Like regret and interest, small problems compound. They lie on top of each other tiny but heavy, until one of them—meaningless on its own—breaks you. Yesterday, it was balsamic vinegar. I was tidying the kitchen: the most mundane of my chores and also the most terrible because I hate doing it. The counters were wiped, the backsplash cleaned, the coffee grounds emptied, but there was a canister of salt still on the counter. It needed to go to its home inside the corner cabinet with the other spices and jars.

I spun the cabinet open, dropped the salt in a little roughly, and pushed the cabinet closed. It swung. It does this a half-dozen times a day without issue, but yesterday something caught. The edge of the spout of the fancy balsamic vinegar clipped an edge on its way around and tumbled to the ground. It shattered, the big jagged chunks of glass dulled by the pooling black liquid. It was thick like blood and spreading, a puddle that could cut.

On its own, this is a small problem. It was cleaned up—the shards plucked carefully from the goop and placed into a bowl, the delicious vinegar shoveled into a dust pan and dumped, the floor mopped. But the vinegar was the second thing that I loved that I broke yesterday, on my day off, at the end of a long, exhausting week where I wrote a lot for work and not at all for me, and it was just enough to snap me.

The sharp, sweet scent of the spill is still in the kitchen. It is lingering, taunting me. This is not a real problem, of course. I can buy another balsamic vinegar. But looking down at the spreading puddle, hearing the thump of footsteps on the stairs after the crash, I could feel the moment embedding itself in my mind, the memory writing in ink. In ten years, probably, I will eat a beautiful caprese salad, smell the balsamic and remember this unimportant Saturday afternoon failure. It's here to stay, for whatever reason.

I've been tuned in to the small sticky moments lately because I've been reading the work of Tove Ditlevsen again.

