For the sake of privacy, no real names have been used in this article.

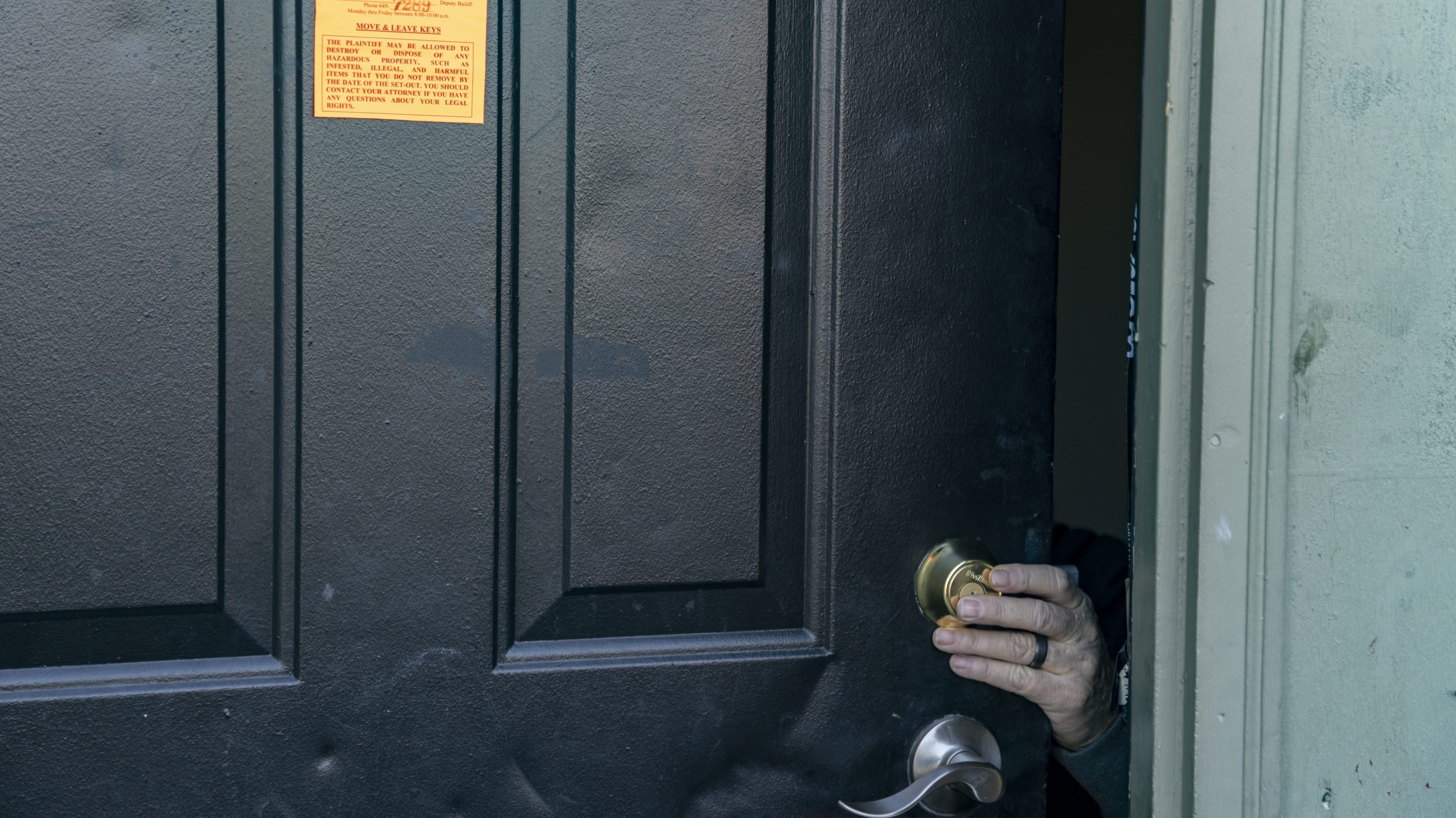

Nothing could have prepared me to watch an elderly woman get evicted in front of dozens of people over Zoom. I’m a legal aid law clerk working to protect tenants, and that means I’ve spent the COVID-19 pandemic witnessing the havoc that an eviction can produce firsthand. Although law clerks are still in law school, we’re often the first people to interview clients, and part of my job involves attending eviction hearings to screen for people who might be eligible for our help. These hearings are heartbreaking, and seeing them unfold online is a surreal experience.

Courts across the country are reopening, but during the pandemic lockdowns I spent more than a year watching landlords try to evict tenants in virtual hearings. These hearings went on, even with a federal eviction moratorium in place, one that is scheduled to end next month.

