A head of hair is a wild, unreliable thing. It never stays the same length. It never stays in the same place, unless you have Doctor Strange amounts of pomade on you. Look in the mirror right now and you’ll inevitably find not one, but many stray hairs poking out this way and that. It’s unavoidable but also quite natural for hair to behave this way.

It is also a massive problem if you happen to be making a film or a television show. When you shoot an actor in one location but have to digitally relocate them to another, which happens quite frequently, you have to bring along every last follicular imperfection with them. According to a compositor who worked on the first Avengers movie, this is not an easy task. Far from it.

“The heli-carrier sequence was shot on a runway in New Mexico. Scarlett Johansson had this curly red wig on. We had to figure out how to get sky behind her head instead of mountains. That was a huge pain in the ass.”

The compositor’s job is to merge all the elements from a movie, from the principal photography to the special and visual effects, into a single, final shot: the one you see in the theater or on your TV at home. For Johansson’s wig, the compositor and their team struggled to seamlessly blend the actress’s fake tresses into the finished background. They digitally cloned her wig. They feathered it. They blurred the edges to more easily integrate it. They even tried getting the original wig Johansson wore on set, so they could shoot the wig by itself on a green screen and then marry those shots with the original footage. In the end, they spent over two weeks working on that single head of hair, for an expository sequence in The Avengers that you almost certainly don’t remember.

“If I looked at the shot now,” that compositor said, “I could probably point out to you all of the morphs and dissolves that most people don’t see when watching it casually.”

That’s not the only time wigs have caused VFX artists headaches. Another source working on a period TV show said that they blew “80 percent” of their effects budgets fixing visible wig lines in the locked picture. This is the cost of filmmaking now. It’s not just in the battle scenes. In today’s Hollywood, compositors, along with all of their colleagues, are often left to clean up all of the messes left by writers, actors, directors, producers, and all of the other name-brand talent.

Those messes can be enormous—sometimes the crew on the set will outright forget to shoot something—and they can also be tiny, as tiny as a strand of hair. What matters most, though, is that those messes are forever growing, as more and more of what doesn’t go quite right on set is being left to a post-production workforce that is disparate, overworked, confused, and exploited.

In the process of reporting this story, Defector talked to a dozen people who all work in various aspects of post-production: compositors, supervisors, technicians, generalists, VFX coordinators, colorists, editors, and more. All were granted anonymity due to signing nondisclosure agreements, as well as fear of retaliation within the industry. And all described experiencing similar problems with their work, across projects of various budgets and sizes, including The Walking Dead, Moon Knight, a terrible sequel to 300, and Guillermo del Toro’s upcoming Netflix series, Cabinet of Curiosities.

These workers are part of a beloved art form undergoing a rebirth, on the fly, across a global patchwork of studios, effects houses, boutique shops, and freelance contractors. Visual effects departments didn’t even exist, particularly in television, until roughly a decade ago. Now they, along with secondary effects houses, are being tasked with a sizable portion, if not a majority, of post-production duties on shows that have hard premiere dates which rarely, if ever, get moved. One source told Defector that studios almost never take post-production staffing into account when they set a release date. “It's so low on the pole that it’s not a consideration.”

Once the time comes to do that post-production work, the crunching begins. These are workers who, similar to video game developers, will work more than 14-hour days for days on end, on long-gestating projects and on emergency, two-day turnaround jobs. Many of them work freelance. Others work for mammoth VFX houses like MPC, which in July announced that it was freezing pay raises for all employees, according to the Animation and Visual Effects Union. (MPC did not respond to a request for comment.) Some work in Los Angeles, others work in effects hubs like Vancouver, and still others move to whichever city has enough tax incentives for Hollywood to plant its flag and make it the next effects hub. There’s a cycle to this, as laid out by one compositor:

“When you say ‘Hollywood,’ you're talking about a culture that had over a century to build itself in one place, and that's not really happening with effects right now. Artists move to the next place, then to the next place, then to the next place.”

