yeah, but you’re still breathing.’”

Kathy persevered and purchased an 8-foot-6-inch, 22-pound balsa board from a shaper named Mike Doyle, who like many of the young men Kathy encountered at “The Bu” were destined for fame within the surfing world. “He brought it over to me in his Messerschmitt and I paid him $35,” she said. “There was a totem pole painted on the front of the board. It was beautiful. I wish I still had it.”

Nearly every day she recorded her progress and thoughts in a diary using the vernacular of the beach: “bitchin’,” “jazzed,” and “bite the rag.” One entry read: “Boy was it a fabulous day today. Everyone was at the beach. I rode a wave today and everybody saw me.”

What captured her imagination was the louche lifestyle enjoyed by the beach bums. “There was this guy, Terry Tracy, and he lived in a shack!” she said. “He had a roommate named Harry Stonelake the first year. And I was like, oh my god, these guys live at the beach and they stay the night. Don’t they have a mom and dad? Don’t they go home? It was like an awakening to economic and social differences for me.”

Everybody at the beach had a moniker. “There was Tubesteak [Terry Tracy], Lord Blears [who moonlighted as a pro wrestler], Thrifty Phil, The Fencer, Scooter Boy, Da Cat [Mickey Chapin a.k.a. Miki Dora].” Kathy knew that to be considered a member of the tribe, it was vitally important to have a nickname of her own. Soon enough, the tiny teen who brought peanut butter and radish sandwiches to the appreciative crew was dubbed “Gidget,” a portmanteau of “girl” and “midget.”

“I was so happy to get that name,” she said. “I was like, 'I’m Gidget!'”

One day, Kathy announced that she wanted to write a book about her surfing experiences and the characters she was meeting at Malibu. “Dad said, ‘You’re not a writer. You keep a diary, but I’m the writer. So, tell me everything.’”

She proceeded to do just that. Her father took careful notes, even going so far as to listen in on Kathy’s marathon phone conversations with her friends. The 51-year-old Frederick then translated her musings and flirtations and surf exploits into a novel that he banged out in three weeks. Almost instantly, it was sold to G. P. Putnam’s Sons and published in 1957, accompanied by a Life magazine pictorial spread featuring father and daughter.

In Gidget: The Little Girl with Big Ideas, a teenager named Franzie—also nicknamed Gidget—yearns to surf and yearns to fall in love. Written in the first person, much of what happens to Franzie is taken from Kathy’s life, with artistic and dramatic license sprinkled throughout. Gidget’s got the hots for a surfer named Jeff (nicknamed Moondoggie). The boss surfer of the crowd, nicknamed Kahoona, lives in a shack and is surrounded by male cronies who live for surfing, beer, and girls.

On the night of the big luau at the beach, the Santa Ana wind is blowing. After some of the raucous partygoers light torches, a brushfire erupts in the hills across the highway. “In Southern California all that’s needed to start a first-class holocaust is one small spark,” Gidget wrote, presciently. “We had learned this in school and now I looked at a genuine life class demonstration.”

A burst of rain—“water from heaven,” according to Kahoona—extinguishes the fire and prevents catastrophic damage. By the book’s end, a now-wizened Gidget, going on 17, concluded: “All things considered—maybe I was just a woman in love with a surfboard.”

Gidget would probably be marketed as a YA book today; in 1957, it was well-reviewed and secured a spot on numerous bestseller lists. “Gidget is a pleasant novel about a nice—for a change—teen-age girl and the summer she spent with a bunch of surf bums,” according to The New York Times. The Los Angeles Times praised the “unquestionably authentic dialogue” and called it “a 15-year-old American answer to Françoise Sagan,” she of the très scandalous Bonjour Tristesse.

Columbia Pictures snapped up the film rights. Directed by Paul Wendkos and starring Sandra Dee (Gidget), James Darren (Moondoggie), and Cliff Robertson (Kahoona), Gidget was shot at Leo Carrillo State Beach, up the Pacific Coast Highway from Malibu, and released in 1959.

It didn’t seem to matter that the movie dumbed down Kohner’s nuanced novel, as Hollywood is wont to do, and that Dee’s bland innocence erased everything that made Kathy so appealing. Nor did it matter that the cinematography of the surfing scenes was laughably cheesy, or that the trio of songs awkwardly inserted into the film was equally lame. The film was popular among teens because it goes down as easily as a peanut butter and radish sandwich: buff, tanned bodies; surf, sun, and sand; the excitement and heartbreak of teenage love; the joy of catching waves. Gidget comes across as a rebel for barreling into the boys’ club, although her rebelliousness is wrapped in sun-spackled optimism, in contrast to works from the same era that depicted the underbelly of American youth culture: Catcher in the Rye, The Wild One, Blackboard Jungle, On the Road, Lolita.

