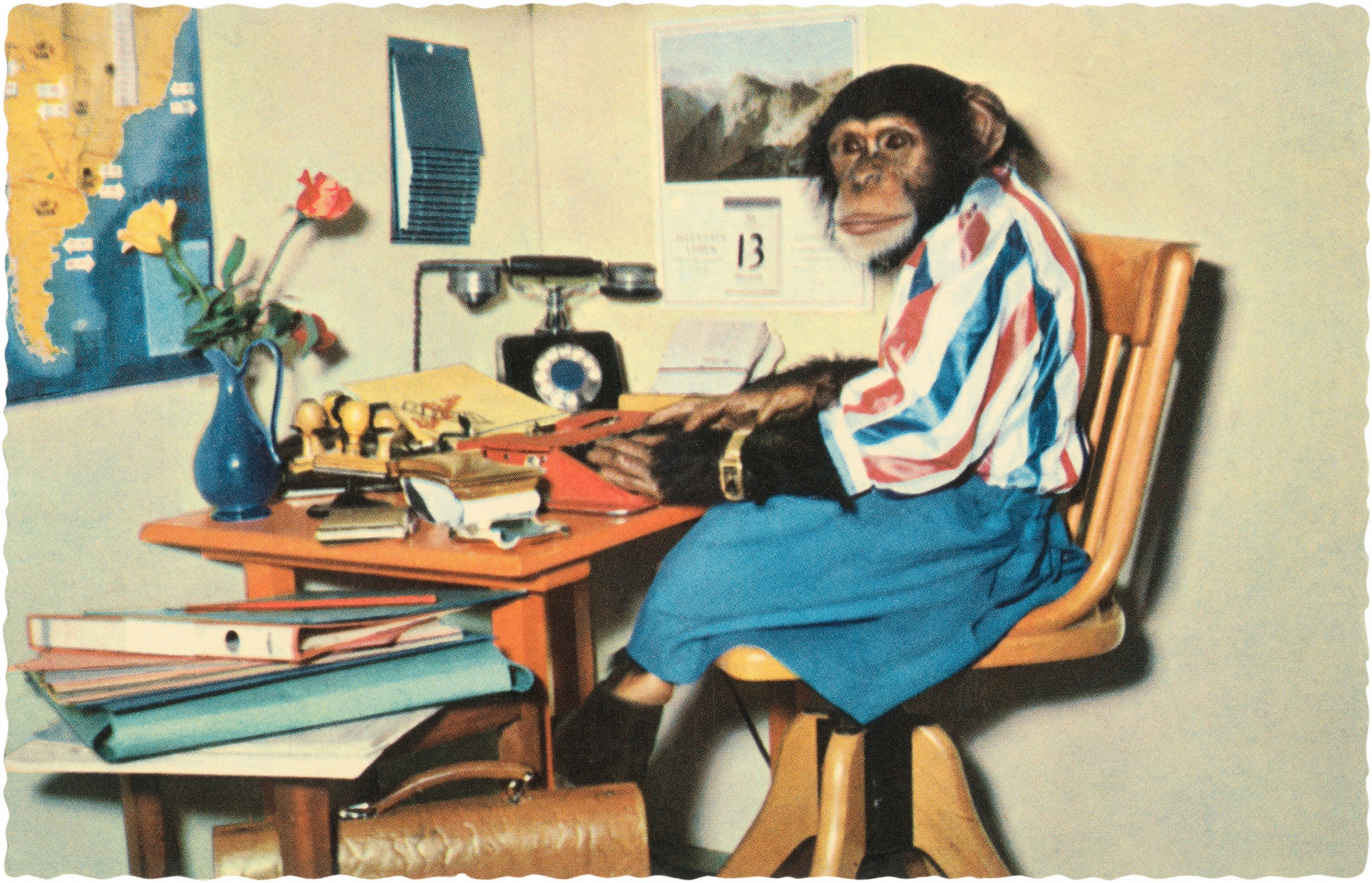

“Infinite monkeys at infinite typewriters will eventually type the complete works of Shakespeare.” Kathryn, with a degree in physics, absolutely hates this famous thought experiment. Barry, who thinks monkeys are funny, says it’s fine. We had them state their cases.

Point: These Monkeys Don't Have Pages, by Kathryn Xu

The infinite monkeys have had the most insidious impact on contemporary thought experiments of any math concept. People are out here saying that they can luck into a home run off an MLB pitcher. They’re saying that given infinite time, they can luck into a win against Garry Kasparov at chess! They’re saying that infinite monkeys can luck into a win against Garry Kasparov at chess!

Human beings are not good at processing big numbers. It takes some practice to even get good at Fermi problems, which are dealing on orders of magnitude within ready human comprehension. In the second edition of Charles Kittel and Herbert Kroemer’s Thermal Physics, they pose an operational representation of the monkeys with typewriters as a homework problem (pg. 53, c. 2, p. 4). Assuming that a typewriter has 44 keys, and that Hamlet has 105 characters, and that case sensitivity does not matter, the probability that any string of 105 characters will be Hamlet is 10-164,345, or 1 in 10164,345.