But no matter where they ply their trade, and despite the technology they have on hand, these artists can’t always fix everything they touch. And what they cannot fix becomes a problem for the consumer, who ends up getting lower-quality visual effects for their dollar. Audiences have been exposed to enough shoddy digital effects this century that the term “CGI” itself now implies poor craftsmanship. This problem is so widespread in Hollywood, not to mention accepted, that producers have their own acronym for effects work that passes muster for them but might not for audiences: a final approval note of CBB, for Could Be Better. And producers aren’t the only ones to both acknowledge the problem and let it slide. Oscar-winning writer/director Taika Waititi recently felt free to mock the visual effects in his own movie, Thor: Love and Thunder.

That Waititi would so playfully deride work done by his people, in a film he directed, shows how strangely disconnected he is to those people and, by extension, to the work they do that eventually bears his possessory credit. That disconnect is rampant. Not just at Marvel, but everywhere. One coordinator I spoke with said the show he was working on was using 15 different effects houses at the same time. One former VFX producer told us that his house would routinely outsource their own assignments to other shops without telling the client they were doing so, a practice that they say is common within the industry. It’s just not that you can’t see how your effects have been sourced, but that many of the people in charge of the movie you’re watching can’t see it either, until it’s already been released and they feel free to mock it.

As one post-production manager told Defector, “I think that this is a pinch point economically for studios where you can achieve savings by, honestly, mistreating employees.”

Every project in Hollywood begins with an idea. Whether the idea is original, recycled, or stolen is beside the point. What matters is that this is the freest part of the endeavor: the moment where anything can be anything, because what creative person ever wants to limit their own imagination? After all, George R.R. Martin, a former TV writer, deliberately wrote his A Song of Ice and Fire novels to be unfilmable. What Martin couldn’t have known back when he started was that visual-effects technology would soon catch up to his vision, allowing his epic to be fully realized, not to mention completed, by its namesake HBO series (although that series itself had a couple of highly memorable visual fuckups). So if HBO was able to make Game of Thrones, who doesn’t want to believe that Hollywood magic can make any idea, big or small, live in full on a screen?

It can be done, but then the question becomes who will be creating those impossible visuals, and how much time and money they’ll have to do it. In Hollywood, the people who make this magic happen are broken down into two camps: visual effects and special effects. Special effects, also known as practical effects, cover effects done in camera, like models, stunts, and riggings. Visual effects cover all of the digitally generated effects that are inserted into the project after shooting is complete. For the majority of the film industry’s existence, practical effects were the dominant form, spanning from the stop-motion monsters of 1933’s King Kong all the way to George Lucas creating miniatures for Star Wars in 1977 that, when put on celluloid and projected on the big screen, turned into breathtaking Star Destroyers.

There was one old Harrison Ford project where they made him up, but we had to remove his double chin. He was old and flabby, and so we gave him a facelift. It was no big deal. It was just funny.

However, at the turn of this century, when Lucas relied almost entirely on green screens to film his Star Wars prequels—using non-sets that limited his actors’ ability to get into character—VFX emerged as the preferred way to make the unfilmable filmable. Studios today don’t have to manipulate clay figurines or build miniatures if they don’t want to. Or, more accurately, if they don’t want to pay for it. And why would they? Why risk saddling Steven Spielberg with a broken mechanical shark for Jaws, forcing him to engineer creative story solutions to an on-set crisis, when they could simply farm the creation of that shark out to post-production instead? Those guys can make anything, can’t they? After all, as one source told me, “There's really nothing else in the VFX world that hasn't been done yet.”

Producers and studios are using the fact that VFX can do anything to make those departments do everything. As another visual-effects worker told Defector, “People keep writing things into scripts that they could never do practically.” When this happens, not much thought is given to how those visuals will be created. Another source summed up the approach bluntly: “People are not giving a lot of thought to, Is this film filmable? They're like, Someone else will figure that out. That's not my problem.”

