A lawsuit filed this week in the Superior Court of the State of California accuses Stan Kroenke, billionaire owner of Kroenke Sports & Entertainment, the holding company that controls the Los Angeles Rams, the Denver Nuggets, and Arsenal FC, of devising and executing "a devious and deliberate scheme" to rip-off fans of the Rams through "the fraudulent sale" of the dreaded personal seat licenses, which the Rams refer to as Stadium Seat Licenses (SSLs). The plaintiff, a man named Dwight Manley, says he was given bad information when the Rams talked him into committing over $900,000 toward six seat licenses at the Rams' Inglewood stadium, which is owned by Kroenke through a company called StadCo LA, LLC. Manley accuses Kroenke and his representatives of acting with "intent to deceive," and with "malice, oppression, and a conscious disregard" for the rights of SSL purchasers.

At issue is what precisely is meant by the word "sale" in a transaction of SSLs, why a person would be interested in "purchasing" personal seat licenses in the first place, and how a team navigates the delicate work of marketing a product that, on its face at least, appears to confer to the "purchaser" nothing more than right of first refusal on face-value tickets to home games, and at an extraordinary price. According to the lawsuit, Manley was in contact with Rams Premium Sales Consultant Andre Laws, the person who Manley says used a "litany of false representations" to sell him six SSLs between January and April 2021. Per the lawsuit, Laws contacted Manley in response to Manley expressing interest in seating options at what was then a brand new stadium. Not so long ago this would've meant walking through the price points of different season ticket packages for the upcoming season. For all the subterfuge certain franchises have used to juice season ticket demand, the packages themselves and the nature of the transaction were never very complicated. The benefit to the purchaser was a slight discount on tickets to home games, and of course the opportunity to resell tickets at a markup on the secondary market. The benefit to the team was essentially the same benefit that is enjoyed by Defector dot com when our best and coolest readers purchase annual subscriptions: a nice chunk of operating revenue becomes recognizable throughout the year.

The standard season ticket transaction was simple because there was something close enough to an actual sale taking place. A season ticket purchaser did not own their seat(s) in any meaningful sense, but to the extent that the privilege of resting one's buttocks in any given seat for the length of one football game was granted only to the holder of a corresponding ticket, the fan who had purchased said ticket owned that privilege, and had approximately as much autonomy as a fan could reasonably want from that arrangement. The same cannot be said for the holder of a personal seat license, at least not in the case of the Los Angeles Rams, whose SSLs are modeled more or less on PSL trends across professional sports. The holder of a Rams personal seat license has not gained ownership of anything. In fact what they have gained, more than anything, is an obligation.

In May 2017, about six months after ground was broken on the Rams' Inglewood stadium project, a D.C. law firm filed paperwork with the Securities and Exchange Commission's Division of Corporation Finance on behalf of a Delaware-registered non-profit known as LA FanClub Inc, seeking permission for LA FanClub Inc to sell different tiers of membership to fans of the Los Angeles Rams, who'd relocated from St. Louis a year earlier. LA FanClub, established in March 2016, described itself as a "membership organization for the Rams' loyal fans" that had as its mission "to be a strategic and significant part of the building and strengthening of a Rams fan base" in southern California. Fans could join FanClub by signing an agreement and paying a "small one-time non-refundable initiation fee." Memberships were broken down into two types: The lower tier, which has the quaint distinction of being comprehensible in the context of something propped up as a fan club, is referred to in the filing as the FanClub Non-PSL Membership, and gives Rams fans access to certain organized fan events—think draft parties, tailgates, fantasy camps, and so forth. The upper tier is referred to as the FanClub PSL Membership, and it gives its members all that same cutie-pie crap while also entitling them to purchase seat licenses.

This FanClub arrangement is referred to in Manley's lawsuit as a "Fanfaire Membership Agreement," and it represents the first step toward gaining tickets for Rams home games. Manley paid money to initiate this non-refundable membership agreement on Jan. 31, 2021, which entitled him to proceed to the second step of gaining tickets for Rams home games, which is "a Los Angeles Rams Stadium Seat License Agreement," which also costs money. In this January round Manley signed on for four PSLs, which ran him a cool $400,000. Had Manley now gained tickets for Rams home games? No. What he had gained, according to the FanClub filing, is "the priority right to purchase season tickets to Rams home games," at face value. Where the filing uses the word "right," it is more appropriate to think of it as an obligation: According to the SEC filing, seat license holders who decline to purchase season tickets by specified dates will forfeit their licenses, although their FanClub memberships will continue to gain them access to the fantasy camps and whatnot.

Why would a person do this? For starters, this is increasingly just how season tickets are sold, a new and ultra-expensive cost of doing business. But PSL holders talk themselves into these purchases in part because there exists a secondary market for PSLs, where demand for PSLs is satisfied by people prepared to offload their PSLs, often at a significant profit. The Baltimore Ravens, for example, have a link on their official website guiding visitors to an official Ravens PSL marketplace, where transactions are reviewed and approved by the Ravens organization.

Manley, according to his lawsuit, was interested in a Rams PSL as an asset with appreciating resale value at least as much as he was interested in scoring bitchin' seats to Rams games. In screenshots of text messages attached to the suit, Laws appears to confirm for Manley that the team will operate a "website for resale" where Manley can sell his PSLs "for whatever dollar amount you'd like" at any point after the first year of "ownership." Manley, who expressed interest in the priciest PSLs due to their exclusivity, hoped that his PSLs would soon become "significantly more valuable to future purchasers on the promised online 'marketplace,'" according to his lawsuit. As it happens, the Rams went on to win the Super Bowl, in their home stadium, one year and 13 days after Manley executed his first round of PSL agreements. For someone whose purchase of expensive PSLs was essentially a speculative investment, this would seem to have been a huge score.

