In 2021, a group of sightseeing geologists were touring the Bhimbetka Rock Shelters in central India when they noticed something high up on the walls. There were grooved impressions, just a few centimeters long, that looked almost like a leaf, with veins erupting from a middle line. The impressions were too high on the cave wall to directly sample, so the geologists photographed the spot and analyzed it in 3D back in the lab, according to a story in The New York Times.

Gregory Retallack, a paleontologist at the University of Oregon, and his colleagues identified the impressions as the fossilized remains of Dickinsonia—a creature that looks like a thumbprint—and published their findings in the journal Gondwana Research.

Dickinsonia is frequently called one of the most iconic and controversial members of the Ediacaran biota—the creatures that occupied Earth starting around 635 million years ago. There were no predators yet, so all life was soft and gooey, shaped like a tube, a frond, or even a pillow—it was a time when the ridgy appearance of a thumbprint certainly might have been iconic. Scientists speculated if Dickinsonia was an animal, a protist, a lichen, or even a colony of bacteria until the geochemist Ilya Bobrovskiy isolated molecules trapped inside a Dickinsonia fossil and confirmed it was indeed a creature.

Up until that point, Dickinsonia had only been found in rocks in south Australia and north Russia. Its presence in India seemed to expand the whereabouts of some of the earliest animals on Earth as well as settle a debate about the age of the rocks at Bhimbetka. The discovery even offered insight into the environment of the supercontinent Gondwana, which held the future India, Australia, and Antarctica.

Unfortunately, this ancient and potentially revelatory putative fossil has been unmasked by a new team of scientists as, well, bees. Specifically, it is the decaying remains of a giant honeybee hive—according to a new paper in Gondwana Research titled "Stinging News: ‘Dickinsonia’ discovered in the Upper Vindhyan of India not worth the buzz."

Joseph Meert, a geologist at the University of Florida and author on the buzzy new paper, has been arguing for years that the rocks around Bhimbetka were about one billion years old—much older than some other estimates. His team's analysis of the radioactive decay of nearby, similar rocks suggests the entire basin is about a billion years old. "Rocks remember where they were formed," Meert said. "If we can get radioactive minerals from those rocks, then we can figure out how old they are."

But the reported discovery of a 550-million-year-old Dickinsonia "pretty much killed that idea," Meert said. So he returned to the site with Samuel Kwafo and Ananya Singh, graduate students in his lab, as well as Manoj Pandit, a colleague at the University of Rajasthan in India.

The team planned to spend several days around Bhimbetka looking for more Dickinsonia fossils. If they found any, it would mean that Meert's longstanding one-billion-year hypothesis was wrong. But when the researchers arrived at the caves in December of 2022, something was clearly amiss. The fossil did not appear to be a fossil. They actually had trouble finding it because most of it was missing—quite unusual for a fossil that had supposedly survived for about 550 million years.

"It took me about 30 seconds to become very suspicious of it," Meert said.

The most troubling detail, however, was that the fossil was placed at an angle. "When things fall and are dead, they fall onto the seafloor and rest there," Meert said. If a Dickinsonia died at the site, it would not be fossilized at an angle, cutting through layers and layers of sediment.

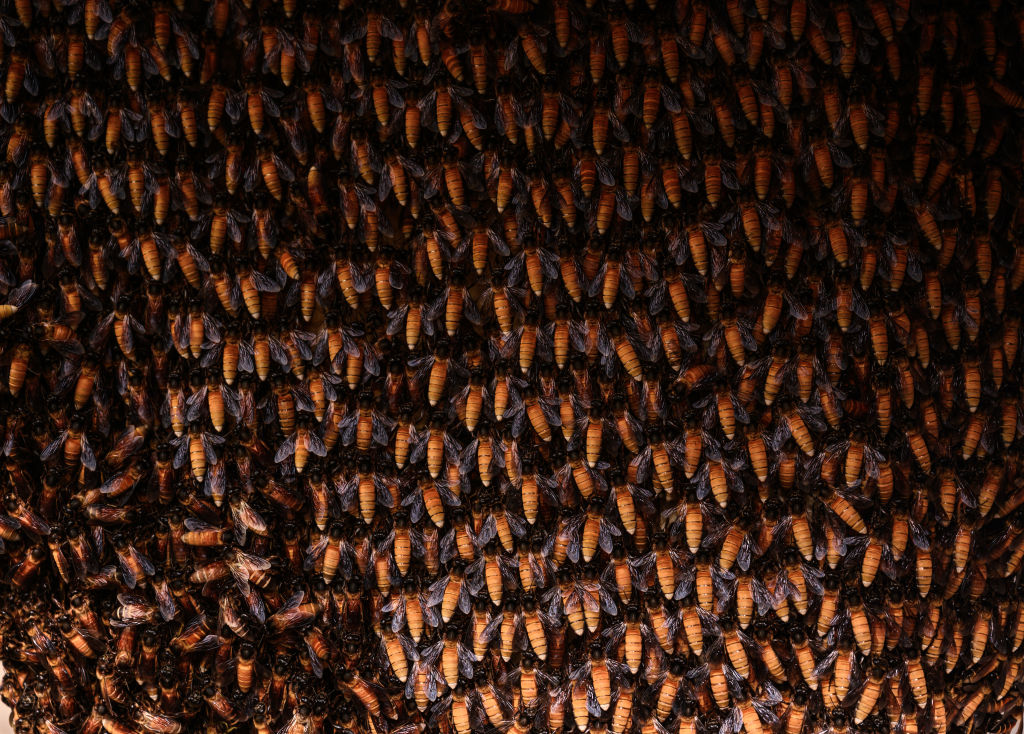

As the researchers looked around, Meert noticed the cave was full of giant bees nests positively bristling with bees. Some abandoned beehives appeared to have similar outlines to the fossil claimed to be Dickinsonia. He wondered if the Dickinsonia might simply be a decaying beehive. The scientists walked around the caves and took photos of all the bees nests they saw, including hives still in use and hives long abandoned. Meert remembered his son had taken a beekeeping course from Cameron Jack, an entomologist at the university, and he sent the photos to Jack, who confirmed the fossil could have an apian origin. "When we enlarged some of our photos, we thought, case closed, this is not a fossil," Meert said. When he enlarged the original photos taken from paper identifying the impression as Dickensonia, he could see hexagonal structures within the fossil—vestiges of honeycomb from bees long gone.

Retallack, one of the researchers who identified the beehive as Dickinsonia, agrees with the new findings, Meert said.

Fossils are mistaken for other fossils all the time. Tibias turn out to be femurs. Dinosaurs turn out to be lizards. This algae turned out to be a fish (after being reclassified as a cephalopod). It seems far more unusual for a fossil to be unmasked as a beehive. And, sure, bees might seem less exciting than the unexpected discovery of one of the earliest complex creatures to roam the planet. But I see this misidentification as a testament to bees, creatures that leave such extravagant and orderly traces that they can fool a group of scientists into rewriting the history of a subcontinent.

If Dickinsonia was one of the most iconic creatures of the Ediacaran era, bees are one of the most iconic creatures of our modern era. It is an honor to be tricked by them. If something close to you is not what it seems, ask yourself, could it simply be bees?