This means that it becomes a visual-effects team’s problem. Movie studios and the Hollywood press might have you under the impression that a film with a large budget and crew—crews that can number into the thousands—means you’re going to get bigger and better spectacles than you would see otherwise. But the truth is that a $200 million film is subject to the same amount of bureaucracy and waste as any other product made by any other massive conglomerate. And, as with those other conglomerates, it’s the low-end workers who suffer the most.

With the exception of a few legacy directors—Spielberg, Quentin Tarantino, etc.—no director shoots on physical film stock anymore. All principal photography has shifted over to digital, which is both less delicate than the analog stuff and has far more capacity. As a result, a director never needs to say “cut” on set if they don’t want to. They can keep the camera rolling indefinitely to capture inspiration any time it strikes, or any time an actor blithely tosses off an ad lib that’s better than what’s in the script. This is the most romantic part of film and television production, but it also results in a mountain of footage for everyone in post to work through. Before a project even reaches a visual-effects worker's hands, they’re already prepared to deal with far more raw material than filmmakers of the past ever did. From an editor on The Walking Dead:

“You rarely get less than three and a half hours of footage in a day. There were definitely episodes of Walking Dead where I got up to seven. It's extra time on the colorist, the loader, and everyone else involved.”

Don’t you get notes from the director saying which takes they liked on set?

“You'd think, wouldn't you? People forget that there's an editor. A really good script supervisor (whose job is to ensure script continuity from shot to shot) will get that information, even if the director is not forthcoming.”

But you don't always get a great script supervisor.

“You don't.”

What gets shot—often across multiple units where the director, or even the director of photography, might not be present at all—gets fed into a disk. If you’ve ever tried to email a 60-second video of your kid to a friend, you know that video files can chew up a considerable amount of space and bandwidth. Now imagine how much space a film, and every single element used in the production of that film, takes up. You still won’t be imagining enough. Someone has to manage that disk and all of its data, weeding out discarded shots and making sure everyone is working on the same version of the same thing. This person is called a technician. One of those technicians told Defector that they were working on a Marvel show where the disk occupied nearly a petabyte, or a thousand terabytes, of space. When Marvel ordered locked shots to be redone or to be re-imagined entirely, a practice that sources told Defector the studio is notorious for, that technician had to physically remove the original shots off the disk. That discarded footage was no small expense for Marvel to produce.

“They left so much money on the floor. They might have had a $30 million budget for visual effects and pissed away $5 million of it.”

(Marvel did not respond to a request for comment.)

In post, wasted money comes in multiple forms. It can come in the form of the aforementioned revisions. It can come in the form of changing frame rates on an entire TV show from 24 frames per second to 60 because a network is, rationally or not, dedicated to that second number. It can come in the form of simply waiting. Effects artists start off working with rough footage before converting it to the full resolution you end up watching on screen. That conversion is called rendering: another job that gets outsourced by effects houses on occasion, often to websites called render farms. While workers back at the house stand by as it renders fully, they either wait on the clock, or they switch over to one of the many other shows they've been assigned.

“There's a lot of hurry up and wait,” a supervisor told Defector. “It makes me jaded as hell. All I want to do is my job, then I become disillusioned and scroll through Twitter instead of making stuff better.”

More waste comes in the form of future-proofing, where effects teams have to increase the picture resolution even further and then archive it for a hypothetical next generation of television sets. The higher the resolution, the more visible imperfections become, often by orders of magnitude. All of those new imperfections have to be corrected. In the case of Seinfeld, which was originally shot on film and recently scanned and digitally remastered to 4K, future-proofing ended up being a shrewd, and ultimately lucrative, endeavor. But for other series, which are likely not one of the most popular network comedies in history, and are not being future-proofed decades after their run is over, those higher-resolution versions never end up being necessary.

Waste also comes in the form of fixing the visual deficiencies of a sequence shot on a monochromatic background. You know this as green-screening, but really any non-white color can be used. Those background colors are sometimes chosen by the director of photography at random, and can end up having disastrous post-production consequences.

“I can't fully articulate why any DP, or whoever's making that decision, chooses one backdrop color over the other," one compositor told me. "I just know every time we get them, we complain. Who shot this? Why did they shoot it this way?”