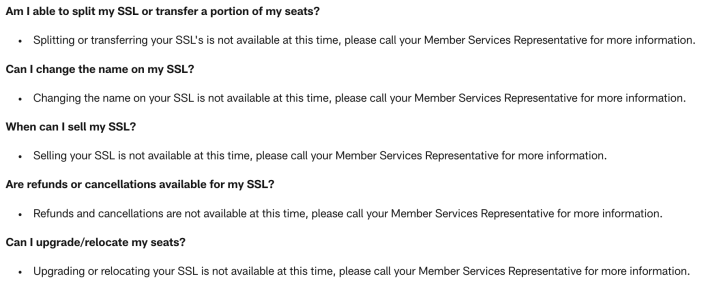

This is where things get complicated. For one thing, as is the case with the Ravens, the Rams retain "sole discretion" to approve the transfer of PSL Memberships to third parties, approval that must be sought via a written application and which comes with its own associated fees. But more importantly, the "website for resale" referenced in Manley's texts with Laws does not yet exist, and Rams PSLs are not yet transacted on STR Marketplace, the website used by the Ravens, along with 20 or so other franchises and venues, including 16 total NFL teams. Perhaps due to their lack of a formal marketplace for PSL transactions, the Rams do not yet allow for the sale or transfer, or even for the upgrading or relocating, of existing seat licenses. Two-plus years into the operation of their shiny new stadium, the Rams' seat license program appears to be a bare-bones operation that does not yet confer the real ownership benefits that make the expense of a PSL arrangement anything even close to a sane and defensible addition to the cost of season tickets.

So what is a "loyal fan" of the Rams to do when he learns that his million bucks worth of seat licenses—Manley executed a second round of PSL agreements in April 2021, for the right to purchase an even more expensive and exclusive pair of season tickets at Rams home games—cannot be flipped on the secondary market at the precise moment "when the value of [Rams PSLs] presumably would be the highest," or indeed at any point in the foreseeable future? Naturally he comes calling for a refund, because if we are being honest only a moron would fork over a million dollars for the right to fork over tens of thousands of dollars per season for seats scattered all over the stadium of the Los Angeles Rams, without some expectation of somehow turning a profit.

Here is where this shit gets even more complicated: The SEC filing makes it very clear that all FanClub PSL Members are entitled to refunds of the cash they invest in seat licenses. That is because the money that is paid for a Rams PSL is considered a deposit. Money from the accumulated deposits of PSL holders is socked into an account controlled by Stadco, and Kroenke, as the owner of Stadco, is required to vest money in a "defeasance fund" which will eventually cover the cost of refunding all the PSL deposits. So Manley is entitled to a refund, and the money exists to give him a refund. But the lesson, as always, is that you should always check the fine print. From the FanClub SEC filing outlining the Rams PSL program:

Under the PSL Program, each purchaser of a FanClub PSL Membership will beentitled to a return of the refundable Deposit, but such repayment will be madewithout interest and will not occur for fifty years.

LA FanClub No-Action Letter, May 2017

Worse, when Manley reached out to the Rams seeking his refund, he was told that in addition to having to wait half-a-century for his refund, he was obligated under the terms of his agreement to continue making payments on his six PSLs toward the approximately one million dollars he'd committed in his two agreements. While the FanClub filing makes clear that a PSL holder may forfeit their membership rights by declining to purchase season tickets, nowhere in there does it expressly state that a PSL member can pull up short of making their full refundable "deposit," which is the thing that entitles them to purchase the season tickets that they no longer want.

Continuing Obligation to Pay the Total Deposit Payment. Notwithstanding any termination of any or all of Licensee’s SSL(s) or this License Agreement, Licensee shall continue to be liable for payment of the Deposit amount in full, as set forth in Exhibit B.

Manley's Complaint

Manley may indeed look forward to securing that refund—scheduled to arrive in his bank account in 2068—but in the meantime he is expected to continue making annual payments, plus a non-refundable eight percent fixed interest rate, until the full amount has been deposited with FanClub, and thus Stadco, and thus the Rams, and thus their billionaire owner. Calculating for the lost interest and the time value of money and our present runaway inflation, it would appear that Manley is pretty well screwed.

Manley says that he never would've entered into this arrangement in the first place if Andrew Laws, acting on behalf of Kroenke, had not misled him with "patently false statements" about the details of the arrangement, in particular the establishing of an official marketplace for the resale of Rams PSLs. Manley says Laws told him he could resell his PSLs after one year, and that he could decide at any time to discontinue making payments, and that his PSL agreement would confer genuine ownership, when in fact none of that appears, at present, to be the case. He is asking the Superior Court of California to reward him "damages that he has suffered as a result of the scheme and other relief to which he is entitled," and in an amount "sufficient to deter Defendants from engaging in similar behavior in the future."

If this all strikes you as insane, that's because it is. Personal seat licenses are a method of financing that only works because of how teams confuse and veil the terms, in the best of cases winkingly offering to wised-up speculators a minimally regulated investment vehicle masquerading as priority access, in the worst of cases outright deceiving susceptible fans about the real-world value of that priority access, and in all cases stretching the definitions of words like "sale" and "purchase" to the absolute breaking point. A California court will decide whether Kroenke and the Rams technically violated the letter or spirit of the team's PSL agreements, but the entire enterprise is established in bad faith and is at best the second yuckiest vehicle for stadium financing. Manley's complaint is embedded below, for your perusal.