I’d estimate that in about a quarter of the hearings I watched, the tenants kept freezing or lagging due to poor internet connections. Tenants without reliable internet access had to go to the courthouse in person and wait to argue their case in front of the court’s computer. Every day, poor people who were behind on rent and didn’t have internet access had to attend court in-person, during a pandemic, so they could join a Zoom call and potentially be kicked out of their homes. Many of them didn’t even have a lawyer to help them through the hearing.

If you’ve seen an episode of Law & Order then you know that in the United States, every person accused of a crime has the right to an attorney during their criminal case, even if they can’t afford one. The key phrase there is criminal case. If you can’t afford an attorney for a civil issue, like an eviction, then you’re likely on your own. Having a lawyer on your side changes the entire situation and makes everything easier, even if the lawyer is just there to help you navigate our complicated court system. For people who can’t afford private attorneys, that’s where legal aid organizations can come in and provide free legal service. But we have limited resources and restrictions on our funding, so we can’t help everyone who needs it—and there is a lot of need.

As for the landlords, they almost always have lawyers. Every single landlord has had an attorney at the hearings I’ve attended, and that’s about par for the course nationwide in eviction hearings. And the evictions keep coming. One of the first tenants that I interviewed at my last hearing, Mr. Lopez, was a veteran struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder and other health issues who couldn’t get his landlord to complete basic maintenance in his apartment. Instead of trying to chase down his landlord after making multiple requests for maintenance, Mr. Lopez decided to withhold his rent, a legal remedy available as long as the landlord has been notified of the outstanding issues. Instead of working with Mr. Lopez to make the necessary repairs, as required by law, the landlord instead filed for an eviction almost immediately. Landlords failing to provide repairs is an unfortunately common theme for people who can’t afford to fight back, and Mr. Lopez’s case is still ongoing.

Another tenant, Ms. Smith, had to attend her hearing in person at the court, and she broke down in tears as she relayed her story. Ms. Smith was fortunate enough to be earning at least some of her usual income, but her landlord still tried to evict her after he abandoned his responsibility to maintain her apartment. Ms. Smith and her children were without heat for months in the middle of winter, and her landlord gave her the run-around every time she requested maintenance. Ms. Smith’s pipes were completely clogged, leaving her without running water for months, and she was forced to go to the bathroom in garbage bags and dispose of it when she could. Her children were living part-time with relatives since Ms. Smith wanted to shield them from the severity of the situation—and this is a person who had paid her rent on time, submitted multiple requests for maintenance, and still ended up being the one who got sued.

Or take Ms. Johnson and her children. They moved into their apartment last spring at the dawn of the pandemic. But there were broken electrical outlets everywhere, leaking pipes, rooms that were completely without doors, and no heat. She had asked the landlord to remedy the situation numerous times and to at least provide heat, as required under federal and state law, but all she got was a space heater. After Ms. Johnson made multiple maintenance requests that were ignored, she understandably moved out halfway through the winter. Her landlord immediately sued her for “abandoning” the property. Our office was able to help Ms. Johnson bring a counterclaim against her landlord for failing to provide heat for so long, and her case is slowly moving in the right direction. However, far too many people don’t know that they have the legal high ground when their landlord has all but abandoned them.

Every state and city requires landlords to maintain their properties in compliance with all health, safety, and building codes. In other words, landlords have to keep their apartments in clean, habitable condition. If a landlord refuses or fails to keep their properties in compliance—something that happens far too often for low-income and vulnerable people—then tenants actually have the law on their side. For example, Ohio law gives tenants the right to withhold their rent payments and deposit them with the court if a landlord fails to meet their obligations in a reasonable time (usually less than 30 days) after being notified of an issue. If a court finds that the landlord has indeed failed to meet their obligations, then tenants can reduce their rent until those conditions are satisfied or possibly get out of the lease altogether and avoid paying any more rent. Most states also bar landlords from retaliating against their tenants for requesting maintenance or reporting a landlord’s wrongful actions to a government agency. This retaliation can take the form of illegally increasing rent or shutting off utilities, and tenants can sue for all damages that they’ve suffered from the retaliation.

But most people don’t know that they have these legal protections, and that’s why legal aid is so crucial. Legal aid attorneys and other tenant’s rights attorneys know how to deal with absent landlords, and helping a client deposit rent with the court or file a counterclaim for damages immediately levels the playing field. In response, landlords are more open to negotiation and they’ll often either make the repairs, or agree to drop their claims in exchange for the tenant moving out. Moving out isn’t always ideal for our clients, especially during a pandemic, but sometimes it’s the best option and it avoids saddling someone with an eviction on their record.

