I was talking to a friend about how many people had played in the Major Leagues shortly before my plastic Adirondack chair imploded. Exactly how shortly I don't recall, but we might as well imagine it happening when it would have been funniest, which is immediately after. We had all been in the lake by then, and all of our chairs had been sitting out on the concrete dock for many years, growing brittle through winters and rain and the pressure of generations of terrible brown spiders and, as often as our friends will allow, my own damp and hideous bulk. My chair had groaned a bit before giving out utterly, both its backmost legs shearing off and much of the rest of the chair pebbling against the dock on impact, but also this chair and its dusty twins had been groaning for years. We knew each other; I might have said, before this, that we were friendly.

But if this moment was always coming, it would make the best comic sense if it happened right after my friend told me that there had been something like 20,000 big league players in history. This is a lot to think about, and certainly enough to obliterate a dried-out old dock chair even before my own awful ass enters the equation. So let's think about it as that: two dudes talking about the enormity of baseball history, in the context of the online baseball history game Immaculate Grid, and getting after it so intensely that the combined weight—of my middle-aged corpus, and all those baseball lives—was just too much for that old chair, built as it was for normal use by normal people under normal conditions. I went out like an uptight authority figure in an '80s television commercial for some chewy candy, all "whoa whoa whoa" and hapless.

Visually, maybe you would like to imagine the beefy, bespectacled former Phillies slugger Greg Luzinski putting me through a weary bit of plastic outdoor furniture as he might at a Buffalo Bills tailgate. Or maybe it's Scott Rolen. The thing is that it has to be someone on the Phillies who drove in 100 runs in a season. The specifics matter, but also the game piles up on you. It gets heavy. It splashes your ass on the concrete and you get up chuckling. You get up thinking that there's also Dick Allen, obviously, too many people forget about him. Darren Daulton did it twice. Anyway, you just have to pick one.