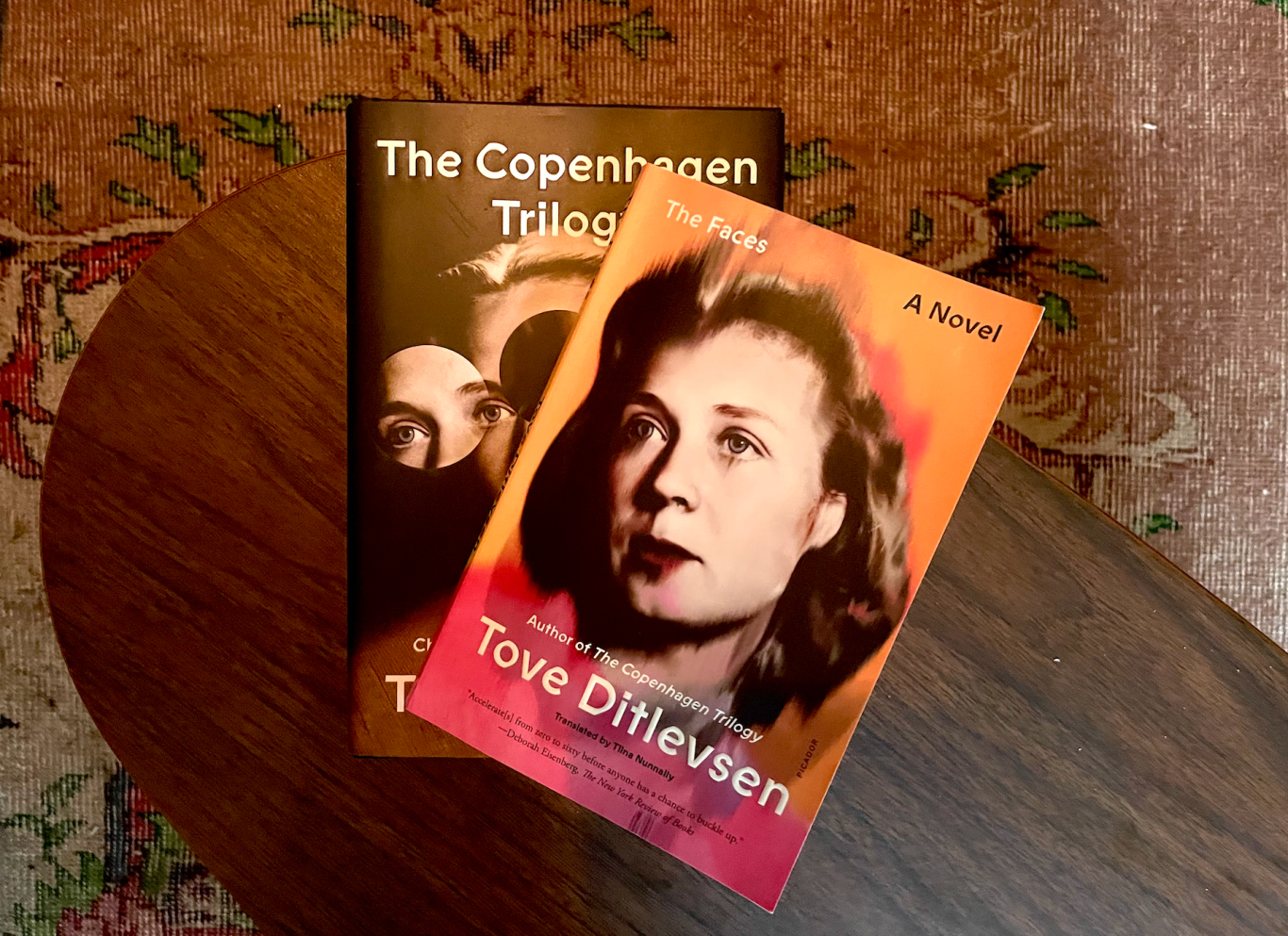

Ditlevsen was a Danish writer. She was immensely popular during her lifetime among women and not at all among men. She published 29 books of memoir, poetry, fiction, and short stories. And unlike many of the great memoirists that I love like Karl Ove Knausgaard and Annie Ernaux and Elena Ferrante, Ditlevsen isn't so interested in takeaways. She does not present her work with a guiding moral or philosophy. In fact, it feels like she intentionally veers away from self-revelation every chance she gets. She wrote in The Copenhagen Trilogy that writing was a way of placing a “veil between myself and reality.”

I've been turning that phrasing over in my head for almost a year now. I read Ditlevsen's The Copenhagen Trilogy the week it was reissued in English last year. I had anticipated it for a few years since reading contemporary Danish novelist Dorthe Nors's story about her in The Second Shelf. Nors wrote that there was a "distinctive tone that Ditlevsen emits in her bittersweet swoops above humanity. [...] Women have heard that tone in her poems from the outset. We know it. It sings from deep within us."

I read her work as soon as I could. I devoured a strange, out-of-print book of her poems the bookseller found for me. I chugged The Copenhagen Trilogy, breathed, and then read it again. I returned to it over and over again for its beauty, for it's analogies, for Ditlevsen's breathless ability to portray the world as a place that can poke you: the surprise the fore-feeling before you reach pain. Ditlevsen is self-critical, self-deprecating even, and ferociously talented. "Childhood is long and narrow like a coffin, and you can’t get out of it on your own,” she writes in the first book of the trilogy. “It’s there all the time and everyone can see it just as clearly as you can see Pretty Ludvig’s harelip.” She is a master of the one sentence backstory: "When Asger left her ten years ago, he had left behind a storehouse of words and ideas inside her like a forgotten suitcase in a left-luggage room at the train station," she wrote in her 1968 novel The Faces. Her poems are small revelations of truth, little observations we see through her eyes:

An old lady

stood next me

under an open umbrella.

The skin on her neck

looked like a turkey’s.

I wished I

were her

because she

was nearer death.

excerpt from "Self-Portrait 5" by Ditlevsen

The marketing around her books is always about her as a person, but her writing is the reason she's remembered at all. I am not writing here about her personal life, because who she was as a person is less important than her voice on the page. As Lauren Oyler wrote in Harper's last year, "Ditlevsen does not fit neatly in the lineage of hot messes whose writing can only be appreciated in light of their unjustly female circumstances and put-upon psyches; she was a writer first and a mess second."

I have been reading several of Ditlevsen's now out-of-print titles that I have procured through dubious means and marveling at how much of herself she gives to her work. At times, it is obvious how hard she is trying to build something beautiful, but most of the time it feels effortless. Every metaphor is a skyscraper she tries to build as high as possible, every analogy she attempts is a half-court shot. And most of them, she makes.

Here is a quote by Annie Dillard, another great writer, that I tacked up on the wall a couple of weeks ago:

"One of the few things I know about writing is this: spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes."

Annie Dillard's The Writing Life

If anyone spent it all, I thought when I first found this quote, it was Ditlevsen. It is rare, as a reader, that you can feel her effort, but it's there. She's straining not against a society that hates her (she was beloved by Danish readers during her lifetime), but against herself. She's trying to figure out what it is she needs to say, what kind of veil can be placed between herself and the world to distort it until it's manageable.

"The world doesn’t count me as anything and every time I get hold of a corner of it, it slips out of my hands again,” Ditlevsen wrote at the end of Childhood. That's the goal of writing, I think. Not to grasp the world and hold it still and securely forever, but to attempt just for one second to grab a corner and see clearly what it looks like before you let it go again.