I received a Kindle Scribe for Christmas last year, which I probably should have expected, on account of asking for it. The Kindle Scribe is, basically, a large e-reader, with a stylus. It came out late last year. I put it on my wishlist because I was curious about it, but not curious enough to buy one for myself.

I am a fan of the Kindle e-reader line, though. (I have heard Kobo e-readers are quite good if you wish to be free of Amazon’s ecosystem and whole evil deal, but I have never used one, and also Kindles last forever so I haven’t needed to replace my quite old one.) My ideal reading setup is to keep a physical copy of a book at home and borrow the ebook version from the library for bars and restaurants and train commutes. (Bless Verso Books, by the way, for including a free ebook with nearly all of their print books.)

What is immediately apparent about the Kindle Scribe is that it is a neat little device and also almost extraordinarily useless. It is a very good oversized e-reader, but there are simply not many uses for an oversized e-reader. Being too large to fit in a coat pocket or to comfortably hold one-handed on a crowded train, the Scribe is not at all conducive to the things one uses an e-reader for. Of course, its selling point is not its size, but its stylus—a Kindle you can write on!—so it is a bit disappointing to report that Amazon could not figure out why one would want to write on a Kindle.

With the Scribe, you cannot write directly on ebooks, only leave “sticky notes” on them. It has numerous “notebook” templates, but all you can do with the notes in your notebook is email them to yourself as PDFs. The Scribe has no handwriting-to-text features. (Considering that I was using a stylus to write words that a handheld device automatically converted to text on a hand-me-down PalmPilot from my dad in 1998, this is a fairly bizarre omission.) The only documents you can freely scribble on are, as far as I can tell, PDFs. But PDFs are really the thing’s strong suit already. With its much larger screen, the Kindle Scribe already handles text-heavy PDFs better than its smaller siblings.

So the Kindle Scribe is, basically, a device for reading, and doodling on, PDFs.

Thankfully, there are plenty of PDFs out there in the world for one to read. There are samizdat or quasi-legal (or even sometimes fully authorized and legitimate!) copies of out-of-print books, like the leftist economic analyst Doug Henwood’s Wall Street, which is available for free on his website as a PDF. There are weird old journal papers and scanned archival documents. Just a whole world of things I can now more comfortably read in bed than I could before. And scribble on.