One of the weirdest cases involved Mr. Gray, a young tenant who didn’t understand why he was being evicted, as his rent was paid on time and there were no issues to speak of. I assumed it was another example of a landlord evicting someone for no reason, until the landlord showed up and was a complete stranger to Mr. Gray. Turns out, Mr. Gray had made his most recent rent payment to the now-former landlord of his building and he was never notified about making payments to the new landlord. When this was later explained to the new landlord, it turned out that my initial hunch was partially right, as he didn’t care that much about the unpaid rent. He wasn’t interested in explanations or negotiations, he just wanted Mr. Gray out of the building, and the law says that is perfectly alright. Meanwhile, Mr. Gray will likely never get his rent money back from his former landlord, and he had to find a new place in the middle of COVID-19.

It might be surprising to hear that evictions were going forward at all during the pandemic, seeing as an eviction moratorium was implemented in March 2020, and has been extended several times since. The moratorium managed to stay in place at the national level, but this type of relief has always evaded poor people in this country. You would think someone being evicted could just tell the judge about their situation and go back home, but the moratorium came with several hoops to jump through for tenants. Tenants seeking relief have to meet all of the qualifications, some of which are fairly subjective, like convincing a judge that they’ve done everything possible to get all available government rental assistance. Tenants also must prove that they’ve made their best efforts to pay their landlord, despite their financial position, and they have to show that an eviction would make them homeless or force them to live in “close quarters” with other people.

Because landlords can terminate these leases on a whim, this means untold numbers of people are being evicted during COVID-19 simply because the landlord wants someone else in that unit, and this has happened at each hearing I’ve attended. No late rent payments, no noise complaints, no damage to the apartment unit, no utilities issues. The landlord just wants them gone for whatever reason, and it gets even more brutal when you realize that most of the people in these hearings are on rental assistance programs, guaranteeing that the landlord receives rent payments each month. It’s guaranteed income! But because of the stigma of rental assistance, or because the landlord just wants to bring in tenants who can pay higher rents, something compels certain landlords to kick out poor people as soon as possible, especially when they take over a new building. And all this is about to become much easier to do going forward, because the federal evictions moratorium expires on July 31. In its announcement, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said "this is intended to be the final extension of the moratorium."

The moratorium was only a temporary fix for a long-term problem. There are supposed to be protections in place that prevent landlords from evicting people due to unpaid rent that accumulated during the pandemic, but the fact that landlords have been successfully evicting people this whole time, regardless of their situations, tells you how much that protection is really worth. Some judges are even disregarding the moratorium completely, just because they personally disagree with it, and are instead issuing unlawful evictions on behalf of huge rental companies. Even for those fortunate enough to avoid an eviction, the overdue rent keeps piling up, which can impact a tenant’s ability to rent another place in the future. Instead of designating funds to fully subsidize rent payments, or to pay landlords directly, millions of people who have fallen into poverty were provided with Band-Aid solutions. The pandemic and the insurrection and the infinite attempts at overturning the election have only laid bare a system that has never worked for millions of people and has always left them on the margins.

So that’s how we ended up in a world where I watched an elderly woman get evicted for literally no reason, and that’s perfectly allowed. In most of the country, state law allows landlords to end a month-to-month lease for any reason, or no reason at all, as long as it’s not openly discriminatory, which is what happened in her case. From my experience, a disproportionate amount of people with monthly leases are already low-income or otherwise vulnerable, and they often rely on these types of leases precisely because it can be harder to qualify for long-term agreements. While monthly leases might provide some flexibility for tenants, they come with fewer protections when a landlord wants you gone.

I couldn’t tell you the worst part of an eviction hearing; it’s all bad, but I absolutely can pick out the worst part of the eviction crisis, and the pandemic, and the economic crisis: That’s the fact that it didn’t have to be like this. This is what happens when a society embraces a system where it’s somehow more profitable to have unoccupied luxury apartments than affordable housing for everyone, where homeless people are sleeping in designated parking spaces while nearby hotels sit empty. Where an entire state crumbles under an unprecedented snowstorm because their leaders refused to take the appropriate steps following the last unprecedented snowstorm.

This is what happens when, despite the fact that stimulus payments objectively reduced hardships during the pandemic, politicians negotiate against themselves to make sure fewer people receive future payments instead of wielding their power to help people stay safe and simultaneously stimulate the economy. And of course, some of the biggest landlord companies have seen record-breaking profits during the pandemic while millions of people are about to face eviction hearings once the moratorium ends. It doesn’t have to be this way, but millions of us are just going from one disaster to the next. Why should our housing policy be any different?

Additional Info:

If you’re facing an eviction or another civil legal issue, please contact your local legal aid organization for help. Even if you don’t qualify financially, they can hopefully still point you in the right direction, and sometimes that makes all the difference.

To find your nearest legal aid organization, click here.

If you are behind on rent or facing a potential eviction, you might also qualify for rental assistance in your city. Click here to find additional help.