Most of my memories of being a “competitive” runner—a harrowing existence I chose in high school—are unpleasant. I remember swallowing saliva that stuck in my throat just as I needed to start surging at the end of a two-mile in outdoor track, forcing me to gag all around the first bend of the penultimate lap. I remember running the same race during indoor track with a cold, the dense, smoky air inside the building scorching my lungs. I ran into the frigid air outside after finishing, certain I was going to vomit. (I was fine after leaning against the wall for 10 minutes.) I remember trying to run 20 miles with my friend Jack just to see if we could—I crapped out at 17 and took so long to walk the rest of the way back to his house that he had to bike back out to find me after finishing the 20 on his own. I went to a birthday party after a meet and my thigh cramped while we knelt to take a group picture. I cried during the 10th mile of my second half-marathon and panicked when I crossed the finish line and the pain didn’t dissipate immediately. I ran over a bees’ nest with a teammate while warming up for a cross country meet; we realized what had happened as we felt sudden pinpricks in our legs, shouting “Bees!” and sprinting away in mortal fear. As I recounted the trauma to the team minutes later, another bee, which had slipped into my hoodie undetected, stung me in the side and I ripped off every top layer of clothing while yelling incoherently. I still had to run five kilometers.

I think running is the most joyless sport. I love to write about how mentally demanding tennis is, but at the end of the day hitting a neon-green ball with a racket at terrifying speeds is still fun. Running a distance event gives you no ball, no breaks, no variety, and few spectators. It’s all pain all the time. Swimmers may think they have the ultimate right to complain, since their sport shares all of running’s hellish features along with the fact that it's even harder to breathe. But come on, the fish who pursue that lifestyle are uniquely equipped to deal with it. Runners have it worst.

A few years after I stopped running consistently, I’m still trying to figure out my relationship with the sport. I can tell you that I miss racing about as much as the Trump presidency. The nerves beforehand were destructive and primarily about the incoming pain, not fear of underachieving. When things were bad late in a race—sore legs, each breath immediately followed by another and none of them bringing in any air, heart hammering in the chest and head, cramp in the side like a hot bowling ball under the skin, lungs aching from working overdrive—I’d back off my pace marginally because I was afraid of throwing up. If I stretched my mind to an unprecedentedly contorted position to imagine myself as a pro athlete, I’d be a prime target for broadcasters who like to say “he doesn’t seem to want it badly enough.” It’s no coincidence that I hoped to break five minutes in the mile and managed a personal best of 5:02.

