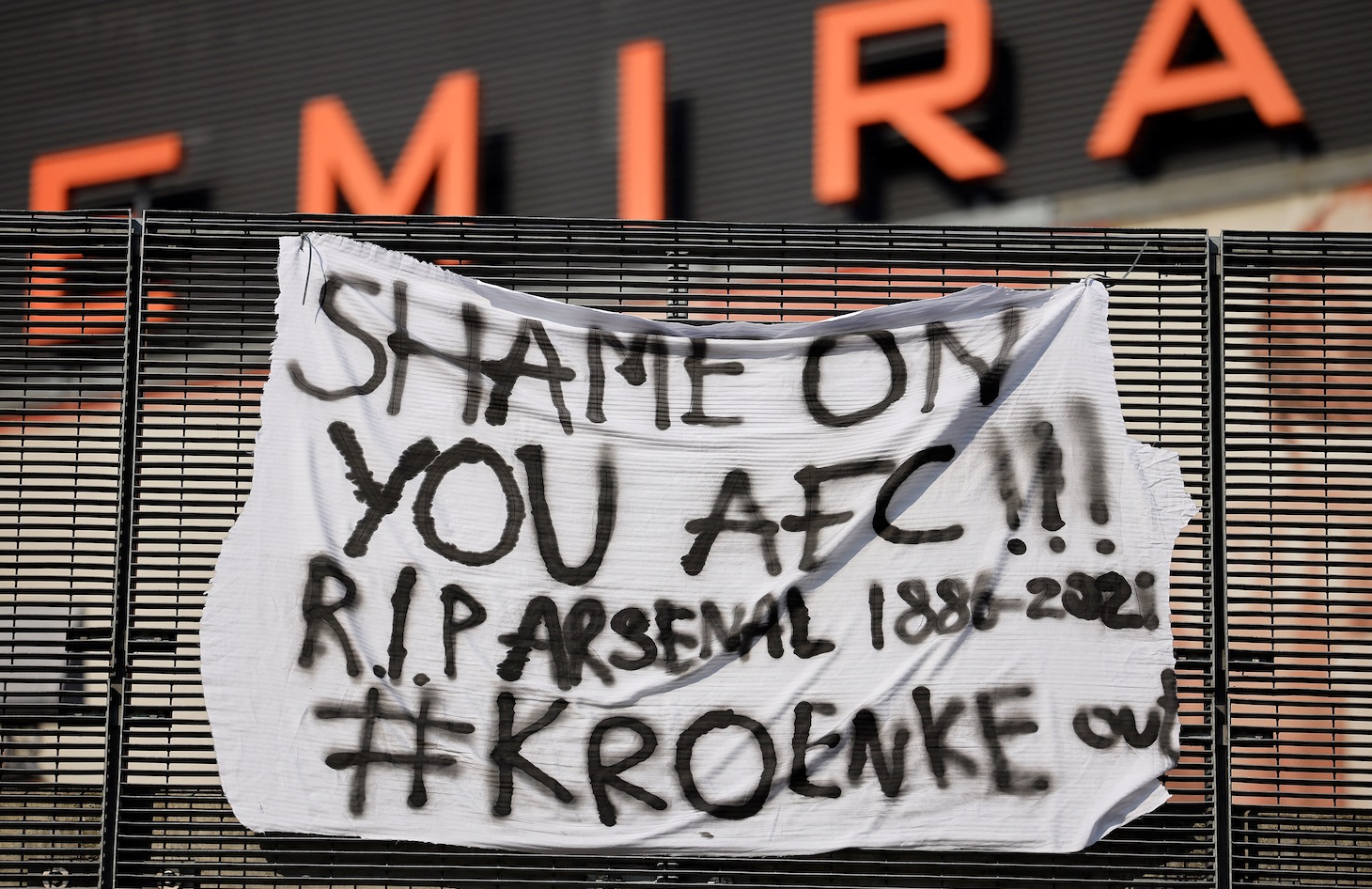

The first and only real takeaway from Comrade Haisley's thorough-as-can-be analysis of the European Super League is that it is indeed evil, but there is one bit of further proof. The analysts from across the pond are describing this as based on "the American model," and continually cited both Stan Kroenke, who owns Arsenal, and the Glazer Boys, who own Manchester United, as particularly eager to sign on to what seems to be La Liga's biggest clubs' grand escape from the perilous financial straits into which they have boldly sailed.