The Early Squares

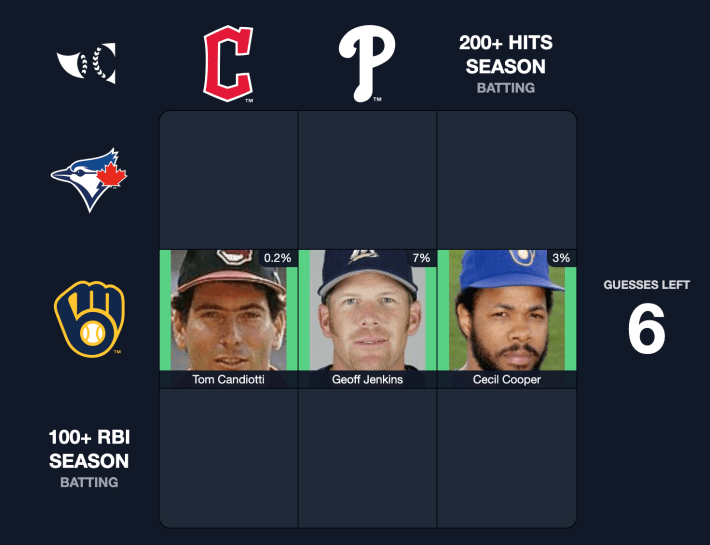

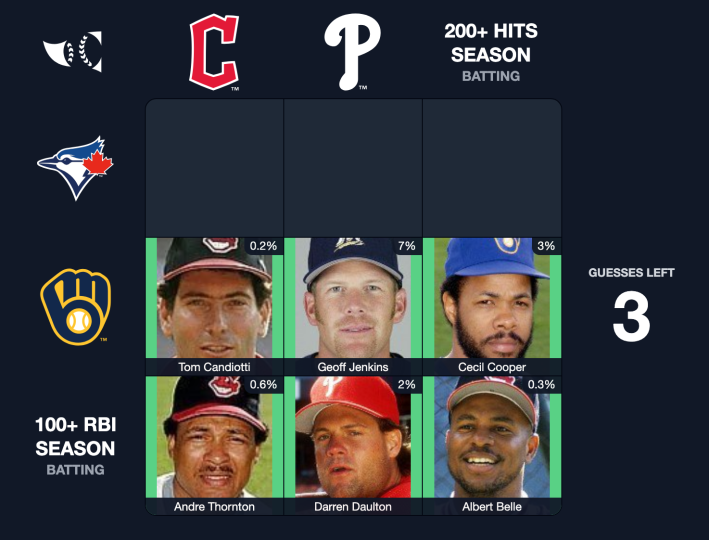

The game itself, which was developed by a programmer in Georgia and purchased by Sports Reference earlier this month, is very simple. You get nine squares in three rows of three, and three prompts; generally this is two teams and an individual achievement, like a 100 RBI season or a Gold Glove, on each axis. The game is about the way baseball careers overlap, because the challenge is to pick a player who fits the necessary criteria for each square. It helps to look at it:

The idea of this post was to provide some insight into my process in filling these things out. It's a good idea, but sadly I do not really have a process that I'm aware of. The little screensaver carousel of worthless baseball cards from my youth that scrolls infinitely in my mind during all the hours that I am awake simply picks up speed, and I grab at possible options like someone in one of those prize phonebooths where dollar bills are being blown around and the aim is to grab as many as possible. My approach to this is not necessarily any more reasoned, and necessarily not any more dignified, than that. I do not really have processes, as a general rule, or anyway I don't really have them to the extent that they are distinguishable from simple habits or just "my neuroses." This is why I am such a pleasant and normal person to work with.

But I guess I do have some method to it. In the early squares, which are the ones that for some reason or other come to mind more easily, I just pick up what I see lying around and put it where it seems like it might belong. This is why the most common answers in the game, among the hundreds of thousands of people that play it on any given day, tend to be current big leaguers. It's the nature of the game that everyone is in the same stupid phonebooth, with the same dollar bills whipping around. But, here and only here, if you have spent enough time crowding out all the interesting or important things you ever learned in your life with faint but sticky memories of the 1986 Topps baseball set, you will have an advantage. Or anyway more and more worn-out bills to grab.

So: I probably saw Tom Candiotti throw his knuckleball at some point, but it wasn't when he was with the Brewers; I certainly never saw Cecil Cooper play, although I remember pulling his card from packs and asking my father if he was good; I remember Geoff Jenkins because he is one of my favorite types of baseball player, The Rectangular Homer Guy. All three were in the Brewers part of my brain, which unfortunately is located where the "basic facts about global history" part of my brain used to be. Not what you want, but nevertheless a good start.

The Middle Bit

It would probably be smart to stick with the team-centric approach, but I have already established that I am not really into that sort of thing. As statistical categories go, 100 RBI is something of a fat pitch. I do not really know who has ever won a Silver Slugger, and even big bold-type achievements like 300 Career Wins or 500 Career Homers present some blind spots for me, and so I tend to save that type of column for last. This strategy of hoping that difficult things might go away on their own is one that I picked up as a very young child. I can't really recommend it, although I still rely on it.

But 100 RBI isn't really one of those, because not so long ago even many lousy teams would have someone in their lineup drive in 100 runs. In a situation like this, I trust my instincts, which is to say that 1) I remember which guys won "Diamond King" status from Donruss in their sprawling sets from the '80s and '90s and 2) I know that basically anyone who played baseball before the year 2000 will deliver a low rarity score, which for some reason is a thing that I want.

Andre Thornton, who I have only ever known as his own bespectacled Donruss Diamond King illustration and later as the subject of a lovely essay in Steven Goldman's book Baseball's Brief Lives, did it twice. In 1982, when Thornton's 116 RBI were apparently third in the American League, he was one of 18 big leaguers to top the century mark. I didn't actually know any of this, of course, then or now. I was a four-year-old with a bowl cut when it happened, and I didn't know what baseball was; I slept with Matchbox cars clenched in my fists and woke up talking full nonsense in an absurd high-pitched voice. Even as I entered his name, it was because it just seemed like a reasonable guess.

Not a lot of the people that fill these grids out were any more cognizant of even Darren Daulton's career than I was of Andre Thornton's, and for something like the same reason. It is a weird but understandable quirk of the grid that no one seems to remember Albert Belle, who is both one of the best hitters not in the Hall of Fame despite his brief peak and a true creep. This is where being an old doofus whose brain don't really "work" starts to pay some real dividends.