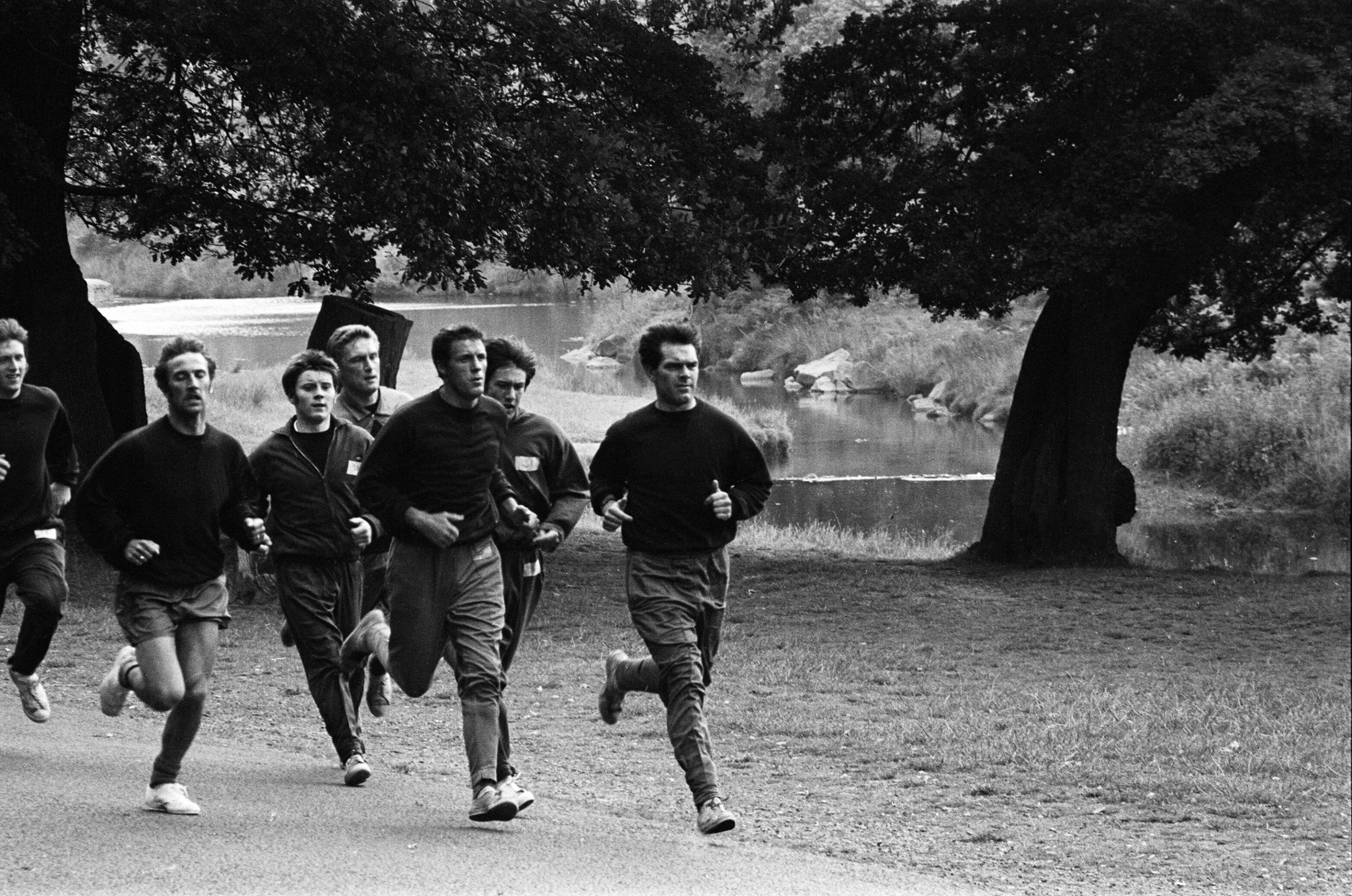

Where I found joy was the longer, slower runs. Exercise is somehow more fun when you have the breath to talk and, um, breathe. This is where you get runner’s high, which is not euphoria but lovely contentment brought on by finding a rhythm at the end of a run. The body’s distress signals stop spiking and the mind quiets for a few fleeting minutes. At this point in the run no one wants to stop before the agreed-upon mileage anymore, they’re all legitimately willing to keep grinding until the end. The soreness afterwards evokes pride, both a reminder of calories burned and permission to go get those calories right back. After finishing a long run with Jack and other teammates, we’d storm his kitchen and wolf down pretzels slathered in Nutella and whatever else had the misfortune of being around. It was unfailingly the best part of my week.

I’d feel accomplished after these runs. Even better, the usual flies that swarm my brain were gone. In John L. Parker, Jr.’s Again To Carthage (the sequel to Once A Runner, basically the Bible of running fiction), a coach writes a letter to the retired main character in which he floats a theory that distance runners and other endurance athletes sometimes use the endorphins from training to offset their mental health issues. The coach notes that he has no hard evidence, but this makes sense to me. Regardless of how I feel, running obliterates my thoughts for a few minutes and leaves in their place a song cycling endlessly that I time my strides to.

I didn’t stop running by choice, exactly. In 2020, I made the epic mistake of playing a club tennis match on an indoor hard court with a small hole in the bottom of my left shoe. I thought it would be fine! I junkballed and defended (read: scammed) my way to a win against a much better player, but the following day, the underside of my foot ached in a very particular spot beneath the first knuckle on my big toe. I was running 30 to 40 miles per week at the time and didn’t think much of the pain, so I continued with my eight and 10-mile runs on the weekends over streets and hills on pavement. The pain got worse. I stopped running, wore a boot for a while, used something called a bone stimulator, for which I’d smear gel on a circular sensor and slap that on the sore spot for half an hour a night, and started wearing thick flip-flops so I’d never have to walk without shoes. The issue has abated to the point that I can run a couple miles without pain—with personalized inserts in my shoes to lessen the pressure on the toe—but not like I used to.

When I try to run now, I’m playing catch-up for air within minutes. Jack joins me most of the time, when it doesn’t interfere with his workout schedule—he’s practically a bodybuilder now, no longer resembling the skinny kid I used to chase during high school races. Maybe it’s anxiety, or a one-note diet with too much bread and meat, or the lingering effects of COVID (though I've never tested positive). But it’s like I’m darting to a guarded well of air and can never completely fill up my bucket before I’m turned away. I am primarily a mouth-breather not just out of personal failing but perceived necessity. Sometimes I feel short of breath lying in bed—the same panic of running to exhaustion without the effort or the rewards. My 22-year-old body feels old.

I do miss the good parts. I liked hearing a doctor ask if I was an athlete because I had a low resting heart rate. I could eat the most disgustingly unhealthy food and feel like I had earned it. I felt strong. But I mostly miss the contentment during those runner’s highs. My ability to control my thoughts has diminished since I stopped running. Between that and my devastatingly narrow attention span, the only time I feel I have a solid handle on what passes through my head is in the first minute or so after waking up.

I took one more run yesterday to refamiliarize myself with the sensations, just a well-trodden mile to the edge of my neighborhood and back. I couldn’t manage more. No earbuds, just like when I used to train for races—you can't have earbuds when it matters. At first it was, dare I say, pleasant. 5 Seconds Of Summer’s “She Looks So Perfect” echoed in my brain. The initial pain was in my legs and I celebrated inwardly; this I could handle. But a slight slope I can’t even call a hill just after the halfway point reached into my soul and drained my defiance. My right side cramped after I crested the mountain—it’s worse than Everest, I’m sure of it. I put on a disgusting grimace so that passersby might take pity on me. The entire last half-mile got progressively worse until I felt I'd somehow break; people do not literally break in such situations, which is why they get better. Finally the driveway grew in my vision—you glorious concrete rectangle, you—and I labored in, lurched forward with my hands on my knees until the first beautiful full breath broke through.

I went inside. Midsection screaming, I poured and downed a cup of water. I stressed about the pain and nothing else.