Frederick Kohner went on to write five original Gidget novels and two novelizations of films. “My father hit the jackpot, he didn’t have to write any more screenplays after that,” Kathy said. There were numerous Gidget movie sequels and TV movies, as well as TV shows, including an ABC series starring Sally Field that lasted one season and a syndicated sitcom entitled The New Gidget. He wrote several more books, including one about his brother Paul, before his death in 1986.

The ubiquitous popularity of Gidget marked what the writer Jamie Brisick has called “an inflection point”: Surf-riding was poised to transition to surf lifestyle, from a sleepy pastime to a billion-dollar mainstream commodity, a trend that the hardcore band of surfers stretching from Waikiki to Malibu to Freshwater decried but were powerless to prevent.

In Gidget’s wake came surf fashion, surf music, surf movies. Filmmakers Bud Browne and Bruce Brown began shooting their quirky documentaries featuring Woodies and endless summers, and John Severson published the first issue of Surfer magazine. Dick Dale wailed on his guitar at the Rendezvous Ballroom, while the Chantays were recording “Pipeline.” The Beach Boys and Jan and Dean were harmonizing in the studio, while Hollywood swooped in to make awful beach-party movies starring Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello.

And, arguably, the two people who most influenced that revolution were a wistful teenager from Brentwood and her Jewish-exile-with-a-doctorate father.

After the publicity binge for the first book, Kathy avoided the spotlight. She went to Oregon State University, where she babysat for her English professor Bernard Malamud’s two children and went to poetry readings. She spent the summer of 1959 in Hawaii, where her Dale Velzy surfboard went missing. Then she briefly joined the Peace Corps before she met Marvin, a Bronx-born scholar nine years her senior, at a party in Topanga Canyon. They went out on a date and she told him that she was Gidget. “What’s Gidget?” he asked.

Films like Gidget were “not even on my radar,” Marvin later said, because he was too busy watching Ingmar Bergman movies.

They married on her birthday in 1964, the same year they bought the ranch home on Marquette Street. Marvin taught English and Yiddish at Los Angeles Valley College, before becoming Dean of Academic Affairs. After a brief stint as a substitute teacher, Kathy concentrated on raising their two sons. (One son is a sociology professor at Pitzer College; the other is a producer and president of Virtual Pitch Fest.)

By then, she’d dropped out of surfing, leaving Gidget behind. “That was another life,” Kathy said.

The millennium marked a rebirth of the Gidget saga. Surfer magazine ranked Kohner Zuckerman seventh on its list of the 20th century’s most influential surfers. (Duke Kahanamoku topped the list.) Two years later, after a push by the writer Deanne Stillman, Putnam’s re-issued Gidget, with a foreword by Kohner Zuckerman. Meanwhile, Francis Ford Coppola co-wrote Gidget: The Musical, in a stage adaptation that was performed in 2000.

Kathy decided to re-enter the surf world and reconnect with her Gidget-dom. She paddled out on special occasions, and spoke about the book at schools and on TV shows like Good Morning America. She took a gig as a greeter at Duke’s on PCH in Malibu, part of the umbrella-drink restaurant chain named in honor of Kahanamoku. There, she serves as “the ambassador of aloha” three days a week, spreading cheer among customers and staff alike.

“I started a new life,” Kathy said. “I blossomed because it was fun, a reawakening. I made every effort to go out and speak about the story of Gidget.”

She’s also been working with author Ken LaZebnik to turn her original childhood diaries, the pages now well-worn and the scribbling faded, into a new book. “They’re girly-girly, but they’re mine,” she said. “They are the real Gidget diaries.”

Duke’s is temporarily closed because of the Palisades fire, and Kathy admits that she has her dark moments thinking about what she calls “the little things.” A portrait of her grandmother? Gone. Dishes her mother dragged over from the old country and only used for special occasions? Gone. Her fabulous postcard collection? Pieces of jewelry? Marvin’s books—what Kathy called “the library that never stopped”? All gone.

Then the indomitable spirit of Gidget kicks in. “It’s like my friend said to me, ‘You didn’t pack up and then get shipped to Auschwitz. You got packed up and you have a nice new surrounding and a lot of people are comforting you, and Santa Monica is really nice.’”

After the fire, an article in the Los Angeles Times indelicately announced: “Gidget Goes Homeless.” The response was overwhelming: Hundreds of texts and emails poured in from the surfing community, offering help, shelter, books, clothing, and, yes, plenty of aloha.

Neither she nor Marvin have gone back to Marquette Street. “It’s all ash there,” she said. “I don’t want to put a hazmat suit on. I don’t want to breathe anything toxic. Forget it right now.”

Her laugh returns. “Ashes to roses,” she said. “That’s what I want: roses. I want to see roses for Valentine’s Day.”

The Santa Monica rental will need to be vacated eventually. Kathy and Marvin are still figuring out their next move. Do they rebuild? Do they buy another place? Do they find a furnished rental?

“We’re survivors, Marvin and I,” she said. “You just gotta move forward. Just like when you’re surfing. There’s always something outside. What’s outside? It’s that next wave.”