Ideally, there would be at least one head visual effects supervisor on set at all times. That supervisor can come in one of two flavors: one from the studio, with their eye constantly on the budget, the other from the effects house to anticipate post-production needs and how their house will handle them. Knowing who to take orders from after the fact is difficult enough for VFX artists. But oftentimes, as one source told Defector, there’s no supervisor on set from either side.

“If they're not there, then what you get in the actual footage could be a lot more difficult to work with.”

Exactly how much money do studios save by not having their own set supervisor there?

“A laughable amount. Maybe $1,500 a day.”

Three sources told Defector that they also rarely deal directly with the director or a director of photography to ensure picture consistency, an observation echoed by an anonymous source who spoke last week to New York magazine. Some directors, one of our sources noted, don't understand visual effects enough to offer useful feedback anyway. “They just defer to the visual supervisor,” they told us. Otherwise, all VFX artists get are orders from “the client,” and those orders are often conflicting, late, or both. From a former VFX producer:

“There are so many differing views and egos involved that it wasn’t uncommon to be on the hundredth version of a CGI animal or big action shot. Either might be on screen for only a split second. The amount of notes and revisions would inevitably push our delivery dates, which would always be an annoying conversation with the client. They usually wouldn’t understand the time that even rendering, let alone creative, takes.”

When effects artists aren’t having their time wasted, they’re often tasked with making beauty fixes. Some actors have digital fixes to their hair, among many of their other physical features, written into their contracts. Other actors, quite literally, won’t look the part.

“We fixed faces all the time," one technician said. "There was one old Harrison Ford project where they made him up, but we had to remove his double chin. He was old and flabby, and so we gave him a facelift. It was no big deal. It was just funny.”

(Representatives for Harrison Ford did not respond to a request for comment.)

Funny, but also illustrative of the ways in which post-production crews exhaust hours and money fixing things that either couldn’t be done on set, or were done haphazardly. These flubs aren’t necessarily the fault of the cast and crew. There are only so many hours they can film in a day, only so many circumstances on that set that they can control, and only so many ways they can tell Harrison Ford that he might be out of shape. If you’ve ever been on a film set, you also know that exhaustion is baked into the day. Without an exacting (not to mention powerful) director like David Fincher in charge, there’s very little time and motivation to wrap the day having accounted for every last possible speck of coverage. But sometimes, there is outright neglect, and it isn’t always hard to tell which projects might have suffered from it.

They left so much money on the floor. They might have had a $30 million budget for visual effects and pissed away $5 million of it.

“I worked on Click,” said one post-production manager. “That was what you would expect from an Adam Sandler movie, which is: They didn't necessarily shoot it as well as they could have, but they just winged it and hoped for the best.”

Then there are the notes, which are where both waste and needless busywork rudely join forces. At least two of the artists Defector talked to spoke highly of Marvel, largely because they said that Marvel pays effects houses promptly, honors overage fees, and, on certain projects, has a streamlined pre-production process where everything is clear to everyone. Many others, like our technician, were less generous in their assessment.