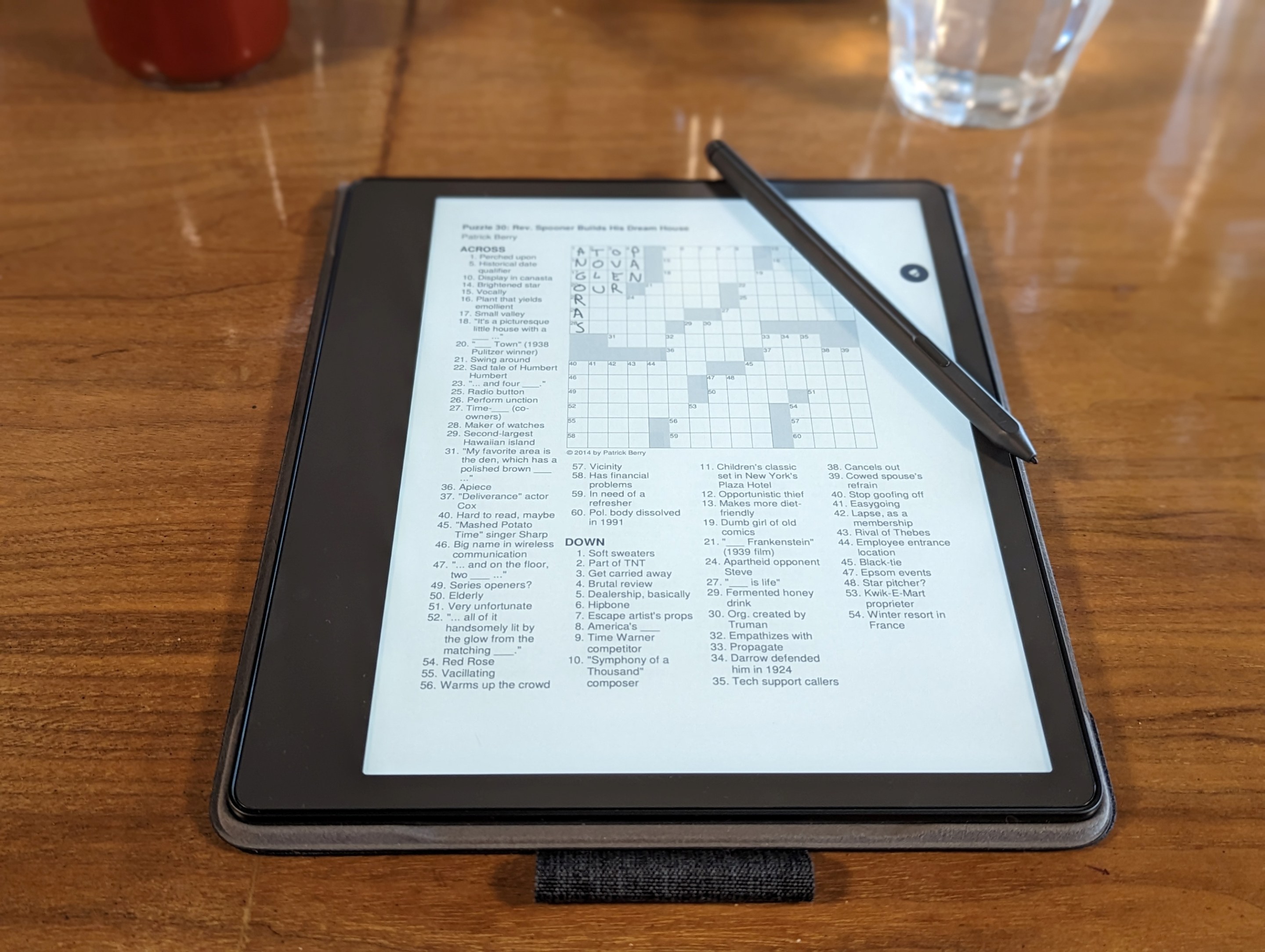

So I have been using my Scribe mainly to read PDFs, and rarely to write anything. Recently, when I finished the NYU Transit Costs Project’s Final Report and New York Case Study—two instant classic PDFs, highly recommended—I ended up turning to the veteran crossword constructor Patrick Berry’s “Crossword Constructor’s Handbook,” which used to be a “For Dummies” book but which is now available for purchase directly from him as a PDF. The book comes with 70 sample puzzles. As I read the book’s first chapter, I noticed he very shortly began making reference to those sample puzzles. So I opened up the accompanying document. And as I grabbed the stylus and got to work, I rather quickly realized: This is what this strange device is for. This is what it’s good at.

I grew up doing crosswords in the actual paper, with an actual pen, and while, at this point, I have probably solved thousands more puzzles on my phone than I ever did in print, I still always feel like solving them with pen and paper is the “proper” way to do it. The Kindle cannot check your answers as you go, or time you, or play a little jingle to announce that you have completed a puzzle successfully. It cannot helpfully fill in an answer you are struggling with; if you want to cheat, you will have to cheat the old fashioned way, by looking something up or peeking at the answer grid. But the Sunday paper can’t do any of those things either, and that is the medium the crossword was designed for.

The Scribe has all the benefits of paper puzzles—easy display of unorthodox theme grids, the quick glance at the entire clue list, simple input of rebuses and special characters, the satisfying tactile feeling of filling out a grid by hand—and most of the better benefits of doing puzzles digitally, like clean erasing of mistakes and the ability to store thousands of puzzles in a thin device you can easily bring almost anywhere. It is the perfect crossword device. All for just $340, which is far too many dollars.

The problem is, of course, getting the puzzles onto the device at all. One thing you will have to do is, basically, make your own puzzle packs. Most collected puzzle books don’t have ebook editions (and you cannot write directly on an ebook anyway, remember?), so you will have to track down a lot of PDFs from whatever providers you like. This, so far, is a pain in the ass. If you subscribe to the New York Times crossword, you will have to visit the puzzle section on your computer, go through the archives, and hit print on each puzzle you wish to save as a PDF. If you, as I do, subscribe to AV Club Xwords, you will have an easier time trawling through their archives for PDF links. Then, with either provider, you will likely have to use this Adobe tool to merge all your downloaded individual puzzles into one document, which you will then send to your Kindle by whatever means you usually do such things. (AVXC does also sell bundles of much older puzzles in PDF format.)

The Kindle Scribe is a device that does not seem able to justify its own existence, except as a monopolist’s bulwark against potential competitors in the ebook space that have recently introduced similar products. (I assume the Kobo Elipsa and ReMarkable 2 are equally adept PDF-scribbling machines.) But it is quite good at this one thing that more than justifies its cost, to me, at least, of zero dollars.