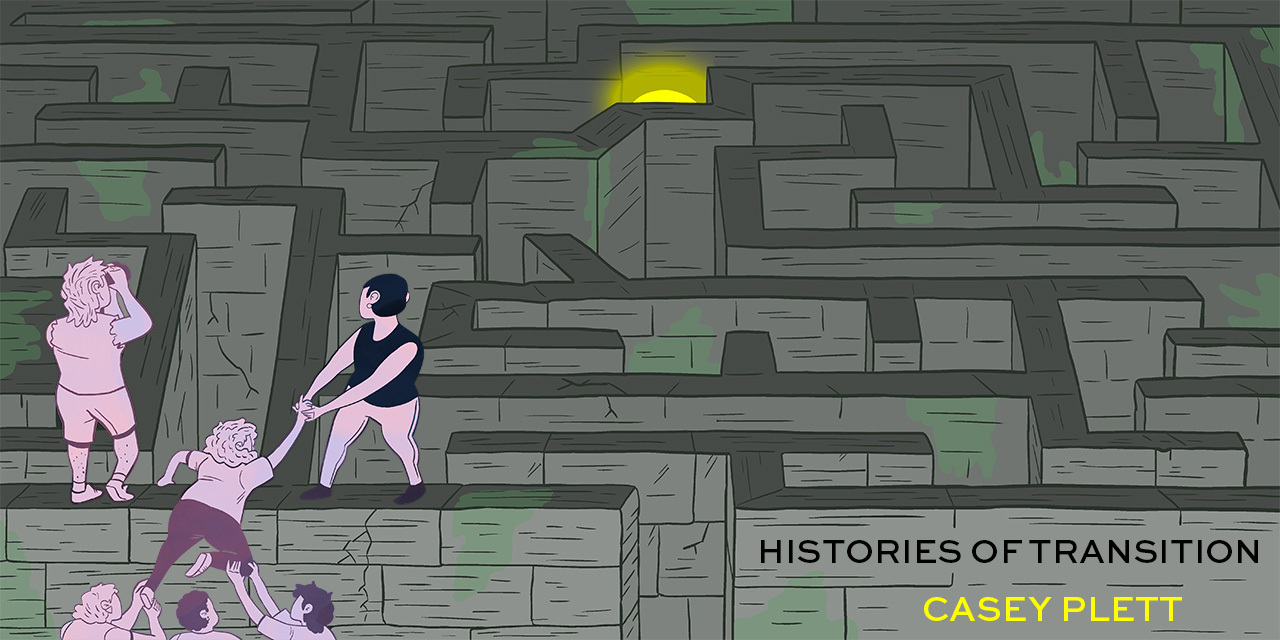

This is the start of Histories Of Transition, a new series spotlighting the experiences of trans people as they've worked to exist within structures that don't want them to.

When my first doctor in 2010 put me on a hormone replacement therapy regimen—estrogen and a testosterone-blocker—he told me, verbatim, "We don't actually know what these will do to you. You could die."

He was wrong. HRT, as we like to call it, is astoundingly safe. I've been downing the stuff 13 years now, and I've never had any health problems related to it, not one, and neither have the countless trans people I've met since. But this doctor said it authoritatively, and I believed him. This was a (supposed) trans health expert in NYC—a guy who, I believed, Knew How to Do Things Properly.

I came to this man because he was recommended to me by the main city LGBT health clinic, which couldn't give me services itself because I had health insurance. That health insurance had just switched over to cover hormones; I was going to grad school and their ban on “gender identity disorder” coverage had been partially struck, just as I'd finally, doggedly decided I had to get on estrogen. World's greatest serendipity, eh?

My school's doctors, however, didn't know anything about trans care and I guess they didn't want to learn. HRT regimens aren't complicated, but I think they were scared of it. I sat in an administrative office while we called that LGBT health clinic together. I was 23 years old and sitting on speakerphone with this middle-aged guy who ran the school's benefits. The clinic worker told us to go see this one doctor downtown. They said he was a trans health expert.

I didn't do any research about this doctor. At that point I don't think I really cared. I'd been hemming and hawing about HRT since I was 19, and at that point, I think I was willing to trudge down whatever corridors had a dim arrow reading ESTROGEN THAT WAY until I had a pill bottle in my hand. I was flabbergasted that my insurance was going to cover it at all. I mostly just felt lucky.