And it's not just "the American model," but the way they say it: with particular stank on every syllable because they see the NFL model all over it, as in Kroenke (Los Angeles Rams) and the Glazers (Tampa Bay Buccaneers). Liverpool is also part of the Super League and is owned by American John Henry, but he only owns the Boston Red Sox, and make of that what you will.

The Super League is basically the mechanism by which 12 prestigious English, Spanish, and Italian clubs get to be in a massively lucrative competition without having to do anything except not fold. There is no qualifying, no danger of relegation, no inclusion or exclusion by merit of any kind. It is ironclad revenue-and-cost certainty, as though Jerry Jones got the Dallas Cowboys into the NFL playoffs every year because he is Jerry Jones—which has usually been the reason why the Cowboys DON'T get into the postseason, but that's a digression for another time. The Super League is simply a lucrative competition without qualifications other than "Here I am, worship me!"

In that way, the Super League is just heightening the contradictions. Teams are very much already treated differently based on market size and popularity, the evidence found mostly in network broadcast windows and merchandise priorities. The Cowboys matter more than the Lions, the Lakers matter more than the Kings, the Yankees and Red Sox matter more than everyone else, and if we ever declare war on Canada, the Maple Leafs will be hockey's version of America's Team. They split all the national money, and each team gets a share. That profit-sharing is the part the Super League owners are especially looking forward to—only after they start their own secret club without any Crystal Palace or Fulham dragging down the balance sheets.

Think of it the way you would view the National Basketball Association, only with the Lakers, Celtics, Knicks, Heat, Mavericks, Clippers, Bulls and an eighth team invited so the first seven can poach its best players. They would still play their regular NBA schedule and get their chunks of the national revenue but also play in a separate league simultaneously and with a separate revenue stream. They'll take Memphis out to dinner, but they also intend to take New York City to the theater and Miami to bed. They decide they're special, they convince you they're special, and what they win is a special place in your wallet.

And you're not surprised, no matter how pissed off you are. America invented sports label shopping way back when, and is burning tradition and the concepts of partnerships and shared risk/shared reward like so much dried brush. The college football conference realignment was a less ambitious version of the Super League, and the next round is very definitely going to separate the Oklahomas from the Iowa States, the Ohio States from the Indianas and the Alabamas from the Vanderbilts because longstanding mutually beneficial relationships are for the weak. We might pretend to abide a version of Leicester City winning the Super Bowl as a 5,000-1 shot, but if the name was changed to the Detroit Lions, you'd wonder if the games were fixed. In the Super League, the competition is fixed from the start and you know it because they already told you.

This is basic economics based on sheer brute force; like the Brits said, "the American model." It's lazy and inelegant and snobby and brutish, but it is also risk-averse. It's frankly a league in which the games don't really matter because they carry no consequence. It's like the Yankees or Bulls finishing their current seasons the way they are and then holding a parade for being in the league the next year, too. Before, that was called paying your dues; now, apparently, it's called winning.

But is it interesting? Who the hell knows? Soccer fans are unbearable snobs too; they talk about the joy of the game's structure and the year Leicester won it all, but ain't nobody you know going to wake up at 4:30 a.m. to watch Norwich City or Sporting Gijon. It's just an elaborate version of building a treehouse you share with the neighborhood pals and then going across the street to get a new one built in a bigger tree with different friends from another neighborhood. You still get to hang in the old treehouse, but that new treehouse has 15 rooms and marble floors and a gym and a world-class kitchen and an Olympic pool and a 300-seat theater that only 12 people have the keys to, and your old friends can't go to that one. And then, after you've pulled that off, you talk about the new treehouse, the love you have for the old one and, oh, this just happened: because you have two treehouses you're now a considered a world-renowned botanist.

It's despicable. It's cutting edge. It's how the megarich got megaricher during a global pandemic. It's capitalism at its end stages only less elegant, and it comes with watching Andrea Agnelli of Juventus and Liverpool's John Henry exchange heartfelt greetings at the start of their new venture while simultaneously thinking, "How can I steal what that guy's got?"

Yep. "The American model," all right. I'd recognize it anywhere, because it's everywhere.