Look at that number, and weep. Can you even imagine what a 1 in 10164,345 chance looks like? For context, there are only about 1080 atoms in the universe. Assuming, as Kittel and Kroemer do, that 1010 monkeys type 10 characters a second for 1018 seconds (the approximate age of the universe), the probability that the monkeys will have managed to type Hamlet drops to a 1 in 10164,316 chance. Multiply the monkeys and characters per second and number of universes all you want; for any significant dent to the number, it'll have to be orders of magnitude past what the human mind can conceive. Imagine a billion universes whose atoms are typing monkeys, and it falls to a meager 1 in 10164,227 chance. Fathom that before making any unruly declarations.

I’ve mostly spared the math, but here it is in, uh, fine print. My professor in college tacked on a part C to the problem that asked for a gavel bang on the veracity of the thought experiment, to which I declared, "Not true!! Not true!! Everyone has lied!!" I have been going “i’m huffing and puffing im stomping and puffing i’m so mad” mode ever since.

But, you cry, Kittel and Kroemer aren’t operating from a mathematical sense of infinity. They’re operating from a quote attributed to Aldous Huxley in James Jeans’ 1930 popular science book The Mysterious Universe, that reads, “six monkeys, set to strum unintelligently on typewriters for millions of years, would be bound in time to write all the books in the British Museum”! What about infinity?

Well, what about infinity? The reason why Kittel and Kroemer operate on these constraints is because they work in the same field that helped birth the monkeys. When Sir Arthur Eddington referenced the monkeys, it was to contextualize the possibility of gas molecules violating the laws of thermodynamics, but—notably—was not used to declare that the gas molecules would do so. Eddington writes, “When numbers are large, chance is the best warrant for certainty … which does not always reward the expectations of those who court the fickle goddess.” He admires the whimsy of the possibility, but not by jacking up the number of theoretical monkeys until they succeed; there is no need to do such a thing when such a finely defined, numeric impossibility is admirable in its own right. Search furiously through Borges’s “Library of Babel” all you like, but we all have finite lives. In our human world, these monkeys don’t have pages.

Counterpoint: I Believe In The Monkeys, by Barry Petchesky

Human beings are not good at processing big numbers, but they’re even worse at processing infinity. Do you know how many things infinite things are? So many things. I don’t even know how to make those clever little superscript numbers, but imagine one of them here, like X to the Y, that looks like a really huge number. It’s actually even huger than it looks! But infinity is even huger than that. And not only it is huger, It’s infinitely huger.

We are not talking about 10 billion monkeys here. We are definitely not talking about the mere six monkeys they gave a word processor and did not end up producing Hamlet, or even Pericles. We are talking about infinite monkeys! With infinite time! They will eventually write the play, because they will eventually write everything. They will write plays Shakespeare only thought about and never wrote down. They will write plays that don’t exist yet. One fortuitous macaque will type out every Patrick Redford blog, verbatim and in order; another will type them but make them good. Many, many more monkeys will hit the spacebar repeatedly and get bored and mush their own feces into the keyboard. But they’re allowed to keep trying, forever.

I think that your STEM background counterintuitively has you being very rude to these industrious monkeys’ chances, while my had-to-take-math-in-summer-school-twice ass has a properly awed view of large numbers and of infinity. You’ve worked with these sorts of absurd numbers; you grasp the scale of the universe and of probabilities, scales the human brain does not naturally wrap itself around. You respect numbers, in a way that follows from understanding. To me they may as well have the aspects of a deity, for all their incomprehensibility—and their lack of application to my life.

But that is, to me, the entire point of the infinite monkey theorem. It’s not trying to impress the idea that we can gather enough monkeys and enough typewriters and they will actually, some eon, write a play; there are only so many atoms and thus potential monkeys in the entire universe, and only so much time before its heat death. It’s not trying to demonstrate anything about probability, really. The infinite monkey theorem is not applied mathematics (or literature). It is a thought experiment: a way of demonstrating the implications of infinity, that this thing that could never, ever, ever happen in our universe—because our universe is mind-bogglingly old and huge but not infinite—would happen under that condition. That it uses a simian example that helps a dummy like me start to grasp the shape and span of the unthinkable is evidence for its utility.

Lastly, and respectfully, mathematics still has its blind spots. Advances are made every day, which means there are still things we can’t explain, or can’t prove. We can sketch a broad charcoal portrait of the universe, but we cannot yet peer into its every corner. There may be no god of the gaps, but in those lacunae lie things we have no choice but to take on faith. Infinity itself requires faith that there’s no last number. And I have faith in the monkeys to write a nice play. They’re such silly little guys.