The Home Stretch

You will learn some things about yourself while filling out the Immaculate Grid. This goes beyond the inevitable and sobering realization of how many of Jeff Conine's teams you recall (all except for the Phillies, where he spent part of a season near the end of his career) relative to how much of even the broad strokes of Karl Marx's "Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte," which in this example you/me read while in college, you/me can recall today (absolutely none). I have learned, in filling out these dumb grids two or sometimes three times per day in different incognito-mode browser windows, that I remember players by type—the aforementioned rectangular wind machine sluggers and the various sketchy mustachioed starting pitchers of the George H.W. Bush years and the damp, grumpy-looking relievers of the '00s. I remember some teams very well and others hardly at all, and this has nothing to do with whether I have ever cared about those teams or not. I honestly don't know what it has to do with, or why I remember the Royals so much more than I do the Rockies. I have also discovered that, during the years when I was in college and immediately after, when I was happily adrift and half in the bag in a world of nascent and spotty internet, with both new pursuits and the new freedom to pursue them, I was not really processing much baseball information.

These are not important blind spots, really, and I doubt I'd know about them at all if I weren't going looking for them a few times per day, in this particular way. But I can tell you now, with some confidence, that the Blue Jays are one of those. I remember their cool teams of the 1980s, which never won anything despite having some guys whose baseball cards I valued very highly, and I mostly remember the World Series teams of the next decade. And then there's a fuzzy image of Tom Henke's face for a couple decades, and then suddenly Bo Bichette is getting picked off second base in the present day.

This is why I saved them for last. Because I am missing two decades of information that, while not useful in any context but this one, would be highly useful here. So I stick to the parts of the street that are illuminated. Everything else is either a shadow or an open manhole.

Here, again, my typological preferences revealed themselves in ways that I found startling, if not really surprising.

I do tend to remember 1980s players who photographed strangely, and Pat Tabler, a pinch-hitting ace touted as one of the most clutch players of his era, is memorable in that regard for his robust blond perm and wispy matching mustache. The clutch stuff is questionable, in retrospect; the Ohio Lothario Circa 1987 aesthetics are undeniable. Darrin Fletcher is probably the only one of these guys that I remember as anything but a baseball card; I'm sure I saw him play against the Mets when he was with the Expos or Phillies. Given where all those teams were, then, that game was surely meaningless in every meaningful sense, but it was enough for me to notice, some time later, when I pulled his card from a pack and saw that he was with the Blue Jays. There are grandparents whose faces I can only barely recall, but I vividly remember this.

The hardest square to fill was, per my proprietary method, the one I saved for last. I thought of Tony Fernandez as one of the coolest players of my youth, because he had a cool nickname—"El Cabeza" just means The Head—and played an alternately smooth and vicious shortstop while hitting much better than shortstops generally did back then. Again, I am going by the fact that I had his baseball cards, and read about him in The Sporting News, and sometimes saw him on the syndicated highlight show This Week In Baseball. I couldn't have really watched Fernandez if I wanted to, because he did all that in Toronto—and Cleveland, and with both New York teams, and probably with some others that I can't remember—and because I did not live in Toronto.

I was just somehow absorbing all that information, in the way that people absorbed information before our relationship to information became that of a foie gras goose and the butter being forced through its feeding tube. Crucially, and in lieu of anything that might have been useful to me in the long pre-Immaculate Grid portion of my life, I retained that impression of Tony Fernandez. He died in 2020 and I retain it still. Cabeza. Pretty cool, pretty good, definitely a decent bet to have had 200 hits in a season with the Blue Jays.

Which it turns out Fernandez did, exactly once. I got lucky on this, I guess, but the same could be said of anyone who got it right. I could think of two other, better-known players who surely got 200 hits with the Jays in Paul Molitor and John Olerud, and a few others who might have done it (George Bell and Alexis Rios and sweet goofy Bo Bichette) but turned out to have fallen just short. To be fair to them, that's a lot of hits—Bichette has led the American League in hits for three straight seasons and never touched 200. To be fair to myself, only five Blue Jays ever got there. You know three already, now; the rest are guys I had forgotten about to some extent, or entirely. None of this is necessarily anything you'd need or even want to remember. But it has been my experience that you don't necessarily get any say in that last bit.