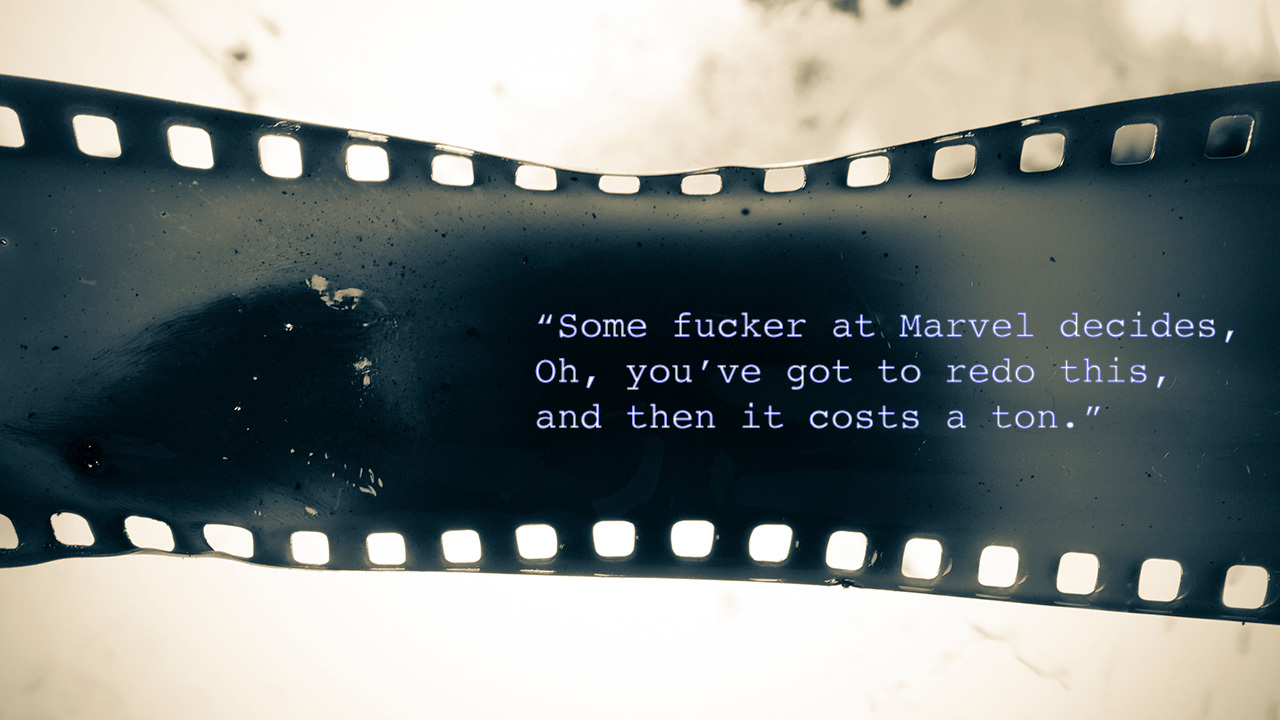

“Some fucker at Marvel decides, Oh, you’ve got to redo this, and then it costs a ton.”

There was a time, that technician told Defector, when Marvel entrusted effects houses to work out the visuals on shots that the studio couldn’t quite wrap their heads around. Those rare moments allowed Marvel’s VFX artists to be artists: creative, free, and resourceful.

“I think that’s some of our best work,” they said. “That never happens anymore.”

Instead, they get notes. Often very late ones, which leave post-production units with less time, not to mention less money, to execute large sequences that are supposed to befit the Marvel brand name. You, the audience, are often on the receiving end of those rush jobs. The lighting will be inconsistent, often within a single shot. The laws of physics go ignored. Images look “floaty.” The color palette of the film becomes a mess.

“The volume is just exploding,” a source told Defector. “And the ideas are just terrible. That was a beautifully rendered hippo from what I saw in Moon Knight, but whose idea was that? It wasn't a visual effects studio idea. And when you see something like Morbius, you already know it's a piece of shit. So of course the effects are going to look like shit! You get those really janky scenes where the star's standing in the middle of a big room and they're staring up at the wonder around them. The camera slowly pivots around them. People are going to get tired of that scene.”

Perhaps the apex of this creative fatigue was Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, which underwent extensive reshoots but didn’t have enough of an effects budget to cover that new footage adequately. As a result, the effects in the opening sequence of the film are about as convincing as a Windows 98 screensaver. One supervisor expressed to Defector their exasperation not only with the process on that film, but with the startlingly inert creative choices that went into it.

“When you see something like the first third of Doctor Strange, you're like, Why not do something more interesting, where you're not straining your budget and 1,000 artists to try and make something that you know is going to look substandard? Why not try something else when you have a good director like Sam Raimi?"

(Sam Raimi’s publicist did not respond to a request for comment.)

Marvel allowed the back half of Multiverse of Madness to showcase far more of Raimi’s hallmark directing style, but by then it was too late for the entire film to play out as a cohesive whole. It still grossed nearly a billion dollars worldwide.

