One of the scariest pitches I've ever seen at a baseball game came out of the hand of Minnesota's Hansel Robles during the seventh inning of Twins-Tigers on Saturday night. When Detroit's Eric Haase led off the inning and faced down the veteran reliever's very first pitch, he took a 95 mph fastball right to the dome, causing a sound comparable to that of solid contact to reverberate around the ballpark.

Thankfully, the batting helmet did its job, and the Tiger rookie popped right back up off the dirt. But even so, Haase would go on to be removed from the game for a pinch runner, and he would sit out Sunday's series finale. When Robles came into the league in 2015, it took him over 117 innings to hit his first three batters. But this season, it was Robles's third HBP in just 41 innings.

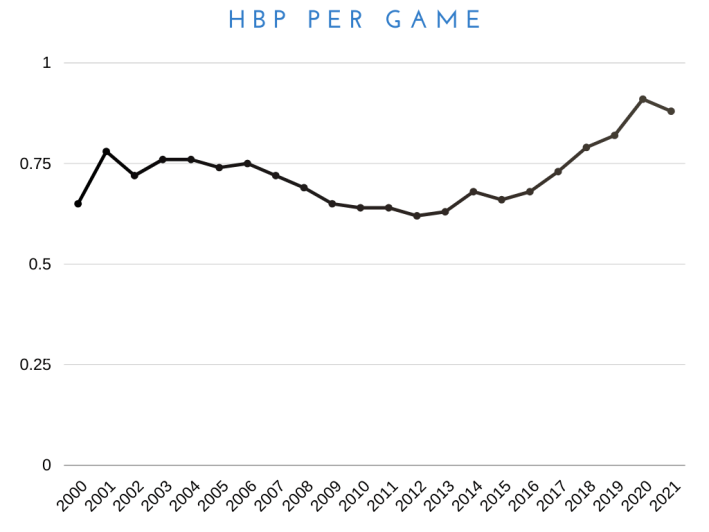

If you, kind baseball watcher, feel as though you've been seeing a rise in HBPs lately, your instincts are correct. The Haase incident, coupled with Nathan Eovaldi hitting two Yankees in a row around the same time on Saturday, prompted me to do a bit of graphing, and the results confirmed my suspicions that hit batters are on the rise. The 2000 MLB season averaged just 0.65 HBPs per game, while in 2021, we're getting 0.88 every contest. The four highest seasons for HBPs in the millennium have been each of the last four seasons, with 2018 (0.79), 2019 (0.82), and 2020 (0.91) all setting new highs. (For what it's worth, we're all the way up to 0.95 HBPs per game since the umps started cracking down on sticky stuff, but that's still a pretty small sample size.)

As a result, injuries from pitches or really close calls have been frighteningly regular as of late. In 2021 alone, we've seen Bryce Harper get hit in the face with a 97 mph fastball, Kevin Pillar suffer multiple nose fractures from a fastball in the same spot, Willie Calhoun get a forearm fracture, Ronald Acuña leave a game after taking a 98 mph pitch to his hand, Chad Pinder get hit in the head, Carlos Correa exit a game after taking one to the knee, and Aledmys Diaz departing due to one to the hand, among others.

The most obvious culprit here is the velocity increase, and corresponding lack of control. From 2008 to 2020, the average MLB fastball rose from 91.7 mph to 93.7 mph, and particularly in the highest percentile of flamethrowers, there are more guys touching triple digits than ever before. Because these pitchers have overpowering stuff, their command is valued by their teams less than ever (there's also more than half a walk more per game than there was a decade ago), and because of the nature of the massive modern bullpen, more and more young pitchers with strong arms are receiving their ticket to the big leagues without a fully polished arsenal.

“I just think with the velocity that is going on with pitchers today, and them pitching up, the ball sometimes takes off a little bit more because of the spin rate up there," Phillies manager Joe Girardi told the New York Times in May. "I think we worry about up and down more than we do command to the corners.”

Pillar, after his injury, had a similar take:

“It’s a pretty simple answer: I think velocity has become the primary factor in determining whether a guy can pitch at the highest level of baseball, as opposed to pitchability,” said Pillar, who was placed on the injured list Tuesday and will need plastic surgery on his nose.

“You’re seeing more and more guys that throw hard and teams are hoping that they could develop pitchability and control and a secondary pitch. You’re not seeing as many guys that throw in the lower 90s or 90 that have very high pitchability with multiple pitches to get guys out."

The New York Times

Other factors are at play here—Tom Verducci and Bob Melvin have both noted that padded-up batters are more likely to stay in the box and take a hit—but what's especially bad about the increase of wild fastballs up and in is that they make the HBP a much more dangerous occurrence than it already is. Guys like Pillar are a testament to that, and I shudder to think what might have happened if Haase's helmet had slipped off his head as he ducked down on Saturday.

In 1920, Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman was killed after he was hit in the skull with a pitch, becoming the only MLB player in history to die from injuries sustained in a game. In the ensuing years, Willie Wells of the Newark Eagles was knocked unconscious by a pitch and Hall of Fame catcher Mickey Cochrane had his career ended by a ball to the head. Very slowly, over the course of several decades, the batting helmet became more and more of a common sight until it became universal after the 1979 season.

The helmet and the other protections hitters now wear do a great job of preventing serious injuries, but they are not 100 percent effective, nor should they be relied upon as a sole defense against the rise of the hit batter. To keep hitters safe in an increasingly unsafe box, MLB could take steps to reverse the trends we're all seeing. A simple solution, off the top of my head, would be treating the HBP like a flagrant foul in basketball, leading to an automatic ejection for more than one, or even an ejection right away for hitting a guy high. But taking away a pitcher's option to work inside probably won't fly. There is also the idea that an HBP could be worth two bases, instead of just one, but there's no real mainstream support within the game for that, either. What worries me, particularly if the trend of hit batters continues to rise, is the possibility that baseball won't do anything about it until it's too late.