Punchbowl, a media company launched earlier this year by a few former Politico staffers, has been the subject of some breathless media coverage lately. Over the weekend, the Wall Street Journal broke a bit of news about Punchbowl in an article about promising new media ventures. From the report:

Punchbowl News has attracted more than 100,000 subscribers since its January debut, [Punchbowl co-founder Jake] Sherman said. The company—which employs eight people and has raised $1 million from investors including LionTree LLC’s Kindred Media—is on pace to generate more than $10 million in revenue this year, according to a person familiar with the company’s finances.

One hundred thousand subscribers sure is a lot for a company that's been around for less than a year and only has eight employees. And $10 million in annual revenue is nothing to scoff at, either. As no other information about Punchbowl's business model is included in the story, the WSJ's framing seems to suggest that this revenue is coming from subscriptions, or people who pay to be Punchbowl "members." This is an idea Punchbowl's own branding encourages; the company sells itself as a "membership-based news community."

But yesterday, Axios complicated this narrative a bit. While claiming that the company "is on its way towards building a small D.C. empire," Axios revealed approximately how much of Punchbowl's revenue paid subscriptions account for:

The memo confirms a Wall Street Journal report that Punchbowl will bring in more than $10 million in revenue in 2021. The company says paid subscriptions account for more than $1 million of its total revenue. The company also sells advertising and events.

So if Punchbowl's claim that it has 100,000 subscribers is accurate, but it only makes around $1 million from subscriptions (which cost $30 per month or $300 per year), then that means only a very small fraction—somewhere around 3,000—of those subscribers are paying actual money for Punchbowl's primary product. (Note the squishy phrasing of "more than $1 million of its total revenue"; Punchbowl declined to break out exactly how much more than $1 million.) The rest must be signed up for Punchbowl's free product, which includes one daily and one weekly newsletter. Those who do become paying subscribers get three newsletters a day, which frankly seems like too many, as well as additional content including a Sunday night "show," plus "invites to small member-only dinners, cocktail hours, newsmaker interviews and New York, D.C. and West Coast parties and networking events."

The Axios story also notes that Punchbowl "sells advertising and events." If only about $1 million of Punchbowl's revenue is coming from paying subscribers ("members"), that means "advertising and events" account for the vast majority of the $10 million in revenue it claims it will make in 2021. Events can certainly be a lucrative stream of income for news organizations. However, when I asked Sherman about Punchbowl's events business, he told me that all of Punchbowl's 13 events this year—which included conversations with White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain and Senator Chris Coons—were free to attend.

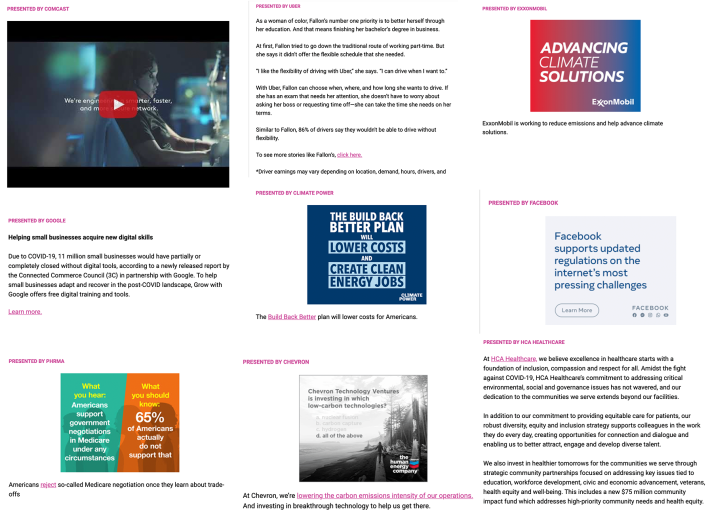

This brings us to advertising. Sherman declined to provide a breakdown of how much of Punchbowl's non-subscription and non-events revenue comes from selling ads, but it's fair to assume that number is quite high. Each Punchbowl newsletter and most Punchbowl events feature a sponsor. For example, one "Road to Recovery" event from July was sponsored by Goldman Sachs and also featured Goldman Sachs' CEO David Solomon as a speaker. An inexhaustive list of newsletter sponsors from recent months includes: Exxon, Duke Energy, Google, Uber, Comcast, Chevron, Facebook, PhRMA (a drug company that advocated against Medicare drug price negotiation during the fight over the reconciliation bill), and Climate Power (a Biden administration-affiliated communications firm). Sponsors, of course, are the same as advertisers.

Media companies need to make money, and if the backbone of Punchbowl's revenue strategy is creating newsletters and holding events that serve as billboards for powerful companies and lobbyists to get their talking points in front of D.C. swamp creatures, then more power to them. But it's strange to see Punchbowl written up in the Wall Street Journal as a kind of novel, booming subscription business—perhaps reporters and editors need to become more diligent about marking the difference between paying and non-paying subscribers—when it's just a carbon copy of so many other ad-supported media concerns.

The media industry is in shambles. As a result, there is a lot of attention to be gained by anyone who can present a new way of doing things. You've certainly read more than you ever cared to about Substack (or, uh, Defector) by now. But behind all that attention, there's something kind of funny happening: People who are just doing the same old shit are adopting the key buzzwords and poses born out of recent trends in an effort to make it look like they too are doing something innovative. It might be accurate to say that Punchbowl has 100,000 daily readers (though of course many people never even open email newsletters), but that's so 2012. Much better to say it has 100,000 subscribers. You might say that The Atlantic just hired a slate of new columnists who will go about publishing columns in the magazine and on the website, but whose engine is that going to rev? Why not instead hype those new columns as subscriber newsletters?

The problem with this sort of framing is that it makes it harder to notice that the media industry is, broadly speaking, still standing where it always has been: in a place where the old structures persist and survival is still dependent on the whims of various billionaires and tech firms.