Then there is Netflix, which one show coordinator told Defector was, by far, the “worst” company any effects person could work for. On a Vanessa Hudgens Christmas movie called The Knight Before Christmas, at the behest of director Monika Mitchell, who was irrationally hellbent on perfecting it, the coordinator’s effects team had to redo a single shot of a castle dozens of times after they had completed 90 percent of the film. (Mitchell did not respond to a request for comment.)

For a figure skating show called Spinning Out, Netflix expanded its demands on the effects house until that house had no choice but to farm out some of their work to India. But regardless of whether or not Netflix’s effects are outsourced, the end product can still turn out poorly, not because of who’s making those effects, but who’s ordering them. The case study of Guillermo del Toro's Cabinet of Curiosities can explain why. A coordinator on that show told Defector that they and their crew had nearly finished the second episode of that series while del Toro was out doing publicity for the release of Nightmare Alley. When del Toro turned his attention to Cabinet, he wanted to put his “fingerprint” on that episode, leaving the VFX team to re-work its visuals months after they had been finished, and with barely any time to spare. Because of del Toro’s curveballs, the coordinator and their team were still, as of our interview in June, working on effects that should have been finished back in February.

“And he’d approved a visual effects supervisor on his side to work with! Now he was superseding them, and now we have to deal with it on our side. The work suffers.”

(Representatives for del Toro and Netflix did not respond to a request for comment.)

Across effects houses and among freelance artists, there is a mix of confusion and burnout. Just as sets can be exhausting, so too can sitting in front of a bank of monitors for 14 hours a day poring over footage. One source who spoke to Defector left the industry over a year ago due to stress. Another said that they often get “lost in the sauce,” staring at frames over and over again until they barely know what they’re looking at. Many of these artists can’t turn down work, in part because they need to eat, but also because they can’t afford to make a client unhappy, no matter how unreasonable that client may be. From a source who recently fled the occupation:

“Really it becomes, how friendly are you with the client? Do you want to keep their work? Do you want to get more work from them? If so, you may say, ‘Let's not charge the overage on this one.’ You don't want to go back out to Marvel or someone else and say, ‘Hey, you changed your mind, so this is going to cost you $100,000 extra.’ We might try to fold that in to make Marvel happy so that they give us another 100 shots in a month.”

Marvel is hardly alone in putting pressure, both consciously and unconsciously, on houses and artists. Future jobs with every client always feel as if they are at stake, particularly if the client is a streaming service (Netflix, etc.) that’s under enormous pressure to keep up with their competition. The pressure any client feels gets passed on, like everything else, to the below-the-line crew. One Flame artist described the problem to Defector like this:

“It's like if you hired somebody to come over and redo your bathroom, and then they got here and you said, Well, actually I want to add a second story, but can you do that for the same budget? A contractor would tell you no. But in our world, you can't quite say no.”

When the houses don’t say no, the incoming workload can often get assigned to junior-level artists who don’t have enough formal training. Or the house assigned is a boutique studio—one with less output capacity, or one that might not specialize in the type of effects needed, i.e. creature and underwater effects—chipping in on work that a bigger house lacked the capacity to handle. As a result, these artists are often asked to do work that they know they won’t end up being proud of. This is the point where artistry becomes busywork: just another thing people need to get off their desk. One source who spoke to Defector knows that work can end up looking rough on screen, but often it’s the best they can do given the footage, time, and resources at hand.

“This last TV show I was on, there was a shot and this guy was lit from behind so hard," they said. "He just had this giant rim going all around his body. We had to go in and paint out that harsh rim and tamp it down. It turns into mush. I don't even want to put that shot out, but that's what the client wants. So it's like, All right. I hope my watermark or my name isn't on it, because people are going to wonder the fuck happened."