The doctor's office was in Tribeca. He had a tiny waiting room with a TV showing clips of then-Attorney General Andrew Cuomo talking to the press about his run for governor. The doctor shook my hand when I stepped into his office, which he would do without fail at every appointment. He was young and square-jawed and extremely good-looking. I think he was in his 30s. I sat down in his wood-paneled office and nodded solemnly as he told me I might die. It's strange to think of how blasé that moment felt.

After I graduated, I had to self-med for a year—I moved back home and got on my parents' health insurance, which still had its trans ban in place, and there weren't really doctors to see in town for trans stuff anyway. But by then I'd been on HRT for two years, and I'd known enough other transsexuals who didn't have the luxury of bloodwork and doctor check-ups. I'd also read enough to know trans lady HRT was basically as safe as hormonal birth control for cis women—safer, actually, by some measures. So the self-medding didn't bother me.

Then I went to live in Canada for a while, where my home province had just started covering trans care, and I've been fortunate enough to have HRT coverage ever since, even once I came back to the States. I still dutifully go for bloodwork but honestly it's mostly just to keep my current doctor happy, a habit more than anything. When I temporarily had shitty ACA insurance last year, I considered refusing the bloodwork just because the labs were getting expensive. I'd rather not have to self-med again, but if I had to, the only thing that'd really worry me is precarity of supply.

Back in the late 2000s, when I was living in the Pacific Northwest, pretzeled up in knots over the Do I?!? question, most of my info came from old websites, rando community advice on message boards, and a couple terrible local therapists who supposedly specialized in “gender identity.” One of them said, “Doctors are not interested in creating freaks,” when I asked if I could take hormones but not get surgeries. She was also wrong. But I didn't really know trans people in real life. I definitely didn't have trans friends. So I believed her.

Some of the internet trans women I read back then were big on this idea of seriousness—that you should only transition if the alternative is literal death. That's definitely reality for a lot of us, but I've also since learned to appreciate that you can transition even when literal death is not on the line, and that we should have the right to do so whatever our individual circumstances might be.

There's one experience from that period I keep thinking about. In 2008, I went to see a doctor far out in the suburbs. Her website was devoid of transgender anything, and the design was stuck in 1998—scrolling text, visit counter—but the internet message boards said she was a good doctor for hormones. Funnily enough, I still wasn't even ready to take the stuff. I just wanted information! I think I wanted to talk to a real-life human who wouldn't tell me I was a freak. (It didn't even occur to me then to check if my insurance would cover the visit, which it did not.)

I put on a dress before heading over. I did this because of what I understood then from the websites and the rando community advice—that there were these archaic rules about needing to demonstrate “real-life experience” in your gender before they let you take hormones, and even if you got a more with-it provider, it was still better to show up ultra-femme to your appointments. You'd get taken more seriously that way, the websites counseled.

So I did. But the doctor was surprised I showed up in a dress. “Did my staff treat you well when you came in?” she said. I told her they did, though today I have no memory if that's actually true. Maybe they didn't. My personal standards for what it meant to be treated well were lower back then.

“I can definitely answer some questions about hormones,” the doctor said. “I’ve worked with transsexuals for years, I’ve had hundreds of transsexual patients. I am one. Most people don’t know that.”

I didn’t.

She looked beautiful.

I thought, I'll never look like that.

“Do you smoke?”

I’d just bought a pack of cigarettes. “No.”

“That’s good, if you don’t smoke and you’re generally healthy, most people do pretty well, and then you’re just another dumb woman. I recommend you take a baby aspirin every day, helps prevent cancer. We don’t really know what hormone therapy can do. You can have health problems. There’s a higher risk of cancer, though most patients I’ve had who got cancer smoked—but we just don’t always know what can happen. If you don’t smoke and you take a baby aspirin every day, most people do pretty well. And then you’ll just be another dumb woman.”

Again: The higher risk of cancer thing hasn't born out to be true, and we do know what hormone therapy can do. But I guess she was mimicking the lines of the times, like the doctor in New York would a couple years later.

What sticks in my mind, though, is what she repeated over and over through the visit. Most people do pretty well. And then you're just another dumb woman. It kind of offended me at the time, like maybe I chalked it up to her having “internalized misogyny” or something. But now, when access to hormone therapy has turned into a sensationalized political battle, it's funny to turn that phrasing over. Like: Most people do do pretty well. I am just another dumb woman. I tried some drugs to fix a problem, discovered they were good for me, so I kept taking them. And, well, I'm not dead.