In 2019, the United States spent over $65 billion in TV and film production: a number consistent going back through at least the decade prior. But despite the size of the U.S. filmmaking industry, the effects world within it isn’t unionized. When Ang Lee’s Life of Pi was up for a Best Visual Effects statue at the 2013 Oscars, the ceremony was protested outside by workers on that film who had just sued their effects house, Rhythm & Hues, for firing 250 of them without the 60-day advance notice mandated by California law. R&H had filed for bankruptcy weeks prior to the show. Life of Pi won the effects Oscar anyway. When effects supervisor Bill Westenhofer took the stage and attempted to thank R&H artists, acknowledging that the company was in “severe financial difficulties right now,” the house orchestra upped their volume while playing him off the stage with the Jaws theme. R&H founder John Hughes—no, not that one—would go on to found another VFX firm four years later.

“The industry needs to unionize, full stop," one VFX producer said. "VFX-driven movies overwhelmingly rule the box office, and as an industry we simply don't see the returns that we should. Other below-the-line unions take residuals from shows and use them to benefit the union: healthcare, pension plans, continuing education. We in VFX get none of that.”

Instead, VFX artists remain at the mercy of their employers, and they aren’t allowed to showcase their work because studios safeguard final cuts of their movies and shows with uncommon zeal. As a VFX worker, you have to have a showreel of your work on hand to show other potential employers, or to new clients at your current place of employment. But those reels are much more difficult for the artists to compile than you might suspect. These are not people who are allowed to use complicated sample reels, known as breakaparts, that are commissioned by studios to show off how their effects are done, nor can they afford to make a breakapart of their own to show off. (One artist told Defector that they attempted the latter one time and then swore they’d never do it again.) Breakaparts are extremely expensive and time-consuming to produce, and studios don’t want unauthorized production secrets potentially leaking out to the general public. Control of their content is paramount for spoiler prevention, for licensing, and for future asset re-use.

The industry needs to unionize, full stop.

And the term “asset” doesn’t mean the idea behind a show itself. Effects get recycled the same way franchise characters do, and perhaps more often. One writer/director advises you to notice the sky the next time you watch a sci-fi show or film, because, “that is most likely pulled from some other asset that they're compositing and building from.” And when Marvel filmed its Moon Knight series for Disney Plus, one show coordinator told Defector that star Oscar Isaac was “nowhere near” any of the on-set footage of the title character that they worked on. Instead, they worked with a digitally costumed Moon Knight asset that had been passed onto them by another effects house. That won’t be the last time that asset is used. Disney will own that asset forever. No VFX artist ever will.

(Disney did not respond to a request for comment on this story.)

With these assets so precious, younger artists are often lucky if they get a Quicktime of their work to show prospective employers. One artist told Defector that many of them are forced to pirate their own work off the internet, just so that they have something to show off alongside their résumé. And who knows if they’ll even have time to do that, because more work is always forthcoming. The threat of an IATSE strike last fall made studios a bit more hesitant to overload their vendors. But when a deal was struck, that hesitancy abated. A show coordinator told Defector that there is now little in the way of relief on the horizon.

“The whole industry seems a bit depressed on the heels of Marvel’s Phase Five and Six announcement, specifically just because of the insane amount of work it’ll be on its own,” they said. “They’re not the appealing client they used to be. A lot of burnout is setting in.”

Not that studios, nor their above-the-line talent, will be grateful for the work they get back. You saw Taika Waititi savaging his effects team in the clip at the beginning of this story, but at least Waititi was generous enough to acknowledge the effects at all. One technician fondly recalled all of the effects work they did on James Mangold’s Ford v Ferrari, a film that married practical effects and visual effects together with great dexterity. Then came the press tour, in which Matt Damon told noted car aficionado Jay Leno that, when it came to the film’s driving sequences, “Nothing was CGI. All of that was in-camera.” The technician and their colleagues noticed the slight, passing around the video of Damon and Leno to one another with equal parts amusement and irritation.

“We, in fact, had just poured tons of CG into that shot. They worked their asses off on set, doing as much practical stuff as they could. But there was always stuff to be sweetened. It was like, You lying sack of shit. You don't know what you're talking about.”

(When Defector reached out to Damon’s publicity team for comment, they said the actor was currently out of the country filming and suggested we contact Mangold’s reps instead. As of right now, we have heard nothing else back from either camp.)

That same technician was invited to a special screening of Black Panther for visual effects artists. But when the Marvel rep, a white person, came out to introduce the film, “They were just so full of themselves. They were billing this as like the film equivalent of reparations. The disconnect was unbelievable. We were there to see our cohorts. But, as far as Marvel was concerned, they were on the leading edge of the civil rights movement. I just found it very discordant.”

A different sort of discordance inevitably ends up plaguing the end product. In 2019, venerable director Martin Scorsese wrote an op-ed in The New York Times excoriating the film industry, Marvel in particular, for abandoning the craft of filmmaking entirely in favor of making what he called “perfect products manufactured for immediate consumption.” But now that you’ve heard from the artists and supervisors, you know that these are not, by any means, perfect products. Many of the people Defector spoke to for this story were proud of the work they’d done, on projects that included Bong Joon-ho’s Okja, The Walking Dead, and made-for-TV movies that air on The Hallmark Channel. Other times, they know the work Could Be Better. One project manager had to remaster all of Malcolm in the Middle, only to notice “ghosting”—where the image of an actor trails behind them for a split second—in the final product. Another artist worked on 2014’s 300: Rise of an Empire, which ended up looking very much the way you would expect 300: Rise of an Empire to look.

“It was shot in Bulgaria or Romania. One of the two. [Note: It was Bulgaria.] These characters are on a green screen soundstage and they're all on boats. But the boats don't move. There's no ocean motion at all. We're adding some really fake 2D rocking motion to every single shot, with everyone standing perfectly still on these boats. As if the ocean wasn't moving. That stuff is a giveaway. You know it was on a soundstage somewhere.”

There is some hope among below-the-line workers in Hollywood. Many of them were allowed to work remotely full time in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, and many studios and houses have been content to keep that setup ongoing. Also, this digitized phase of moviemaking may soon evolve into 100-percent virtual production, with green screens and blue screens permanently replaced by virtual sets: the kind used by Disney to produce The Mandalorian.

While The Mandalorian, like Ford v Ferrari, had more than its fair share of sweetening done in post, the virtual sets their production crew constructed using Unreal Engine—a technology first developed for gaming that has quickly been adopted by the film industry—not only helped the actors on set get into character, they also served as an advanced form of pre-visualization for workers on the back end, especially in terms of lighting. The result was an unqualified success, both creatively and financially, and the show serves as a potential signpost for where postproduction is soon to be headed.

Producers and other C-suite denizens of Hollywood might be slow to embrace virtual production, but here is a place where effects houses can lead them, instead of the other way around. While one supervisor noted that close-ups on a virtual set can be tricky, nearly everyone Defector spoke to about Unreal Engine and other virtual production tools is relatively bullish on their potential to make visuals cleaner while also making their lives easier. A supervisor told Defector that they guessed that 70 percent of virtual production shots on The Mandalorian still required touching up, but that extra busywork could soon be drastically reduced.

“I think The Mandalorian sort of tricked the industry and said, Hey, look how possible this is, and then everybody started throwing money at it. But I think in the next few years that percentage is going to be much lower. This was ultimately the first proof of concept that this could be done in a series format.”

Of course, not every TV show in the future will serve as the launching point for a billion-dollar streaming service, using one of the most beloved sci-fi franchises of all time as its story base. But many people in post-production still see a future where virtual production allows them to meet expectations and to still tell human stories, without the job costing them their lives or their sanity.

For now, artists have adopted a strange mix of both healthy perspective and weary resignation. Many of our sources, as audience members, are unbothered by shoddy effects work, so long as the story itself is “awesome,” as one source put it. Others are more than happy to have low expectations, particularly when it comes to television shows, where bad effects were once both expected and accepted. The proliferation of bad effects can even bring a perverse sense of relief to these workers, because you can’t begin the process of fixing a problem this pervasive and systemic until it’s been properly identified. It’s good if you see the flaws, if you understand that someone was there.